Chrysler’s Stock Car Connection–Part 4

The Daytona Firecracker 400, NASCAR’s bombshell and the end of an era.

By Wm. R. LaDow Photos from the Nichels Collection and the Nichels Engineering Archives

THE STORY SO FAR

Part 1: GM bows out of NASCAR, opening the door for F.R. Householder, Chrysler’s Manager—Circuit High Performance Competition, to sign on Nichels’ Engineering, which formerly fielded race-winning Pontiacs, to become Chrysler’s stock car builder. Part 2: Nichels debuts his 1963 Plymouths. Initial testing and competition prove out Nichels designs. USAC drops a bomb. Part 3: The Hemi debuts and sends shockwaves through the racing world.

A.J. Foyt on his way to winning the 1964 Firecracker 400 at Daytona in his Nichels Engineering Hemi-powered Dodge.

The 1964 Firecracker 400 had all the ingredients for a race like no other. Five months prior, Nichels and his Chrysler contingent had come to Daytona and dominated speed weeks. Since that time every race team running either Plymouths or Dodges had up to some 30 NASCAR races to get a better handle on how best to marry the brute Hemi power to the newly designed unibody constructed sedans. It was no small challenge. It was becoming clear to those in the know, that tire technology was not keeping with up the advancements in engine and body design. The cars were now going frightfully fast and keeping them on the race track was becoming even more of a tremendous chore.

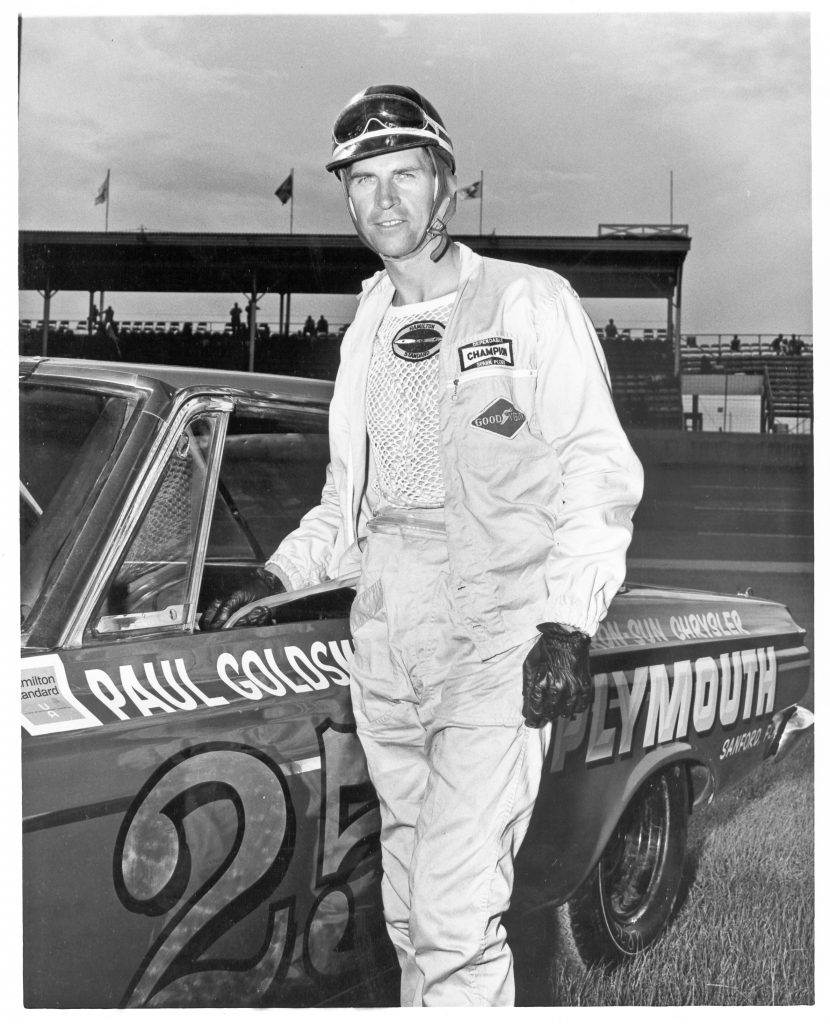

The weather on this Independence Day weekend was hot, terribly hot. Goldsmith took the opportunity to debut a product he had been working on with a firm, the Hamilton Standard Division of the United Aircraft Corporation. It was an air-conditioned driving suit. The suit had been initially designed for NASA’s Apollo space program by a couple of companies, the most notably being Goodyear Tire and Rubber. The suit was made of a mesh garment that had liquid-filled tubing sewn to the fabric. The suit’s liquid coolant was held in “cold box” located behind the driver’s seat and the suit’s pump powered by car’s battery. The benefit of its use was two-fold, first was to relieve driver fatigue, the second was additional protection against fire. Paul had been working with the idea for some time and was intent on using it in the upcoming 400 mile race.

Thursday, July 2, 1964 was the end of an era in American stock car racing. That morning at a little after 7:30 am, Glenn “Fireball” Roberts died of the injuries he sustained over a month before on May 24th in the World 600 at Charlotte. His valiant struggle for life kept many spirits high during his five week ordeal. But only those closest to him knew that the last two weeks he had slowly been losing his battle. The entire racing community felt as if it had lost a family member. When the news hit the garages at the track, there was a collective emptiness felt by all. Bill France addressed the media telling them how much Roberts would be missed, but that racing would go on, just as Glenn would have wanted it.

During the next two days NASCAR conducted practice, qualifying and a couple of qualifying races at the track. There was some good news. A.J. Foyt, who had been driving stock cars built by Ford during the first half of the year, announced he was leaving their employ. Foyt was particularly unhappy that Ford failed to provide him a rear-engine Lotus-Ford for the previous Indianapolis 500, a race he eventually won in a traditional roadster. One phone call later, Anthony Joseph Foyt found himself the chauffeur of a brand new Nichels Engineering Dodge Hemi-Polara. Ray Nichels was now going to field Goldsmith in the No. 25, Isaac in the No. 26 and A.J. in the No. 47. The bad news was during the course of the one of the two 50-mile qualifying races on Friday, Goldsmith, while leading, put his Plymouth into a spin. Just as Goldy was gaining control, Fred Lorenzen slammed into Paul destroying both cars. Goldsmith came out of the wreck unhurt, while Lorenzen was taken to the hospital with a badly cut tendon in his left wrist. Both drivers were now without cars for the race the next day. Foyt almost got gathered up in the wreck, but escaped without his car being totally destroyed. The Nichels team worked all through the night repairing the No. 47 Polara so it would ready to run in time for the 400 miler.

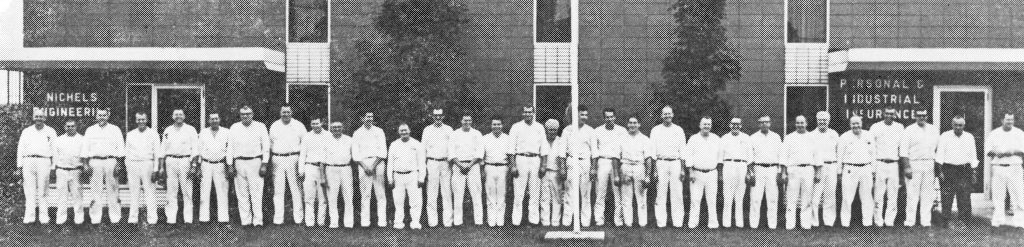

The mechanical and engineering staff outside of the newly-construction Nichels Engineering “Go-Fast Factory.”

Race day, July 4th, was unbearably hot with temperatures in the 90s. Temperatures within the cars prior to the race were estimated at 140 degrees. Goldsmith not needing his hi-tech “cool suit” gave it to Bobby Isaac to use during the 140 lap race. With almost 35,000 fans watching, pole sitter Darel Dieringer, in a Bud Moore Mercury, led the field to the green flag. Isaac started in the second row, in the fourth position. His new teammate Foyt started all the way back in 19th. No matter, after 25 laps Foyt was running with the leaders.

The day’s racing was brutal. Drivers began asking for relief by mid-race. Five caution flags (totaling 25 laps) didn’t slow the pace much as the longest yellow was only 8 laps following a wreck on the 103rd circuit around the two and half mile superspeedway. It was then the race’s outcome began to take shape. Richard Petty, the race leader, lost his engine on the 103rd lap. The two speedsters directly behind Petty were in Nichels’ cars. Isaac was leading when he pitted for gas on the 106th lap, surrendering the lead to Foyt. Once Isaac was back on the track he chased down Foyt and beginning with lap 110 the Nichels’ drivers put on an old-fashioned trophy dash. The lap after lap battle continued for 50 trips around the massive high-banked track. The Nichels pilots exchanged the lead over and over. In back of them were two other Nichels built cars belonging to Jimmy Pardue in the No. 54 Plymouth and Buck Baker in the No. 3 Ray Fox prepped Dodge. Isaac continued to run flat-out with Foyt in his draft. A.J. took every opportunity to “measure up” the best place to make the last lap pass he knew he would need. On the sidelines Ray Nichels was beside himself. His Chrysler Corporation delegation had seven cars in the top ten, with the leaders pushing each other like there was no tomorrow. Isaac and Foyt exchanged the lead 15 times over the last 55 laps. Every fan in the place was on their feet, when Bobby Isaac pushed past Foyt going into the white flag lap. Foyt drafted Isaac hard coming out of two and pushed his Nichels Dodge for all it had, inching past Bobby at the end of the backstretch. As they went into three Isaac had to go high and like the great racer he had become, held his line. As they came around the fourth turn, Foyt attempted to run away with the victory, but Isaac would have none of it. Bobby pointed his Nichels Polara at the finish line and gave it all he had. But Bobby, running side-by-side with Foyt, ran out of real estate, finishing just three feet behind his teammate.

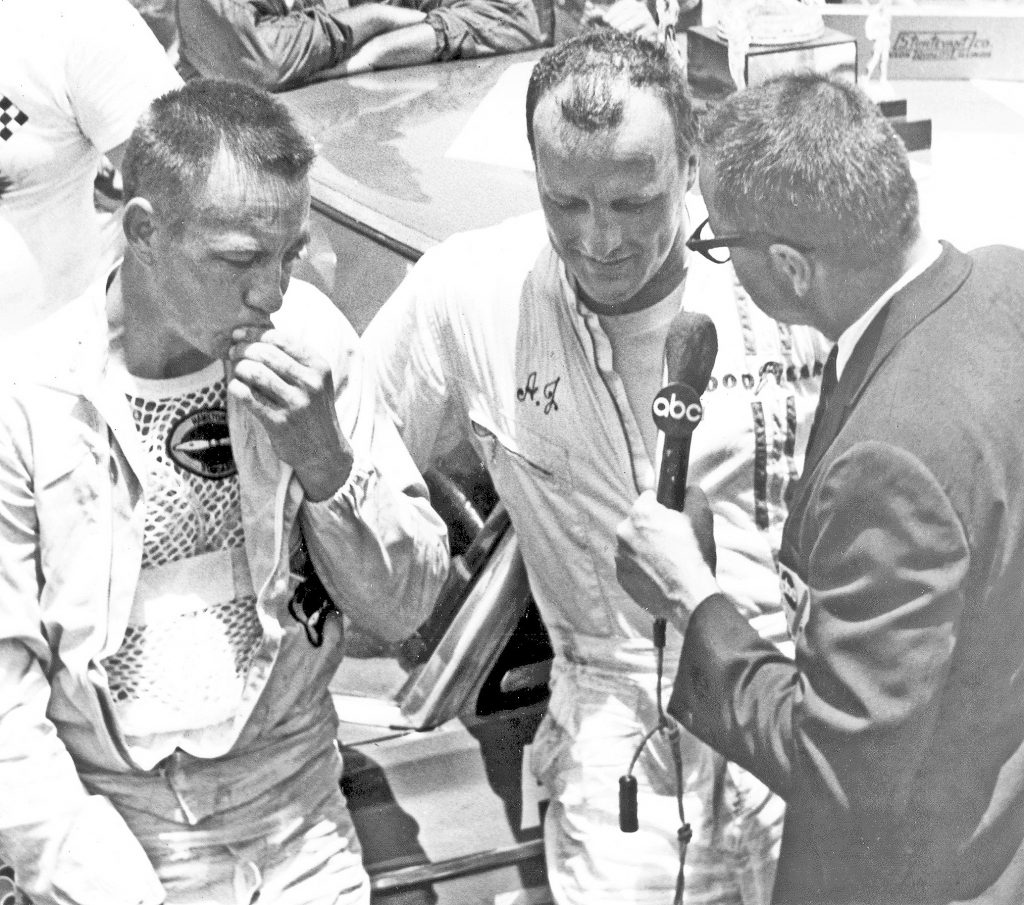

Both cars headed to Victory Lane as Isaac believed he too may have won the race. Isaac would say later, “All I needed was 30 more feet.” Foyt didn’t disagree. As Chris Economaki conducted the interviews with Foyt and Isaac side-by-side, those around him couldn’t help but notice that A.J.’s racing uniform was soaked with perspiration. In the meantime, Isaac stood there nice and dry, a testament to the suit that kept him cool during the Daytona battle.

When the day’s final statistics were tallied, Chrysler had seven of the top 10 finishers. Goldsmith even got into the act relieving Jim Paschal in the Petty Enterprises No. 41 Plymouth on the 83rd lap. The race was run at a record pace of 151.451 miles per hour and it was an absolutely stellar performance.

A.J. Foyt, four-time national champion, two-time Indianapolis 500 winner, was now a first-time NASCAR winner at Daytona. Many who watched the 55 lap see-saw battle were convinced they had just witnessed the greatest stock car race ever. Many too were convinced that they just might have watched one of the greatest drivers ever in the history of American auto racing in the person of A.J. Foyt. In time, Young Isaac would have further opportunities to prove just how good he was too.

The winning 1964 Daytona Firecracker 400 Nichels Engineering stock car team.

From left: Red Owens, A.J. Foyt, Ralph Knopf, Bob Kammer, Minnie Joyce and Bill Delaney. This team also supported 2nd place Nichels Engineering finisher Bobby Isaac.

The Nichels Engineering team, still grieving over the loss of their own Tiny Worley, had come to Daytona and conquered it. Now, as the afternoon turned to evening, they headed to the Baggett-McIntosh Funeral Home to pay their respects to the family of Glenn Roberts. They knew about sorrow and knew that being among friends was one of the things that helped them overcome that sorrow. The next day at 4 PM at the First Baptist Church in Daytona Beach, Ray Nichels, Paul Goldsmith and hundreds of others attended Roberts’ funeral. Later the funeral procession took them all to Glenn’s resting place in Bellevue Memorial Park, just about a mile away from the Daytona International Speedway, an appropriate spot for one of NASCAR’s greatest racers.

Once finished at Daytona, the Nichels team began to put their schedule together for the second half the USAC and NASCAR seasons. Goldsmith and Isaac would continue to run in NASCAR, but now Foyt would join Len Sutton and rookie Joe Leonard in USAC. The schedule didn’t give Nichels Engineering much time regroup.

The Nichels teams would again have to go in two different directions. A USAC 200-miler in Milwaukee on July 12th, would occupy the efforts of Foyt, Sutton and Leonard. While those three cars were busy in the Midwest, Goldsmith and Isaac had back-to-back NASCAR races on the New York road courses at Bridgehampton and Watkins Glen.

On September 3rd, in the midst of the NASCAR and USAC racing schedules, Ray Nichels and Nichels Engineering issued a formal announcement to the press. Ray publicly announced that he had recently closed a transaction with the Keen Foundry Company, located in Griffith, Indiana to purchase 10 acres of land at the corners of Colfax and Main Streets. Upon this property, Nichels Engineering would construct a new, state-of-the-art, 40,000 square foot automotive engineering, testing and research facility. Nichels employees didn’t call it a facility. They had a much more accurate label for their new 40,000 square feet place of employment. They called it the … “Go-Fast Factory.”

Just days after announcement, the Nichels team headed to Darlington for the September 7th Southern 500, one of NASCAR’s biggest races of the year. Goldsmith’s and Isaac’s qualifying efforts placed them side by side in the fifth row. Their effort proved to be just a small part of a crash-plagued race day. Goldsmith ran with the leaders a good part of the afternoon before a vibration took him out of the race after 129 laps. Isaac was able to compete a bit longer going 176 laps before an axle broke. Overall though, it was great day for Chrysler. Buck Baker driving the Nichels built, Ray Fox prepped No. 3 Dodge, won his third Southern 500. Only 14 cars finished the race and of the top-five, four were Chryslers, with Baker being followed across the finish line by Chrysler teammates, Jim Paschal, Richard Petty and Jimmy Pardue. Ned Jarrett in the No. 11 Bondy Long Ford was the only non-Mopar able to crack the top five.

The next stop for the USAC speedsters was the famed Indiana State Fairground’s dirt oval for the 100 mile “State Fair Century.”

Paul Goldsmith at Daytona for the Firecracker 400, in his newly engineered Hamilton Standard “Cool Suit.”

The evening of racing on September 9th had a late start due to the sloppiness of the wet track. Drivers were informed that in an effort to save time, they would only get to take one lap to qualify. Veteran Len Sutton was the first out in his Nichels Dodge Hemi-Polara. In a mental lapse uncommon for Sutton, he failed to warm up his brakes during the practice lap. When he got the green flag for his qualifying attempt, he drove his Nichels mount hard and deep in the first turn, but when he hit the brakes – nothing! Len slid clear up to the outside guard rail, bounced off of it and attempted to continue his run. It was just enough to take at least a full second off his time and by the end of qualifying it appeared he missed the show.

Then A.J. Foyt put his Nichels Dodge Polara through its warm-up. He flashed the OK sign as he went by Nichels’ pit crew and slammed his right foot down. His Dodge’s Hemi roared to life for an instant, then nothing. Moments later A. J. rolled into the pits with a blown engine and no time to put in another. Foyt exited his car and ran down Nichels voicing his unhappiness with the engine failure, stating, “From now on, no one, I mean no one, works on my engines but Minnie Joyce.” Foyt was sharing his opinion that someone other the Nichels Engineering chief engine builder must have worked on his car and as result the Hemi wasn’t up to snuff. Ray Nichels nodded, understanding Foyt’s frustration.

Bobby Isaac and A.J. Foyt explain to Chris Economaki how they ran fender to fender for 50 laps until a last lap pass by Foyt, to bring both Nichels Engineering cars to a 1-2 finish in the Firecracker 400 at Daytona.

A.J. then disappeared into the paddock area where the Nichels’ Dodges were parked. In the meantime, Joe Leonard qualified with the second-fastest time and earned a spot on the outside of the front row next to pole sitter Bobby Marshman.

With qualifying keeping everyone’s attention, Foyt quietly grabbed a couple wrenches and went to work at swapping the doors of his and Sutton’s cars, hoping to qualify Sutton’s Dodge as his own. It didn’t take long for the word to spread though, and before long USAC official Henry Banks caught A. J. like a boy with his hand in the cookie jar, telling Foyt to cease and desist. Foyt wasn’t finished just yet. He sprinted off to the judges’ stand, cornered several officials, and as Region writer Gary Galloway reported, “The air turned blue.” Minutes later A.J. strolled back to his pit, his white teeth flashing in a wide grin. “Get Sutton’s car ready,” he told Nichels. “I’m driving it!” The PA system confirmed what A.J. had just said. “In the interest of a better show,” the announcer said, “the field is being increased to 30 cars . . . A. J. will drive teammate Len Sutton’s car No. 29.” Foyt’s position was simple; he was being paid an appearance fee. Many of the fans clearly were there to see him race. If USAC wanted him to go home, that was fine with Foyt. He just needed his appearance fee payment and he’d be gone. USAC couldn’t disagree with A.J.’s logic.

USAC officials put A. J. dead last in the field. He blew-off nine cars on the first lap. At the end of 25 rounds of the 100-lap race on the State Fairgrounds dirt mile, he was running fifth. He gobbled up his Nichels teammate Leonard next, and then took off after the Ford entries of Don White and Marshman. He went high, cut low into the corners and whipped onto the backstretch with just one more car to left to catch … Parnelli Jones in the Stroppe Mercury Marauder. A. J. was standing on it. He stuck his front bumper in Parnelli’s trunk and around and around they sped, just inches apart. They stayed that way until the 60th lap when Jones blasted through the third turn fence. Official word had it that his brakes went out. But some will always believe A. J.’s torrid pace pressured him right out of the track. It was a breeze the rest of the way. Winning was anti-climatic and so was Foyt’s record speed of 75 mph. The fans left the track night seeing a race that they would likely never forget. Gary Galloway, an award-winning writer, later labeled the event as “A Race to Remember” and he couldn’t have been more correct.

Nichels Engineering’s 1st and 2nd place finish in the Daytona Firecracker 400 sparked the imagination of many of Ray’s sponsors.

As both the Nichels USAC and NASCAR teams were getting ready to close out the season over the next six weeks, terrible news came out of Charlotte. On September 22nd, Jimmy Pardue in his Nichels Engineering built Burton-Robinson Plymouth was conducting tire tests (featuring inner liners) for Goodyear at the Charlotte Motor Speedway, when a tire came apart going into the third turn. Pardue’s Plymouth struck the metal highway-type guardrail and blasted through it, going down over the embankment, coming to rest near the entrance of the tunnel leading to the infield. Less than four hours later, while in the Cabarrus Memorial Hospital outside Charlotte, Jimmy Pardue was lost forever. He was one of the best hires Ray Nichels was a part of. In 1964, driving Nichels Engineering cars exclusively, Pardue participated in 50 Grand National races, gaining 2 poles, 14 top fives and 24 top-ten finishes winning $41,597. His season ranking was 5th overall; an incredible effort considering he sadly lost his life almost two months before the end of the NASCAR season. Jimmy Pardue had been on the brink of stardom

Then while the Nichels teams were trying to wrap up the season and start their planning for the upcoming 1965 schedule, NASCAR dropped a bombshell.

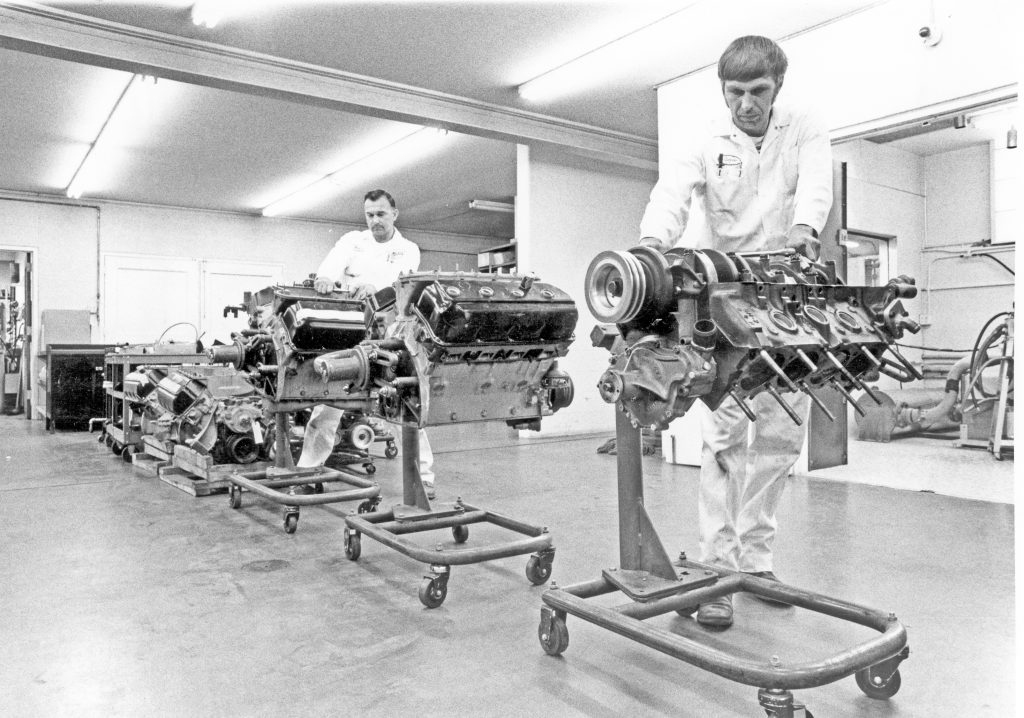

Jerry Govert (L) and Tope Phillips (R) working Hemi engines in the motor room at the Nichels Engineering “Go-Fast Factory.”

During the course of the 1964 season, it became obvious to all involved that the racing speeds were getting too high. Everyone was beginning to come to an agreement on that subject. The problem was how to deal with it. NASCAR had lost three of its stars in the 1964 season; it didn’t want to lose any more. For several months, NASCAR President Bill France sought to find a solution that would keep the drivers, owners and the factory sponsors content with their individual racing investments, yet reduce speeds.

On October 19, 1964, NASCAR announced a new series of rules for the 1965 season. New specifications designed to slow down the big Grand National cars and provide additional safety measures, took aim at the “limited production” engines. General rules for the 1965 NASCAR Grand National season were issued as follows:

1. Engine maximum size — 428 cubic inches of production design.

2. Elimination of certain engines — Hemispherical combustion chamber and hi-rise cylinder heads, roller cams and roller tappets.

3. Wheelbase — 119 inches on superspeedways and 116 inches on short tracks and road courses.

4. Carburetor — One 4-barrel carburetor, 1- 11/16 inch opening for each venturi.

5. Rubber lined gas tanks — Fuel cells, currently under scrutiny by NASCAR, may be made mandatory if they pass safety testing. (Author’s note: This particular regulation was directly related to Glenn Roberts fatal accident in the Charlotte 600. Both Firestone and Goodyear became increasingly active in finding a “rubber lined fuel cell” solution for fuel related fires.)

The new NASCAR rules, effective January 1, 1965, made Chrysler’s hemispherical cylinder head (HEMI) engine illegal. It also appeared that it would put Nichels Engineering out of the racing business in NASCAR.

Once again, by the stroke of a corporate pen, Ray Nichels’ entire racing enterprise, including his new 40,000 square foot building currently under construction, was in jeopardy.