Chrysler’s Stock Car Connection — Part 14

HOW SWEET IT IS: Chrysler clinches its third National Stock Car Championship.

By Wm. R. LaDow Photos from “Conversations with a Winner—The Ray Nichels Story.”

When we last left off, Chrysler was heading into the 1967 Firecracker 400 at Daytona.

The July 4th race at Daytona served as the approximate mid-point for the NASCAR season. By the time the crews reached the stock car racing Mecca opened by Bill France in 1959, there had already been 27 races run in the 1967 schedule, with still plenty of racing to do. For Paul Goldsmith, the Firecracker 400 represented his 12th race entered. Goldy had run hard and fast and every lap of every race represented an opportunity for Nichels Engineering to gather more data and share more insight with the other Chrysler teams. The stoic Goldsmith, proved to be an engineer’s dream when it came to sharing information about what he was experiencing on the race track. His unique perspective made every team better thanks to those who properly utilized the data documented by both Nichels Engineering and the Chrysler engineers. This race would be no different.

There was something uniquely interesting about this visit to Daytona though. After both Ford and Chrysler had made public statements about the interpretation of NASCAR’S inspection rules and regulations during the course of the season, it got downright ugly during inspection at the “Big D.” NASCAR inspectors showed up on opening day with new and more demanding body templates. When inspection process began, only one car of the first 50 checked, Bud Moore’s Mercury being driven by LeeRoy Yarbrough, passed inspection. Bill France explained to anyone who would listen that it was time to insure that the cars being raced were the same as available to the public in the auto showrooms across America. That meant the cars had to fit the body templates without exception. France additionally reminded the racers that his people had been warning the various race teams and car manufacturers that by the time the Firecracker 400 was run in July, NASCAR would be tightening up inspection. He was true to his word. Probably the most accurate statement regarding the NASCAR inspection process was voiced by Jon Thorne’s crew chief, Mario Rossi, when he said “We were about an eighth of an inch off and we had to go take a hammer and beat on a $20,000 race car.” When the inspection proceedings were completed there were still a few raised eyebrows when looking at the what could only be described as “a metalworker’s piece of art” in what would later become the race pole sitter (at a speed of 179.802 mph) the No. 26 Junior Johnson Ford driven by Darel Dieringer.

For Nichels Engineering and Chrysler Corporation, July 4th started out as just another day at the office. But rain became a problem from the day’s onset and everyone recognized it was going to be a long, long race. The 10 AM starting time got delayed after rain pushed through the Daytona Beach area. Then while getting the track dry, a faulty sweeper deposited a bunch of metal needles that had to be painstakingly collected, for fear of tires being punctured during the race. The track was finally cleared for racing with the green flag flying at 10:30 AM.

Buddy Baker immediately pushed his No. 3 Ray Fox Dodge Charger to the front and registered the fastest race lap ever recorded at Daytona at 180.772 mph on his third pass by the scoring stand. The hammer was down, and the entire field was on the move, save one. Richard Petty wasn’t able to get his Plymouth started for the parade lap, flooding the engine and fouling some spark plugs. By the time Richard took off after the field, it was clear he had troubles. He returned eight laps later for a complete carburetor replacement, effectively eliminating him from being competitive for the rest of the day.

Baker led the charge as he was being chased by Bobby Isaac in the No. 71 K&K Insurance Dodge Charger and David Pearson in his No. 17 Holman-Moody Ford. Defending Daytona 500 winner, Mario Andretti, again driving a Ford for Holman-Moody, got an unscheduled ride into the track wall on lap 20. While running down the front stretch battling for position with Paul Goldsmith, their cars got together resulting in Andretti ending up in a long slide, hitting the wall, cutting a tire and finally stopping in the grassy area between the track and pit road. An angry Andretti complained to race officials that Goldsmith first squeezed him (they were both pursuing Cale Yarborough) and then turned into Mario, wrecking him. Goldsmith continued on without incident. Following the yellow, the pace picked back up with the lead changing 25 times over the next 80 laps. Even Sam McQuagg took the lead briefly in a two-year old K&K Insurance Dodge. Rain again stopped the race at the 105 lap mark and it didn’t start again until four and a half hours later. By the time the Firecracker restarted it had become a race of Ford products. Cale Yarborough, Dick Hutcherson, Darel Dieringer and David Pearson challenged each other until a last lap pass by Yarborough pulled him in front of Hutcherson for the victory, over seven hours after the race had begun.

Unbelievable You Say … Well, Believe It !!!

What came after the Firecracker 400 are what storybooks are made of.

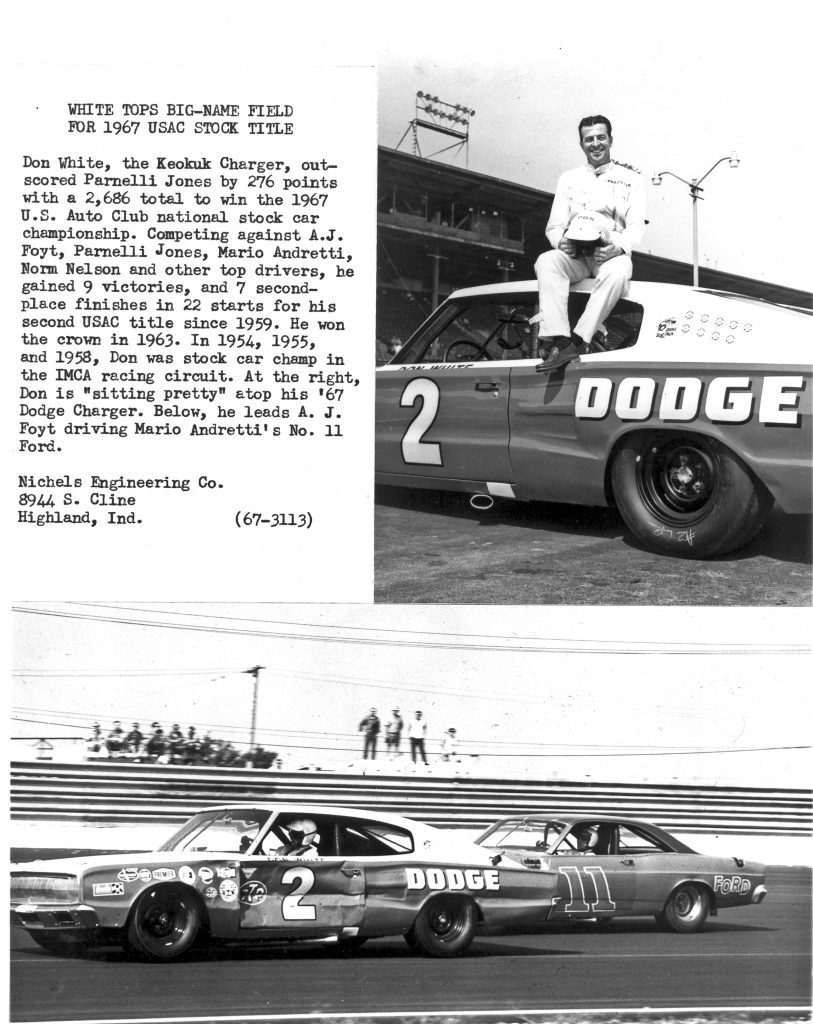

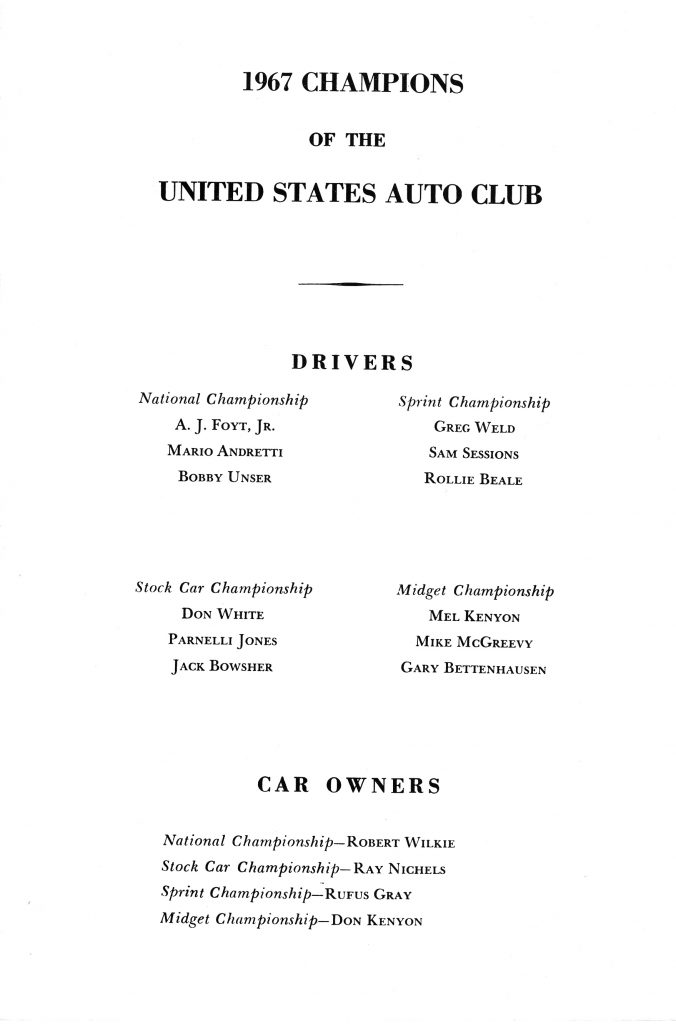

USAC was continuing to run a series of races in and around Chicago’s Soldier Field, while NASCAR had started their northern tour. The following week found NASCAR at the one-mile paved oval in Trenton, New Jersey and USAC again at the Soldier Field short track. The results were identical, Plymouths won. The victors were Richard Petty in Trenton (Goldsmith finished fourth) and defending USAC Champion Norm Nelson in Chicago. Don White was the pole sitter for that race and finished second behind Nelson.

On the day after Norm Nelson’s victory at Soldier Field, Ray Nichels sensed something very special was happening. He had watched Don White for over a year now, working on the cars side-by-side with Nichels mechanics and Chrysler engineers. Ray had witnessed Don win eight races in the 1966 season, as White was getting accustomed to the Nichels cars and the way Nichels employees worked as a team. Don had done everything Ray had asked of him, and much, much more. Ray knew it was now his job to insure that Don had everything he needed to win his second championship.

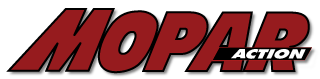

On Sunday, July 9th, Ray felt it all come together. Don White went out on the Milwaukee Mile and, along with Jack Bowsher, conducted what many believed was Milwaukee’s most thrilling 200 mile race in the 19 year history of the event. In front of 27,000 rabid race fans, A.J. Foyt, Parnelli Jones, Mario Andretti, Bowsher and White battled fender to fender on the paved oval. Bowsher, new in USAC and the race pole sitter, had no problem putting both Andretti and Jones into the fence when confronted by them one-on-one. Foyt battled long enough to drop out after his Ford overheated. That left Bowsher and White to battle it out. Bowsher tried to outrun Don’s Charger, gaining a substantial lead that evaporated when Jack realized he had run himself low on fuel. With 16 laps to go it became a see-saw battle between the two. With a mile and a half to go, White went for the pass and made his Nichels Dodge Charger stick. In capturing the victory, Don set an all-time Milwaukee 200 mile stock car record of two hours and 17 minutes, for an average speed of 94.266 mph. White’s fourth win of the season catapulted him to the top of the USAC season points standings.

On July 13th, USAC returned to Soldier Field and Don White took the pole and added more championship points by finishing second in the feature. Two days later on the 15th of July, White finished first in qualifying and finished first in the race. Nichels thought to himself … “Don’s on his way !!!”

Meanwhile in NASCAR, after the Trenton race, there was a 100 mile event at the one-third mile Oxford Plains Speedway in Oxford, Maine. Because Cotton Owens had chosen to skip the northern region races for cost purposes, he gave Bobby Allison the freedom to get another ride for the tour. Allison promptly won the July 11th race at Oxford in a 1965 Chevy sponsored by J. D. Bracken and a few days later became a victim of Chrysler’s corporate politics, losing his Chrysler ride with Owens. It was a blunder by Chrysler corporate brass and something that Owens felt terribly about. But that didn’t stop the racing from continuing. Two days later, on July 13th, Plymouth once again was in the NASCAR winner’s circle with Richard Petty winning on the half-mile dirt at Fonda, New York. On July 15th, Petty won again at Islip, New York and on the 23rd, Richard got back to business on the tracks down south by winning the Volunteer 500 at Bristol. It was Petty’s 16th victory in 33 races. Chrysler was now clearly dominating American stock car racing.

On July 29th, Petty won the 200 miler in Nashville, staged at the historic fairgrounds half-mile paved oval. Up north, Don White finished third overall, with fourth place and second place finishes in the two heat races making up the Kawartha 250 held at Mosport International Raceway in Bowmanville, Ontario, Canada.

By early August it became clear to everyone close to auto racing, that Chrysler was on the march. On August 5th, Don White pushed his flaming red and white Nichels Engineering Dodge Charger to take both the pole and feature race victory at Soldier Field. Of the eight races contested during the 1967 season in one of Chicago’s legendary landmarks, White and Nichels Engineering had captured five pole positions and entered the winner’s circle four times. After the USAC schedule ended its 1967 season commitment to race organizer Perry Luster, they headed back to the Milwaukee Mile. In the 150 mile race on August 13th, White copped a solid second place finish after being forced to pit on one more occasion than the race winner Jack Bowsher. White’s car experienced what appeared to be an A-Frame failure, causing Don terrible handling problems. Nonetheless, his second place finish kept him in the hunt for his second and Nichels’ Engineering third national stock car championship in USAC. The next race at Milwaukee was run four days later on August 17th. The 200 miler proved to be a long and unprofitable day for White and Nichels Engineering. Don still finished the day atop the USAC season points standings, but for this race he came in at 27th place, far out of the money.

Following White’s tough luck in Milwaukee, he and Ray Nichels regrouped back at the “Go-Fast Factory.” With Don working with Jim Delaney, Jerry Govert and Minnie Joyce, the Nichels Engineering team readied themselves for their next five USAC races. Don wasn’t scheduled to return to NASCAR country until the National 500 at Charlotte in mid-October. This gave him and Ray time to chart their course to a national championship.

Their quest started in Springfield, Illinois on August 20th. Ray had always loved racing at Springfield and this day it was no different. The race day started out as a challenge after an all-night rain had left the one-mile dirt oval a quagmire. The No. 2 Nichels Engineering Dodge in the superbly talented hands of Don White started out by setting an all-time track qualifying record. White manhandled his mount around the Illinois State Fairgrounds track in 37.21 seconds to post a record-breaking speed of 96.748 miles per hour. For good measure Don went out and took the victory too. Five days later, Don and Ray were in Indianapolis for the Indiana State Fair Century 100 and they came loaded for bear.

White again started his race day by taking the pole position for the 100 lap, 100 mile race, setting a new track qualifying record of 91.394 mph. The start of the race was delayed for 45 minutes as track workers repaired 50 feet of guard rail that A. J. Foyt had torn loose during qualifying, but the delay didn’t hamper the Nichels team in any way. In front of an Indiana State Fair crowd of almost 18,000 (a record), Don started the race strong and finished it the same way. White surrendered the race lead only twice, both times while trapped in the pits, behind A.J. Foyt and Parnelli Jones. Don took the lead back for the final time on lap 71 by passing Jones on the outside. When White took the checkered flag for his third straight Indiana State Fairgrounds victory, he had also established a new track race record. It was a solid day for the Mopars, with Al Unser coming in third, and Paul Goldsmith finishing fourth with only seven and a half seconds separating the first four finishers.

Two days later the Nichels race team showed up in Wentzville, Missouri at Mid America Raceways in an effort to keep Don’s two race win streak alive. The paved road course was less than 150 miles from White’s hometown of Keokuk, Iowa and it gave many of his fans the chance to see the “Keokuk Komet” up close. Don and his Nichels Engineering team didn’t disappoint. The meticulous preparation by Ray Nichels’ race team was apparent to the 20,000 fans ready to witness the Missouri 200. Parnelli Jones started the day strong by taking the pole position, but his good fortune wouldn’t last. At the green flag, Jones lit out with Mario Andretti, A.J. Foyt, Norm Nelson and White (in the order of their qualifying times) in pursuit. It didn’t take Don long to work his way up to second place and on the 10th lap, he took the lead as Jones pitted with mechanical troubles (later being revealed as a burned valve.) Another sign that this was to be Don’s day, was not only was he driving flawlessly, but his Nichels crew registered the quickest pit stop of the day of any competitor, with a 20 second stop for two left side tires and fuel. By the 36th lap (of the 71 run,) Don had lapped the field. White showed ‘em all in the “Show Me State” by taking the checkered flag, a full lap ahead of the second place finisher, Norm Nelson. Third place went to Bay Darnell, in another Nichels-built Mopar for a one, two, three sweep for the Pentastar brand. Wentzville was Don White’s ninth victory (and third in a row) of the 1967 USAC season.

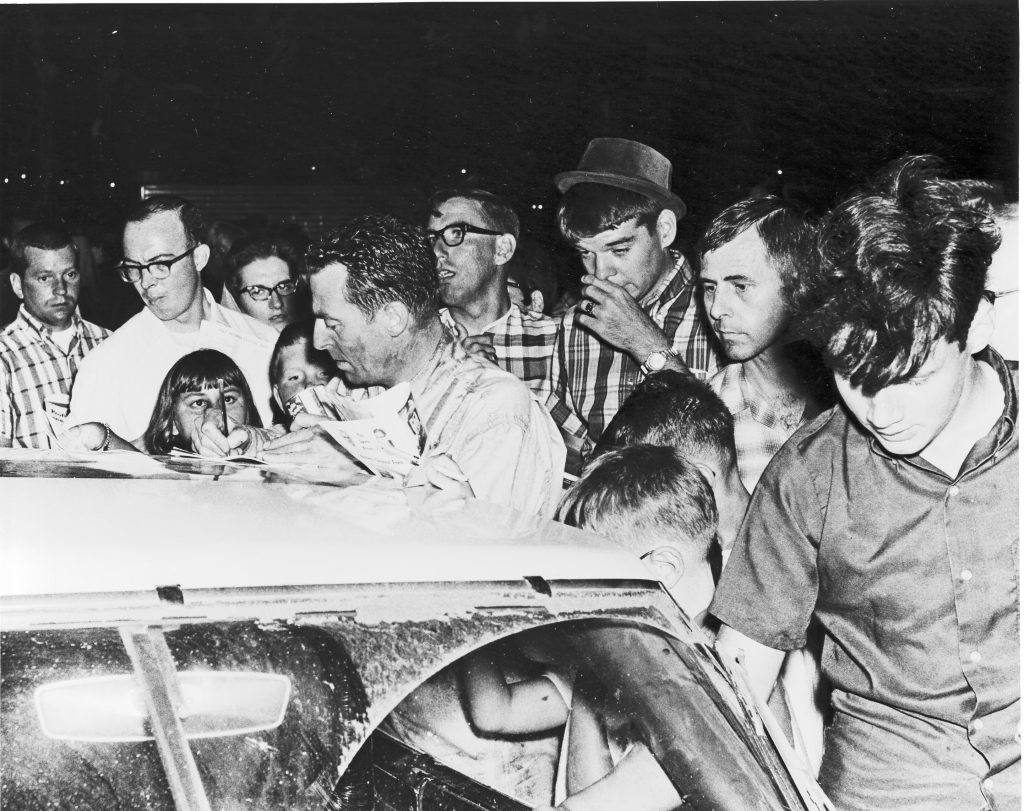

The final USAC race of the year was in Milwaukee, a 250 miler, the longest of the season at “The Mile.” The Nichels team knew they bordered on a third national stock car championship. Don White qualified with a time of 35.569 seconds around the legendary oval, though fast, was not fast enough to displace Jack Bowsher who came in at 34.896. White started on the inside of the third row and knew all he had to do was drive “his” race. He was a man on a mission. He stayed with the leaders early and the race turned into a see-saw battle that kept the 22,000 plus fans on the edge of their seats. During the course of the contest the lead changed hands 10 times. White stalked the leaders, A.J. Foyt, Jack Bowsher and Parnelli Jones who were all piloting Fords. Four different accidents and 28 laps of yellow flags keep everyone focused on the action. White, pushing hard as always, had the Hemi in his Charger expire on lap 147, but it no longer mattered. The math had already been worked out. Don White was now the 1967 USAC National Stock Car Champion.

In the meantime, while Don White had earned his second USAC stock car championship for Nichels and Chrysler, a phenomenon was occurring in NASCAR. At the heart of the this phenomenon, was Richard Petty, his brother Maurice and their cousin and Petty Enterprises crew chief, Dale Inman. Taking part and parcel from Nichels Engineering, the Petty team, refitted one of their 1966 Plymouth Belvederes, nicknamed “Old Blue” and with the magic only they could weave, set all of stock car racing on its collective ear.

They won. Then they won again. Then they won again. If fact for almost two months of the NASCAR schedule, they didn’t stop winning. Richard Petty was crowned “King Richard” and for good reason. NASCAR’s most personable and by now their all-time winningest driver, did something no one had ever done before (or since). He and his Petty team won 10 NASCAR races in a row.

It didn’t matter where they raced, dirt track or paved, short track or speedway, they were unbeatable.

Richard admitted later that his Plymouth was running so strong, there were times he sandbagged, because of his fear that NASCAR would start legislating again him and his team’s equipment, much the way NASCAR outlawed the Hemi in 1965. After Richard’s victory at North Wilkesboro, the NASCAR season finished with three more races, with Buddy Baker getting his first Grand National victory on the high banks of Charlotte. Meanwhile, Don White ran both Charlotte and Rockingham to bring his NASCAR season to a close.

In 1967, Don White ran 22 races in USAC, earning nine victories, nine poles, 18 top fives and $29,515 in purse money. He raced in NASCAR six times, earning one top five and three top tens, taking home another $8,400 in winnings. His teammate, Paul Goldsmith, competed in 21 NASCAR races finishing in the top five seven times (33.3% of races run), collecting purses of $35,360 and placing him in 11th place in the NASCAR season standings. Paul also fared well in his handful of USAC appearances, running with the leaders without exception. Goldsmith’s 13 DNF’s in NASCAR in no way reflected how important his contributions were to Nichels Engineering and the engineering staff of Chrysler Corporation.

For affirmation of Goldsmith’s and White’s contributions to Nichels Engineering and Chrysler corporate, there was a simple equation. In 1967, Chrysler Corporation and Nichels Engineering participated in four stock car racing sanctioning bodies, NASCAR, USAC, ARCA and IMCA. They won national stock car championships in each one. Whether it was Richard Petty in NASCAR, Don White in USAC, Ernie Derr in IMCA or Ignatius “Iggy” Katona in ARCA, the math was simple. Four race teams running Chryslers, four championships. This was the second time that Nichels Engineering had been an integral part of such as feat. The first time was in the early 1960s, when Ray Nichels managed the GM-Pontiac stock car racing program.

When Ray Nichels surveyed the racing landscape at the end of 1967, he realized he had witnessed a tremendous amount of growth in Chrysler’s stock car racing program. It was Chrysler corporate engineering with George Wallace, John Pointer and Larry Rathgeb, whose scientific approach coupled with hands-on engineering, was clearly making breakthroughs in the design of faster and safer race cars. It was also the growth of his own Nichels Engineering staff, who were now investing a minimum of 1,000 man hours in each race car they built and never failing Ray when the chips were down. The “Go-Fast Factory” now just three years old, had become the masterpiece of the racing engineering that Ray had hoped. Ray had also seen the Friedkin team win four races, Jon Thorne’s team win a race, and Ray Fox’s team with a race. He saw another Mopar driver and car owner, independent James Hylton, defy all odds and gain 26 top fives and 39 top tens (out of 46 starts) to end up second in the NASCAR season points championship. He had also seen his good friend Cotton Owens capture three victories with David Pearson and Bobby Allison behind the wheel during the season. In all, Ray had witnessed Chrysler products win 36 of NASCAR’s 49 races and win 13 of USAC’s 23 races. Lastly he saw Chrysler driver Al Unser win the USAC Rookie-of-the Year title, this time scoring 11 top tens in just 13 races and finishing fifth in the season points championship. Lastly, one thing that continued to stick out in Ray’s mind was the tremendous growth of Nord Krauskopf’s team under the direction of Harry Hyde. They hadn’t won a race yet, but the team was beginning to jell under Hyde’s guidance of former Nichels driver, Bobby Isaac. Ray knew there were big things in future for the K&K Insurance team.

The year 1967 was a breakthrough season for his 19 year-old son, Terry, who had started his own stock car race team. Terry was the driver, chief mechanic, crew chief and tow truck driver, much like Ray had been when he was 19 years old. After winning quarter-midget championships before he had even reached his teens, Terry clearly possessed the skills needed to succeed as he moved up into a new class of racing. He proved it by running with the leaders in a series of races and winning some trophy dashes during the late season at Illiana Motor Speedway in neighboring Schererville. Then Terry broke through on Labor Day, winning his first stock car feature, a 40 lapper on the half-mile asphalt oval, and yes, it was in a Nichels Engineering built Plymouth, that Terry now owned outright. Up next: More challenges in 1968.