Chrysler’s Stock Car Connection–Part 5

NASCAR bans the Hemi, so Chrysler waves goodbye and turns to other race sanctioning bodies.

By Wm. LaDow Photos from “Conversations with a Winner – The Ray Nichels Story.”

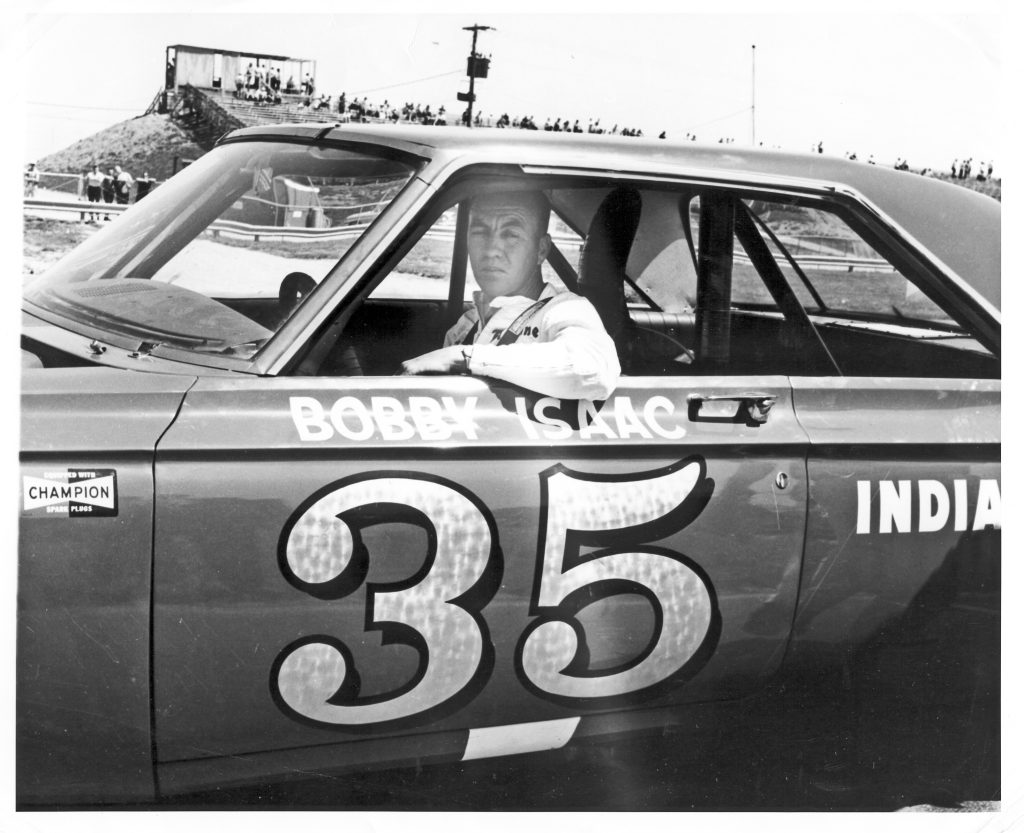

Nichels driver Bobby Isaac racing USAC at the Milwaukee Mile during Chrysler’s early 1965 boycott of NASCAR.

Â

The new regulations issued by NASCAR regarding engine type and size, along with a new wheelbase directive, put some racing competitors in a quandary about how to prepare for the 1965 racing schedule. In the case of the Ford Motor Company, they were little impacted by Bill France’s announcement. Ford could continue to race without giving up much in the way of engine size or horsepower. General Motors had not been a factor in NASCAR racing since their exiting the sport in 1963, though there were a few loyal independents still running the equipment. The automaker most penalized by these new regulations was clearly Chrysler Corporation, with both the Plymouth and Dodge divisions paying the ultimate price. Following Bill France’s announcement on October 19th, Chrysler Corporation executives held a series of meetings to study the ramifications of the NASCAR mandate. They made their decision quickly and agreed that Chrysler should speak with one voice. That voice belonged to Ronney Householder.

On Friday, October 29, 1964, ten days after Bill France’s initial rules announcement, Ronney Householder issued the following prepared statement on behalf of Chrysler Corporation.

“The 1964 stock car season attracted the largest crowds and paid the biggest purses in history. The season has been a credit to all who participated. Plymouth and Dodge cars with the 426 cubic inch Hemi engines and their drivers gave a good account of themselves in all sanctioned competitive events and contributed greatly to the season’s success.

“The standard practice of all competitive sanctioning bodies is to make major rule changes after thorough discussion with owners, drivers, track owners and equipment manufacturers; and to provide a minimum of one full year’s notice prior to adoption. The new NASCAR rules for the 1965 season as announced on October 19, 1964, do not permit an orderly development and testing program for replacement of equipment already programmed. The new rules interrupt the continuity of engineering cars for safety and performance and they are not consistent with racing’s tradition of bringing the best and newest engineering equipment to the race track. We also believe the rules will work to the disadvantage of many car owners, some drivers, crews and track owners. The effect of the new NASCAR rules will be to arbitrarily eliminate from NASCAR competition the finest performance cars on the 1964 circuit, including the car of the Grand National champion. Under these new rules, the equipment running on NASCAR tracks in 1965 will be inferior to the best the automotive industry can produce for this purpose.

Paul Goldsmith in the #36 Plymouth Belvedere leads Norm Nelson driver Jim Hurtubise around the turn at DuQuoin, Illinois. Goldy on his way to one of his 4 wins and 2nd place overall in USAC competition in 1965

Â

“Accordingly, unless NASCAR rules for 1965 are modified or suspended for a minimum of 12 months to permit an orderly transition to new equipment, we have no alternative but to withdraw from NASCAR sanctioned events and concentrate our efforts in USAC, IMCA, NHRA, SCCA and other sanctioning bodies in 1965. In any case, the outstanding Dodge and Plymouth Hemi-head cars will be racing wherever track owners want the public to see championship performances by stock car equipment.

Householder’s points were clear and concise. Unless the new regulations were revised or rescinded, Chrysler would not participate in NASCAR racing in 1965.

Bill France was not pleased. He ruled NASCAR with an iron hand. On this particular issue he was driven by a noble cause, safety. France did not want to continue to see any more great drivers (and great friends) lose their lives. Unfortunately, his zeal to curtail the speeds had multi-million dollar implications for people like Ronney Householder and Ray Nichels who were trying to run their respective businesses. Everyone was in agreement that the speeds had to be reduced. But one side of the equation, the automaker side, wanted at least a “fair” amount of time to phase in the changes. France wasn’t interested in compromise. He was willing to take a gamble that Chrysler couldn’t stay away from racing. France was also hoping his effort might entice General Motors to return to NASCAR to challenge Ford. Time would tell.

The discussion about the safety of speed, took another turn for the worse on January 9th when Bud Moore’s promising young driver, Billy Wade, was killed during tire testing at the Daytona. Wade, a father of four, had recently moved to Spartanburg, South Carolina, to be close to his car owner Moore’s shop. It was another terrible loss for racing.

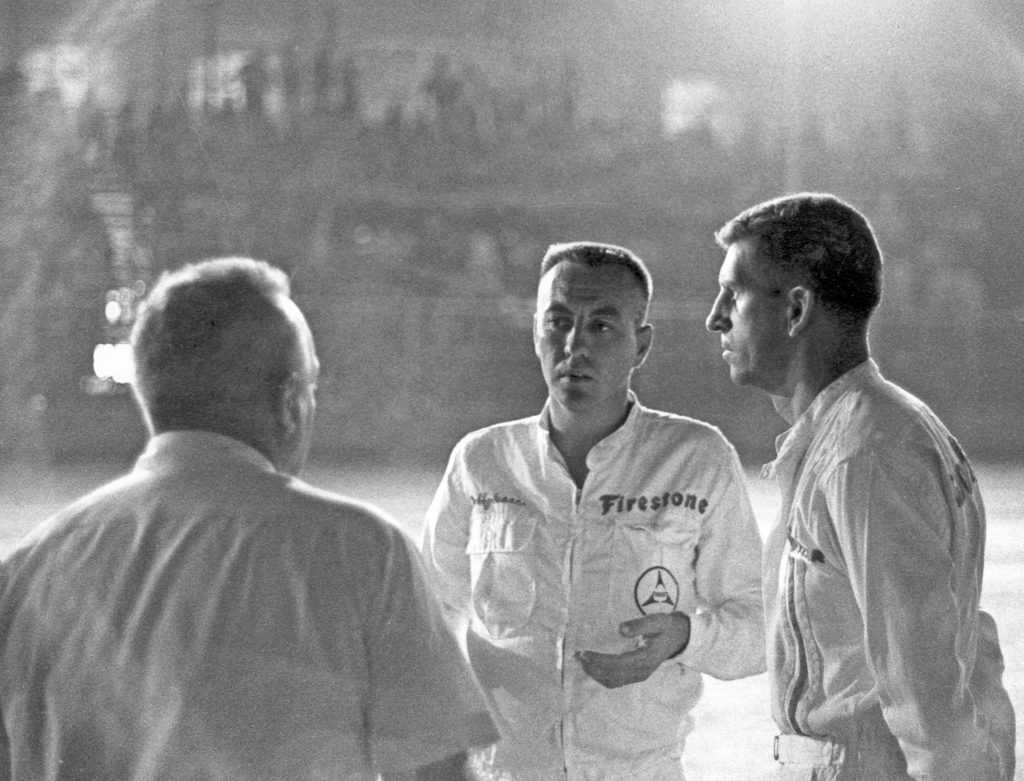

Ray Nichels (left), Bobby Isaac (center) and Paul Goldsmith at the 100-mile USAC race at the Indianapolis Fairgrounds on September 7, 1965. Isaac raced USAC part of the 1965 season due to the Chrysler boycott of NASCAR’s decision to ban the 426 Hemi engine. Isaac won 2 races prior to leaving USAC and returning to NASCAR.

Then to top that off, Jimmy Pardue’s replacement driver, 28 year-old Larry Thomas was killed in a highway accident in Tifton, Georgia on the way to Daytona. Thomas’ loss was the final blow for the Burton-Robinson Plymouth race team that had performed so well in 1964. They folded their operations and never raced again.

In the case of Ronney Householder and Ray Nichels, it meant sweeping changes in a manner of weeks to prepare for a transition to USAC stock car racing full-time. It also meant more of an emphasis on IMCA and ARCA, the other two prominent stock sanctioning bodies in American racing. For Nichels Engineering, it meant a complete realignment of the driving duties and an emphasis on finding the most efficient plan to run the racing business out of the Highland shop while the new Griffith facility was being constructed. Nichels knew that with Chrysler dropping out of NASCAR, his car building and replacement parts business was going to suffer tremendously, and at the very same time Ray was making a huge outlay of capital for the construction of the new Main Street shop in Griffith. Cash flow could be managed, but it would have to be scrutinized closely. The plans for hiring more employees would also be put on hold.

Nichels’ next task what to make driving assignments for the upcoming season. Goldsmith had been suspended by USAC (United States Auto Club) at the end of 1963, and as a result he had driven exclusively in NASCAR for the 1964 season.

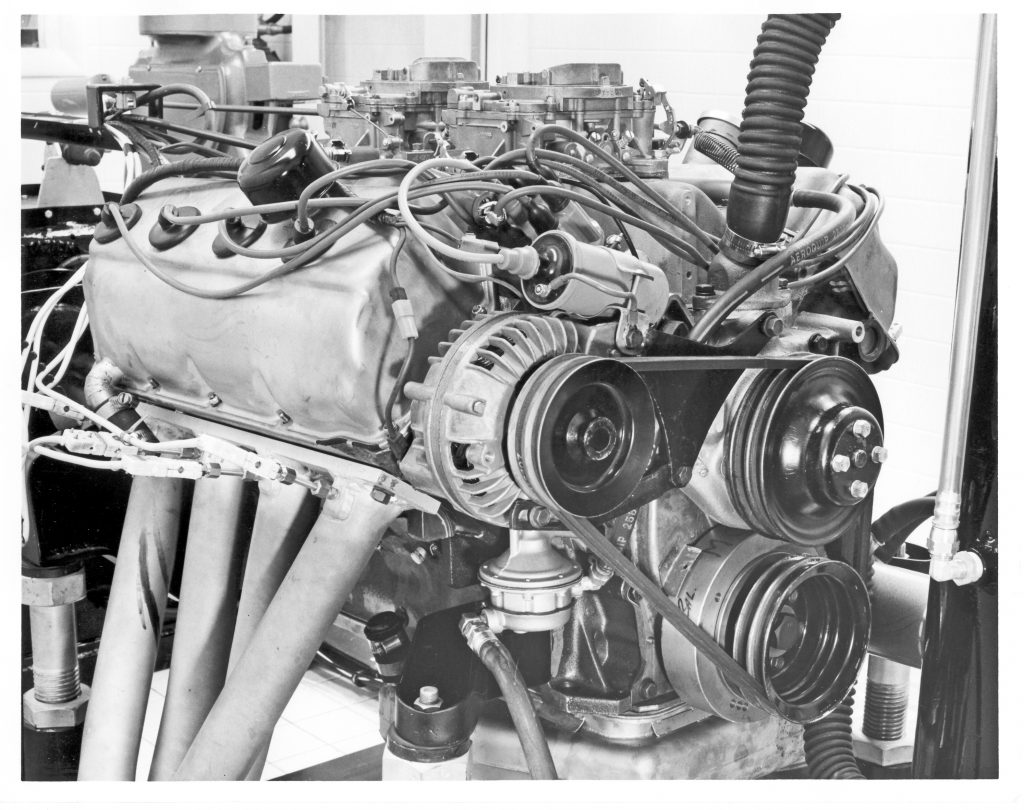

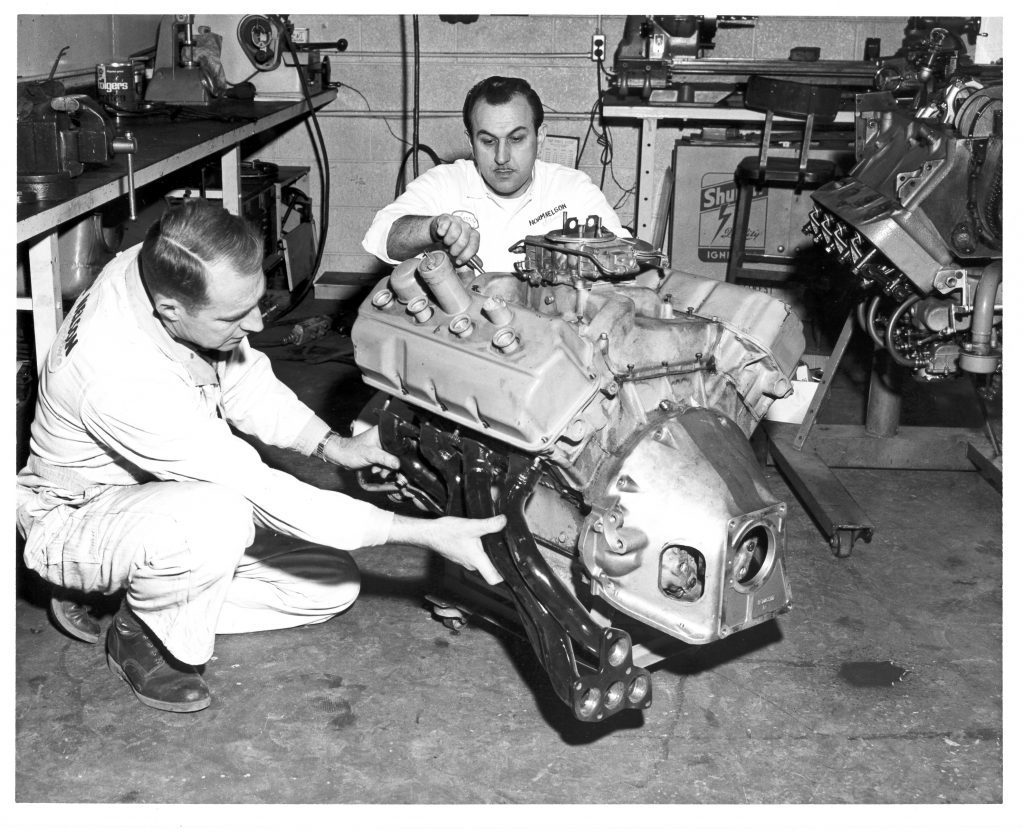

A Nichels Engineering 426 Hemi running with twin 4-bbl carburetors in the dyno room at the Griffith shop in 1965.

This issue became further complicated when on June 22, 1964, in an act of retribution, ACCUS (Automobile Competition Committee – United States), the U. S. representative of the Federation internationale de I’ Automobile, the world governing body of auto racing, stripped the United States Auto Club of all but one international race in its 1965 schedule–the Indianapolis 500. Principally affected by the move was the scheduled October, 1965 United States Grand Prix which had been awarded to Indianapolis Raceway Park under a USAC sanction. Thomas Binford, the President of USAC also happened to be the President of IRP. George Rand, secretary of the ACCUS committee said a majority of the nine member board agreed on penalizing USAC after “a thorough review” of a violation (by USAC) of the principles of the International Sporting Code. This announcement virtually ended a seven month controversy over the “suspended” status of USAC driver Paul Goldsmith. There was still on ongoing debate about ACCUS having “the authority” to rescind the earlier awarding of a race at IRP, but it came to naught, and the US Grand Prix remained at Watkins Glen, New York.

In the case of Goldsmith the point was moot in that he was contracted by Nichels Engineering and Chrysler to race in NASCAR for 1964. Now with Chrysler boycotting NASCAR in 1965, there would have to be a determination on Paul’s driving status. In a matter of no time, right after the first of the year, Henry Banks, the Director of Competition for USAC, hand delivered Paul Goldsmith his USAC competition license for 1965.

For the 1965 USAC stock car season Ray committed to running two cars; using Paul Goldsmith and Bobby Isaac as drivers. A.J. Foyt, who wanted to run at Daytona again, took a ride with Holman-Moody driving a Ford and no one could blame him. It was clear that Joe Leonard wanted to move into Indy cars. He had run five Indy car races in 1964, in addition to driving stock cars for Nichels, but it was obvious Joe wanted to run open wheel full time. Even though Leonard was the USAC Stock Car Rookie-of-the-Year, he would spend his time pursuing a ride in the upcoming Indianapolis 500. It was the same with Len Sutton who wanted to concentrate on returning for his seventh Indy 500. Speaking of Indianapolis, with Goldsmith approved to drive in USAC sanctioned races again, it meant Paul and Ray would be headed back to race in the Indy 500 in May.

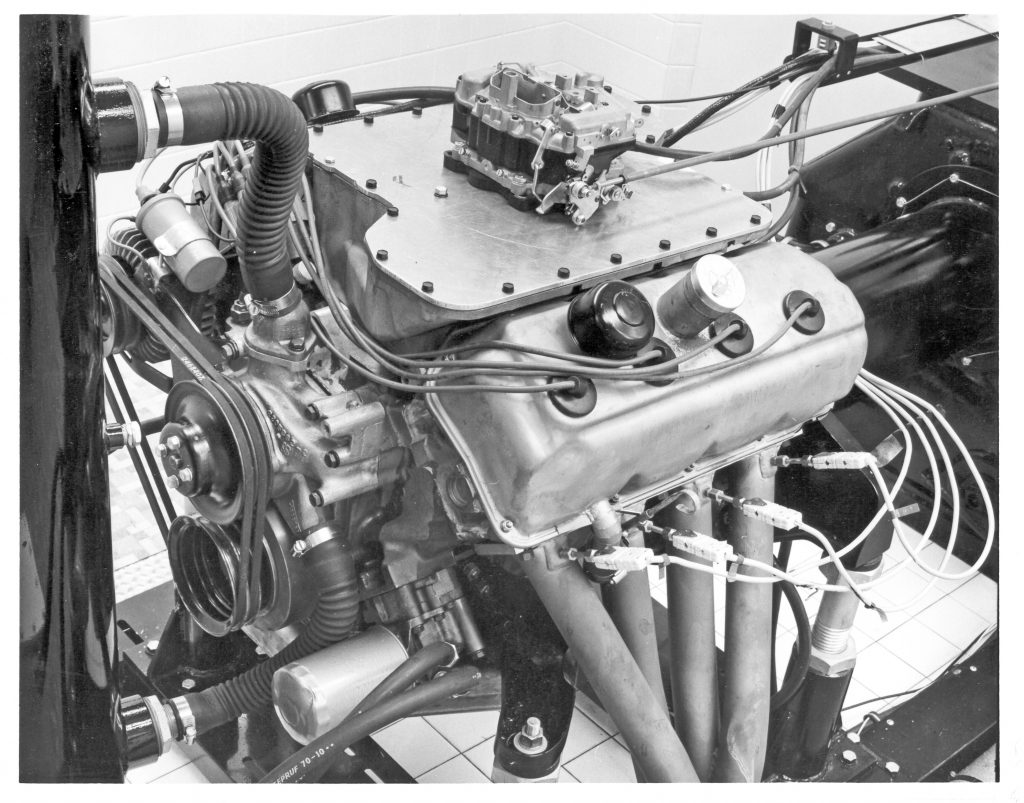

A single-carb Nichels Engineering 426 Hemi in the Nichels Engineering dyno room at the Griffith shop in 1965.

As the NASCAR season began, the Ford dominance started right away at the January 17th race at Riverside. Without Chrysler to compete, Ford and Mercury took nine out of the top-ten spots, with Dan Gurney once again showing his road-racing skills, winning his third straight Riverside race in a Wood Brothers Ford. It was clear the competition missed defending NASCAR Champion Richard Petty. Also being missed was David Pearson who had won more pole positions (11) than any other driver during the 1964 NASCAR season.

As Daytona Speedweeks began there was a buzz around the track that several Chrysler drivers were at the superspeedway and some sort of arrangement possibly might be reached. The presence of Goldsmith, Pearson, Isaac and Petty was reported in the racing trade papers, but these drivers were no where near getting into any cars. The fans clearly became unhappy. In a pre-emptive move on February 12th Bill France announced the updated rules for the 1966 NASCAR racing season. Although the 1966 rules offered some flexibility in wheelbase and engine specifications, it was taken with a grain of salt by the Chrysler contingent, because it didn’t address the current problem of Chrysler not racing in 1965.

The 1965 Daytona 500 came and went with Fred Lorenzen winning a rain shortened race. The first 13 places went to either a Ford or Mercury. Attrition was another problem with 14 cars going out of the race in the first six laps.

The high point for Chrysler in February was Lee Roy Yarbrough’s new track record run with a specially designed 1965 Dodge Coronet put together by Ray Fox. With a blown, fuel injected 426 Hemi nestled under the large bubbled hood, Yarbrough and Fox ran faster than anyone had ever run at Daytona, 181.818 miles per hour. Running at the track by themselves, for the sole purpose of the setting the new record, they still captured the attention of the racing public.

The low point for Chrysler in February was the news that on February 28th, the Petty race team decided to try their hand at drag racing at the Southeastern Dragway in Dallas, Georgia. During a match race with Arnie “The Farmer” Beswick, Richard Petty, driving a Barracuda dubbed 43 Junior, experienced mechanical problems coming off the line, broke loose and ended up heading into the spectator area. There were several spectators injured and one fatality as race track safety in those days was a bit lax. Both Petty Enterprises and Chrysler Corporation ended up being sued because of the incident.

Meanwhile back in Highland, Nichels Engineering was hard at work. One move by Ray Nichels that had gone unnoticed for several months was the hiring of Jim Delaney. The New Jersey native had been a well respected race car driver primarily in stock cars and modifieds. After a stellar driving career Delaney went to work for Bud Moore, while Moore’s cars were winning NASCAR championships. Nichels knew he could never replace Tiny Worley, but the hiring of Delaney turned out to be a Godsend when it came to picking up the pieces and getting back to racing. With his car building operation now expanding, Nichels started running weekly advertisements in the National Speed Sport News to let the racing community know he had open capacity for car and engine building. He had his group prepare the 1965 entries, the No. 36 Plymouth Hemi Belvedere for Paul Goldsmith and the No. 35 Dodge Hemi Coronet for Bobby Isaac. Nichels also made the decision to keep Joe Leonard’s 1964 No. 20 Dodge Hemi-Polara prepared to run in case a third car was needed.

Norm Nelson and Gerry Kulwicki (Alan Kulwicki’s father) set up a 426 Hemi that had just been shipped in from Nichels Engineering in Griffith, Indiana. Nelson’s racing operation was one of the best in the country during the 1960s and early 1970s

The first USAC race at Ascot Park in Gardena, California had finished a few months prior with Parnelli Jones the victor. That put the defending USAC stock car champion in a solid position as racing started up again in May. Clermont, Indiana, the home of Indianapolis Raceway Park was the first stop in 1965 for USAC. The “Yankee 300” was run on May 2nd, and the 300 miler was a wake-up call for those doubting the preparation of the Chrysler teams. Goldsmith took the pole with Norm Nelson taking the victory. Next they traveled north to Illiana Motor Speedway in Schererville, for a 50 lapper on May 23rd. Nelson got off to a great start capturing the pole, but it was Bobby Isaac who got his very first USAC stock car victory that day.

During their back and forth trips across Indiana, Ray Nichels and Paul Goldsmith spent as much time as possible at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway as Goldsmith was officially entered in the 49th running of the Indianapolis 500. Nichels and Goldsmith then forged a partnership with a primary sponsor, Jack Adams Aircraft of Memphis, Tennessee. Nichels also enlisted additional support from Goodyear Tire and Rubber and Champion Spark Plug. Ray then finally brokered a deal to obtain a newly constructed rear engine car from long-time friend Ted Halibrand.

The car was a Halibrand Shrike. It was one of seven Shrikes manufactured in less than three months (mid-January to mid-April) that were delivered to the Indianapolis Motor Speedway for various race teams. Goldsmith, Lloyd Ruby, Jim Hurtubise, Johnny Rutherford, Roger McCluskey, Joe Leonard and Chuck Rodee were all given opportunities in the newly manufactured Halibrand cars. The design was quite unique, using magnesium bulkheads with stressed aluminum skins. There was a grand total of 68 metal castings used in the car’s construction, probably the most ever in a race car of this type. The Shrike was likely one of the lightest to ever turn a wheel at IMS at just under 1200 pounds, dry.

Halibrand also built superb two-speed transaxles for these cars with a quick change differential. With the introduction of the Cooper Climax in 1961, rear engine cars were making a larger presence at Indy every succeeding year. Halibrand recognizing the evolution of Indy style race cars became a chassis constructor in addition to the myriad of other products he was supplying to the racing community. His cars were built utilizing modern aircraft techniques. One of the keys to the Shrike was its cast form frame construction that allowed quick modifications to accept any type of engine. Most of his customers for this Indy 500 were using Ford’s double overhead cam engine. The use of the Ford engine at Indy had also been quite an evolution. In 1963, only two Ford engines were entered in the Indy 500 to complete against the legendary Offy. In 1965, 25 were now predicted to make the starting grid using every bit of the 490 horsepower that the eight-cylinder engines were designed to deliver.

Bobby Isaac in his Nichels Engineering 1965 Plymouth Belvedere

In the case of Ray Nichels and Ted Halibrand, they tried a unique approach for their selection of the car’s source of power. The No. 35 Jack Adams Aircraft Special would utilize a substantially modified four-cylinder Offy powerplant. This engine had been produced using engineering support from Chrysler who had contributed computer information to help build it. Householder was once again trying to extend Chryslers racing presence at every opportunity. The new improved Offy delivered better than 500 horsepower, yet displaced only 240 cubic inches. The engine had the bore enlarged one sixteenth of an inch and the stroke shortened one-half inch. It turned a little more than 7,500 rpm to develop its power, with the idea being to get away from the terrific low-end torque and put the effort on the top end by turning it tight.

The engine was made of lightweight aluminum, tipping the scale at only about 300 pounds. Going to the 240 cubic inch Offy was an effort to permit the driver to get back on the throttle sooner in the turns. This was something that had to be handled with care with the larger 255 cubic inch Offy, for too much throttle too soon and the car would break loose. The torque on the 240 cubic inch Offy was down, but the horsepower was up, the same concept employed by Ford. The dyno work was done by Dick Jones, the manager of Champion Spark Plug’s racing division based in Long Beach, California.

With Tiny Worley gone, this particular project fell into the capable hands of Ernie Dascenzo to get the car ready for Indy. But practice laps did not go well. It became clear to many on the Nichels team that not enough time had been spent understanding the conversion to a rear engine car. Goldsmith was very uncomfortable driving the car and no matter what chassis adjustments were made, the car just didn’t appear to be stable at the higher speeds being seen at the speedway. To further magnify the problem, some Chrysler engineers got involved at one point late in the practice schedule, modifying the front suspension system, upsetting the geometry while trying to relocate the roll center. In the end the No. 36 Jack Adams Aircraft Special car just wasn’t stable enough for what was about to be the fastest field ever at Indy. The problems couldn’t be exclusively blamed on the car either, because six of the Halibrand Shrikes made the starting 33 for race day. On the last day of qualifying, the Nichels Engineering team pulled their entry, and with it the last opportunity that Paul Goldsmith would ever have to race in the Indianapolis 500.