I Have A Dream

A young Dodge designer’s take on the Challenger and Dart—take it or leave it.

By Cliff Gromer Photos and illustrations from the Herb Grasse Archives

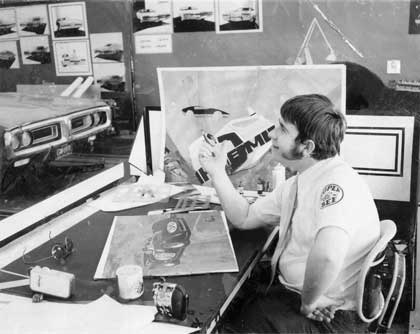

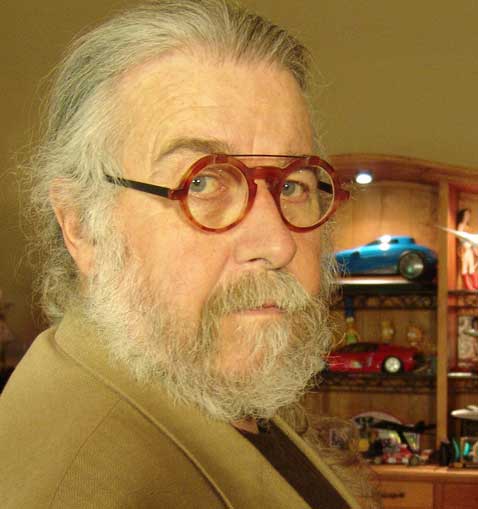

You know how it is. A guy gets out of design school, lands his first job with a car company and thinks he’s going to change the look of transportation on the planet. That’s what Herb Grasse thought when he went to work in the Dodge design studio in mid ’68, a job that was to last one year before Herb moved on to Ford where he figured the grasse would be greener.

But instead of redesigning the Dodge lineup top to bottom and being hailed as a visionary genius, Herb, at the very bottom of the design food chain, was delegated the menial task of designing scoops and stripes. Sort of like the equivalent of a dishwasher in a restaurant. Still, Herb, like all designers have dreams, otherwise they wouldn’t be designers, instead ending up as something more like magazine writers.

When Herb came aboard at Dodge, the 1970 Challenger and Dart already was in stone, and the studio were tweaking the ’71 and ’72 models—basically grille and taillight themes, and exploring new ideas for these models down the road. These concepts were referred to as 70X.

The chief designer at Dodge was Elwood Engel, and Herb’s immediate boss was senior designer, Geoff Godshall. The designers would draw their concepts which would be displayed on a wall. Engel, who had pitched baseball sometime back, would select his choice of the designs to go into clay models by taking a hot clay ball and hurling it, from across the room, at his choice on the wall. The designs with the big stains on them were the winners.

The clay model was actually two designs in one, the left side differing from the right. So two semi-finalists could be evaluated on one model—a cost-savings measure. The winning side was then carried over to the opposite side to make the model symmetrical—a process called “flopping the winner.” Engineering would take their points off the clay model in 5-inch grids..

When prototype models were produced, they were put on a turntable for view by corporate brass. The turntable became just a table after Engel decided to chirp the tires when driving a Hemicar off the turntable. He didn’t realize that only one of the rear wheels was on the table, the other was on the floor.

Back when Ford was making a lot of noise with their “Grabber” models, and they used catchy names for their car colors, such as “Grabber Orange,” Chrysler’s marketing guys came to Styling, and asked them to come up with some cool names for Dodge and Plymouth’s high impact colors. Why not? Taking a page from Ford, Styling called their flashy red color “Grabber Cherry.” Other brainstorms included “Medi Ochre,” “Come And Get Me Copper,” “Gold Digger,” “Statutory Grape,” and the real winner of the bunch—“Lemon Yellow.” Needless to say, marketing never requested Styling’s input on paint colors ever again.

Some of the designers in the studio had their own pet projects they were noodling around. Bruce Hatch, for example, was trying to come up with a one-man dirigible based on a helium-filled balloon with twin props so he could fly to work and beat the traffic. It never got off the drawing board, let alone the ground.

Herb took his scoop assignments over the top with a design that had latex “gills” on the top. Working with vacuum actuators, the gills would open and close on acceleration giving the impression that the scoop was “breathing.” Herb thought this would really be cool. No one else did.

When Herb tried to “borrow” some clay from the studio for an outside project he was working on, he figured he would have a hard time getting the 10 lb. clay bricks past the security guards. The design studio was on the third floor of the old Hamtramck building and the windows opened outward. So Herb parked a pickup truck under the window and figured he’d just toss some clay bricks into the bed. There was a guard shack close by, and when Herb tossed the clay, the wind caught it and carried it over to the corrugated metal roof of the guard shack. The noise was spectacular, and the guard ran out with his head vibrating like a character in a Looney tunes cartoon. Herb explained that the brick fell out the window “by accident.”

The highlight of Herb’s short career at Dodge was a chance to work on the Yellow Jacket factory show car. Herb and Geoff Godshall provided input on the car that was being built by Ron Mondrush, at Synthetex Fabrication. The Yellow Jacket subsequently was redone as the Diamante, and became part of the late Steven Juliano’s awesome collection.

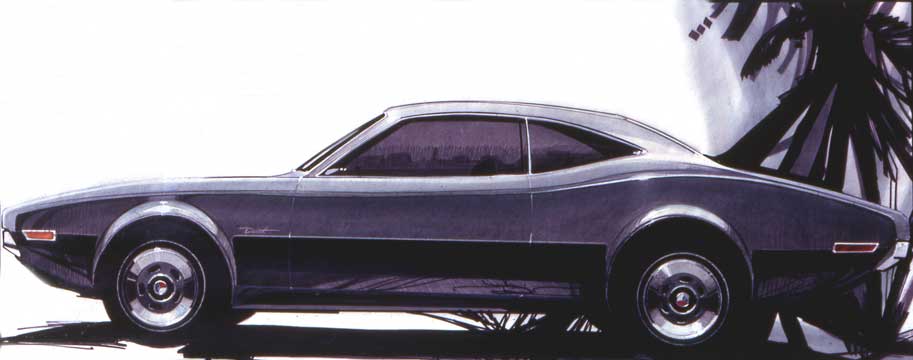

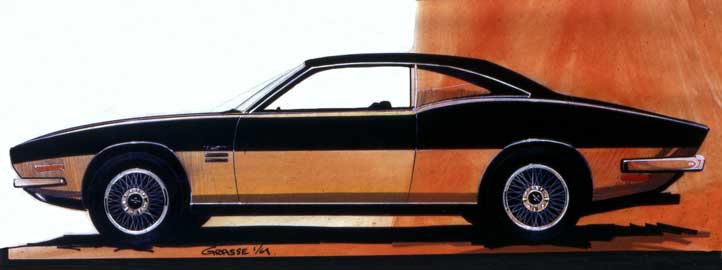

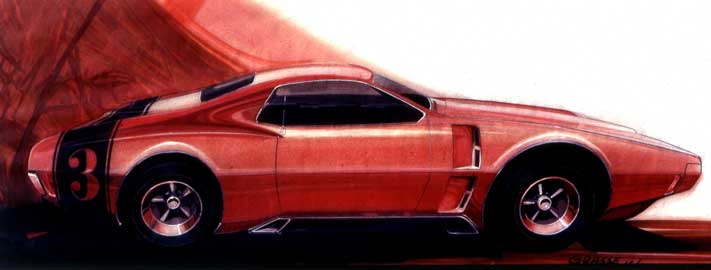

’s Barracuda. The Challenger here gets a heavy aero makeover. Herb was a fan of sidepipes (as used on the Corvette and later, the Viper), and he added them in this illustration.

Herb’s vision for the Challenger and Dodge Dart took a different tack from that of the factory, with Herb favoring more of a Euro/GT/sports car approach than a muscle image. The illustrations shown here were spirited out of the design studio under Herb’s trench coat, which he wore religiously, even though it hadn’t rained in two weeks, and the outside temperature at times climbed to 80 degrees.

Leaving Dodge, Herb went on to work at Ford. After that, he basically single-handedly designed the ill-fated Bricklin—the original pool car as it leaked like a sieve when it rained.