Driving Lessons

OK, most of our readers have learned to take our tech editors word as gospel when it comes to tech. Sure, some readers have taken him to task for his political views (somewhere out in right field about a country mile past Rush Limbaugh), now E-boogers gonna break new ground by teaching you how to drive!

– C.GDriving Lessons from Ehrenberg

Are You Ready?click to enlarge

Stupid driving mistakes can ruin your day, and your

classic Mopar. They can also make your face red!

Drive it like you stole it dept. Keeping that virgin Mopar in…virgin

DRIVE TIME

A lot of us have gotten a bit complacent on the road. Todays computer-controlled ABS, stability and traction control, and FWD or AWD systems have relegated typical daily driving to something of a point n shoot activity. But what happens when you take that classic Hemi Super Bee, 440 Dart, or DeSoto Adventurer out for a spin and decide to drive it like it was built to be driven? Usually, given light traffic and good weather, nothing (except a broad grin). And some of us are brave (or stubborn) enough to actually drive 60s Mopars every day. Some of us even hammer them, Im happy to report. But emergencies do occur, and they wont take a holiday just because youre wrapped in 4,000 pounds of 60’s Mopar iron. For these situations, you probably need at least a refresher course, since there are several eventualities for which you are likely ill prepared. Theres also some underground gotta-know tricks they didn’t teach you in school. With our Beepers recent brake upgrade fresh in our minds, lets begin with stopping.

Major-league multi-car pileups seem to happen on the I-5 corridor (U.S. west coast) with alarming regularity. But they can happen anywhere – this one was in Sydney, Australia. Ehrenbergs tips can help make you a spectator instead of a victim, and keep your Mopar unscathed for future generations.

MBS

Not ABS. MBS. That what we have. Manual brake systems. OK, some of us have mushy vacuum power assist, but, unless youve been on a resto mission from hell – getting that 1971-73 Sure-Brake system dialed in, most of us find it all too easy to lock the wheels. While proper proportioning can make that harder to do, its still far from impossible. Especially on road surfaces that are less than ideal, or in inclement weather.

In the high school drivers ed of yore (remember that? When you looked at the chestwork on Suzie sitting next to you, instead of the road…) they taught you to pump the pedal in low-traction situations. Ehrenberg says: thats BS, pure and simple. No matter how fast you pump, youll be off the pedal for at least 40-50% of the time. And your stopping distances will be astronomical. Please if not for yourself and those around you, then for the sake of that valuable Mopar throw the notion of pumping out with those punctured Chevy rocker arms and snapped Pontiac iron con rods.

Now, locked wheels are, except in a few very specific cases well get to in a moment, bad news. Especially rear wheels the laws of physics dictate that a car with the rears locked solid must spin. This is not a good scene. So…

Heres the straight scoop: Threshold braking. Wazzat? Really, simple. Just apply as much pedal pressure as you figure youll need to stop in the allotted distance. If a wheel locks, just reduce the pedal pressure lighten up a skosh until you feel the wheel begin to rotate again. Then, immediately, get back into the brakes as hard as necessary. This works on most road surfaces, but heres a tip: If youre on gravel, or deep snow, then the car will actually stop quicker with all four locked. It will stop quicker than an ABS equipped car! This, of course, assumes that theres nothing nearby to hit. Which brings up steering….

STEER CLEAR

Say youre coming down a curvy, snow-covered mountain road. Theres a sharp left turn, and you, or course, turn the wheel. But its too much, and the car begins to skid off the road to the right. Remember the drivers ed instructors words now: Steer in the direction of the skid…. What the hell does that mean? Quick, which way to turn the wheel? Natural instinct would have you turn the wheel more to the left, away from whatever trees or boulders are off to the right. But instincts arent always right. The term skid is really just so much bull, anyway. Whats happening is theres an excessive slip angle between the tire and the road. Turning the wheel more just makes it worse. Heres the phrase that pays: open the wheel. What that basically means is to turn the steering wheel dead-ahead momentarily to let the tires regain their grip. Then turn in again. Repeat as necessary. This works. If you have trouble with this concept, a great trick is to apply a narrow strip of bright yellow electrical tape around the steering wheel rim at 12 Oclock. Leave it there permanently.

click to enlarge

Of course, another aspect of safe driving is avoiding those nasty green stamps. Is that a younger Ehrenberg receiving one? Well never tell!

Now, heres some food for thought: What happens on that snow-covered road at 30 MPH is exactly the same but at a lower speed as what happens when youre driving like Ehrenberg on a winding, dry road in the summer way too fast, in over your head. And the same bailout works.

click to enlarge

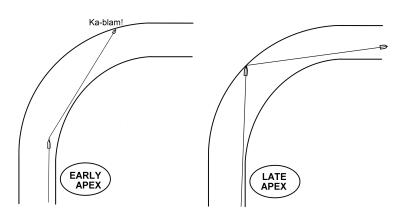

While theres no hard and fast rule, in the vast majority of highway situations, youre better off braking in a straight line and turning in late. The reasons are obvious when you grasp the concept, but sometimes seem counter-intuitive.

STEER LATE

Ok, its that summer afternoon we all live for, and youre hammering on some unfamiliar twisties. Oh, Jeez, this next curve is tighter and sooner than you expected. You hug the inside, to begin making the turn as soon as possible, assuming thatll give you more time and space.

Bad idea. Youve just done what race drivers call an early apex. As the drawing above shows, youve effectively sealed your own fate. Plus, youve given up valuable straight-line braking area, where you might be able to cut your speed some (before impact?) And this brings up another point: Unless youre really good, try to do all your braking in a straight line. Actually, our classic Mopars were decent at what the racers call trail braking, especially if you combine it with some left foot braking and a little throttle. But if youve never done this, a Long Island Expressway or Santa Monica Freeway exit ramp isnt the place to learn! A big pole-free parking lot, or, even better, open-track day at a local road course, are way better ideas.

OK, now, on to the killer.

ONE CAR IS ENOUGH

You see it in the local newspapers all the time: Joe Blow, 19, of Mud Flats, ran off the road today on the state highway outside of Smashburg, hit a tree, and was DOA. Subsequent testing found his 82 Camaro to be in good condition and police found no traces of alcohol or drugs in Joes blood. Fell asleep at the wheel the reporter (or fuzz) usually guesses. At two in the afternoon? Maybe, but heres the real cause in 90% of the cases:

Joe did nap sort of for a fraction of a second. Maybe putting a different Metallica cassette in the J.C. Whitney stereo. Maybe reaching for a fresh butt. Whatever. In being inattentive for those few hundred milliseconds, he put the two right wheels off onto the shoulder. The sound and feel of the gravel quickly snapped him back to attention. He cut the wheel hard left, transferring most of the cars weight onto the right side. But the right front wheel was now on a low-friction surface, and the car didnt respond much to Joes input. So he yanked more.

click to enlarge

Human error causes the vast majority of one-car crashes. In this famous scene at the 71 Indy 500, the Challenger pace car driver missed his braking point because someone removed his marker cone. This resulted in fatal spectator injuries. But, was it his fault?

Finally the car moved over the few feet back to the macadam. And, like a good drag racer, the tire hooked right up. But the wheels where now pointed way too far left. Result: loop city. Check the accident report: Betcha the tree that got whacked was on the left side of the road, and odds are that Joe hit it with the back or the side of his Chevy. A helluva last ride. Accident reports usually refer to this type of wreck as driver error overcorrected.

The cure for this, other then obviously being attentive 100% of the time, is really simple. Race drivers have a term for this, too: If you go off, stay off. In other words, if you drift off, even partially, onto the shoulder, lightly apply the brakes until youre down to something like 30 MPH or less. Then steer back on and crank up Buddy Holly on your Darts 8-track. And punch it.

HEADS UP

We all see those nasty 42-car chain reaction freeway crashes on TV. What idiots we think. Hey –70 MPH in a pea-soup fog? True enough.

But for every one of those, theres a thousand 3 or 4 car pileups that barely makes the news. In fact, Ive been in several. But Ive never even dinged a bumper. Huh?

Heres the way to make car crashes almost fun: Avoid them. The car ahead of you plows into the hapless overbraking slob in front of him. But, if youre on the ball, using the E-booger technique, you can duck left or right and simply drive around the carnage without even tapping the brakes. Then the turkey behind you can blast the guy that was in front of you. Ka-blam! Thats how its done, boys and girls.

All it takes is getting out of the habit at blindly staring, almost fixated, and the guy in front of you. You should be looking a few cars in front of him. If youre a serious speeder, like me, you should be looking a good 600 – 800 feet ahead, minimum. One overreacting dimwit can start a chain reaction in an eyeblink. Now, Id like to tell you to simply not tailgate. But, as any driver suburban interstate will tell you, unless you want to go 30 MPH less than the traffic flow, and hear more screamed curse words than at a Lenny Bruce show, thats simply not possible. So simply keep you left foot poised over the brake pedal (to cut reaction time), and remember this sections heading.

If a truck or SUV in front is blocking your big-picture view, do something about it. Or back it down.

click to enlarge

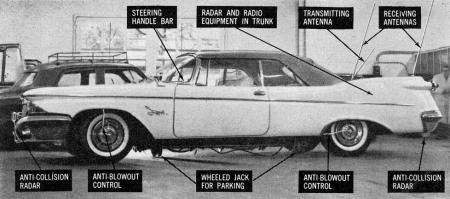

Safety cars are nothing new. In the early 60’s, a Belgian mechanic showed this 1960 Imperial with crash-avoidance radar, tire-pressure monitoring, among other goodies. It ever featured remote-start, a now-common convenience feature.

HAMMER AND LIVE

There are several parts of the world, mostly in South America and a few places in western Europe, where the highways handle, with relative safety, quite a few more vehicles per hour than our roads do. A recent study (in Bogota, Columbia) unearthed the reason: (Surprise, surprise) Aggressive driving. Hey, if youre on a multi-lane interstate, and some slob is doing 10 under in the left lane, and theres 200 feet open in front of him, I dont know about you, but that space is mine. And so is the next gap. And so on. Its pretty easy to average 10 to 20 MPH more than traffic flow if youre good, and, with so many vehicles protecting you from those nasty radar beams, this is pretty safe, at least from a keep-your-license point of view. While some people call this weaving, I call it a fun way to save time and stay awake. However, if you do this without honing a few skills, you will, its true, probably increase your chances of being involved in a fender-bender.

Skill number one is a variation of Heads Up. Its simply the requirement that you be constantly be aware of exactly whos around you and what they are doing. If you are in the center lane, you need to be able to recite, to yourself, at any given instant, what all the cars in your general vicinity — in all lanes — are doing, and are likely to do. Weve all seen a drivers head twitch or twist a second or so before his turn signal comes on. Weve also all seen the schmucks yakking on a cell phone, lighting a cigarette, balancing a coffee and sandwich, futzing with the kids, etc. You know these turkeys cant be prepared for Jack, so you have to be.

Generally this involves always knowing, before it happens, what youll do if that SUV doesnt see you sneaking up on his right and cuts you off. You have to have a ready backup plan, updated continuously: Whether its knowing that theres room on the shoulder, hard braking, whatever.

Interestingly, over the course of two million miles (give or take) of aggressive driving, Ive learned that the standard drivers ed teaching of signal your intentions, be visible – make sure the other guy sees you, etc., is, many times, the exact opposite of what you really need to do if you wanna get to work on time. Usually, youre better off sneaking by quickly before they even notice you like a shark on asphalt. If they dont see you, they cant do something stupid by way of a reaction. But youve gotta get by em fast – before they blink! (Of course, on a road with at-grade intersections, youve gotta be seen. A quick headlight flash at that guy stopped at the crossroad can save your butt.)

AND BEYOND…

Sure, theres lots of other tricks in this old dogs playbook. (Thats how I got to be an old dog. Remember the Harley riders credo: There are old bikers. There are bold bikers. But there are no old, bold bikers). Some are right off the road course, but some are in agreement with modern drivers ed. Take a high-speed drivers ed course, offered at most road courses regularly, if you want your eyes opened and pulse quickened.

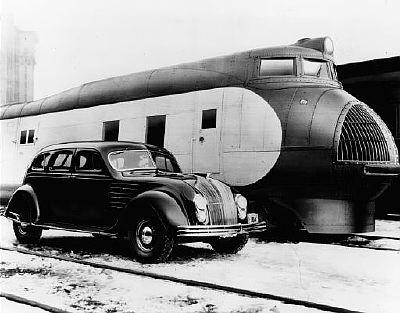

It can be argued that Chrysler was the real innovator in safety cars, with the 30’s Airflow cars setting new standards by having a welded-steel passenger safety cage, a feature that would become standard in almost all Mopars by 1960.

Always know the limits of your Mopar and the road conditions and design. On a race track, you can hammer into a curve blindly without knowing whats around it there are corner workers who will wave the yellow (or red) flag well in advance if somethings amiss. And, on the track, most corners usually have either plenty of runoff room, a gravel trap, or, at least, a tire wall to reduce the pain of impact. On public highways, these features are seldom found.

Thats about all we have time for. Well leave you with a final thought provoker: When is a green light not what it seems? Easy. When you didnt see it turn green. Thats called a stale green light. It could turn red at any time. And the amber might be much shorter than you expect.

Drive fast. But drive carefully. These dont have to be mutually exclusive! MoPar to ya.

Comments are closed.