Chrysler’s Stock Car Connection — Part 10

1966 SEASON WRAPUP: Chrysler and Nichels chalk up a remarkable showing with national championships in NASCAR, USAC, IMCA and ARCA.

By Wm. R. LaDow Photos from “Conversations with a Winner— The Ray Nichels Story.”

THE STORY SO FAR

Part 1- Aug. 2013: GM bows out of NASCAR, opening the door for F.R. Householder, Chrysler’s Manager—Circuit High Performance Competition, to sign on Nichels’ Engineering, which formerly fielded race-winning Pontiacs, to become Chrysler’s stock car builder. Part 2- Oct. 2013: Nichels debuts his 1963 Plymouths. Initial testing and competition prove out Nichels designs. USAC drops a bomb. Part 3- Dec. 2013: The Hemi debuts and sends shockwaves through the racing world. Part 4- Feb 2014: The Daytona Firecracker 400, NASCAR’s bombshell and the end of an era. Part 5- April 2014: NASCAR bans the Hemi. Part 6- June 2014: Nichels keeps Chrysler in the game by running other circuits as NASCAR tires to lure Chrysler back. Part 7- Aug. 2014: 1966–Chrysler and NASCAR settle their differences, and Ray Nichels expands his operation with a new factory and new drivers. Part8- Oct. 2014: Chrysler unveils the new Dodge Charger, surprises with the 405-cube Hemi and gets hit with exploding tires. Part 9- Dec. 2014 Chrysler continues its winning ways going into the Spring of ’66 as NASCAR plays fast and loose with the rules.

At the Dixie 400 on August 7, 1966, Junior Johnson showed up with, a bright yellow Ford Johnson’s entry was by no means a normal Ford Galaxie. For openers, Junior had completely restructured the roof of the car. It was apparent that the roof had been cut away, then substantial sections of the roof’s posts were removed and the roof welded back on. In fact, the car’s roof line was reduced in height so much, that driver Fred Lorenzen had to lower his seat in order to see out of the newly sloped windshield. The front fenders of the car seemed to almost engulf the tires and the rear of the car was jacked up higher than any other car in the paddock. Its odd shape seemed to scream out for a nickname. It got one in a hurry, the “Yellow Banana.” Not to be outdone, Smokey Yunick showed up with a black and gold Chevrolet Chevelle that had also undergone some sort of assembly metamorphosis, with the wheels off-center of the car-body’s cutaways, a handcrafted front end and a spoiler built into the roofline.

To the amazement and subsequent anger of the other competitors, both the Johnson Ford and the Yunick Chevy passed NASCAR inspection. The cries of “unfair” could be heard all the way to NASCAR headquarters in Daytona Beach. In the meantime, Cotton Owens’ Dodge was found to have a device that allowed Pearson to lower the front end of his car after the race had started. Owens in a defiant stand against what he believed to be different rules for different race competitors, refused to alter his No. 6 Dodge Charger, as long as Johnson’s and Yunick’s cars were left as is. When told that NASCAR demanded Owens car be “brought up to NASCAR standards” Cotton loaded up his Dodge and left Atlanta in a staggering display of defiance by a team in the hunt for the NASCAR season national championship.

Nichels Engineering was able to pass inspection and qualify for the 400 mile race, with Goldsmith qualifying fourth and McQuagg ninth. The race was a battle to the checkered flag as Richard Petty and his Plymouth got the victory besting Buddy Baker in a Ray Fox Dodge Charger. Mopar entries took the first six sports with McQuagg pushing his Nichels Charger to third place. Goldsmith finished out of the money in 39th spot with a distributor failure.

The focus returned to USAC where Don White and his Nichels team were just starting to come of age. The Milwaukee Mile hosted two races in a row as part of the Wisconsin State Fair festivities. First held was the 150 Miler on Sunday, August 14th. Nelson took the pole and led the chase with his teammate Hurtubise and White in pursuit. All three racers took turns leading until “The Great Dane” charged ahead on the 70th lap. So strong was the Norm Nelson race team that they set eight separate track records during the course of the 150 lap contest. Jack Bowsher, a recent addition to the USAC stable, ran a strong second and White finished third. The following Thursday, the Nichels team came back as focused as ever. Don took the pole in a record time of 35.623 seconds, reaching a speed of 101.058 miles per hour. White then proceeded to outrun the field by margin of 14.5 seconds on his way to his fourth victory of the season. The No. 3 Nichels Dodge Charger led the first 74 laps before pitting. White then regained the lead on the 123rd lap and drove to the checkered flag.

USAC racing resumed on August 26th at the Indiana State Fairgrounds in Indianapolis for the Fifth Annual State Fair Century. Billy Foster, driving a Rudy Hoerr Dodge was the pole winner setting a new track record. The race showed a variety of leaders from Foster, to AJ Foyt, along with Sal Tovella, Whitey Gerkin, and finally Don White. There was high drama on the final lap as Hank Teeters in his ’64 Ford blew an engine leaving a path of hot oil that White promptly drove into, subsequently spinning into the fence killing his engine. But White’s 24 second lead allowed him to get re-started and limp across the finish line for the victory.

2nd place in season point. Billy Foster (L) and Norm Nelson (R) were 3rd and First. Most importantly, Chrysler held 8 of the top 10 season finishers based on owner’s points.

The dirt at DuQuoin was the next USAC challenge on September fourth. Although not the strongest engine in this particular field, White later admitted that the Nichels chassis setup was key as Don took the pole and captured his fourth victory in a row in front of 21,000 fans. But with only three races left in the USAC season, White was still substantially behind Nelson in the season points. Although Don had won seven of the 15 races run, Nelson continued to finish every one of his races within the top five, a testament to the Plymouth pilot’s skill as a driver and mechanic.

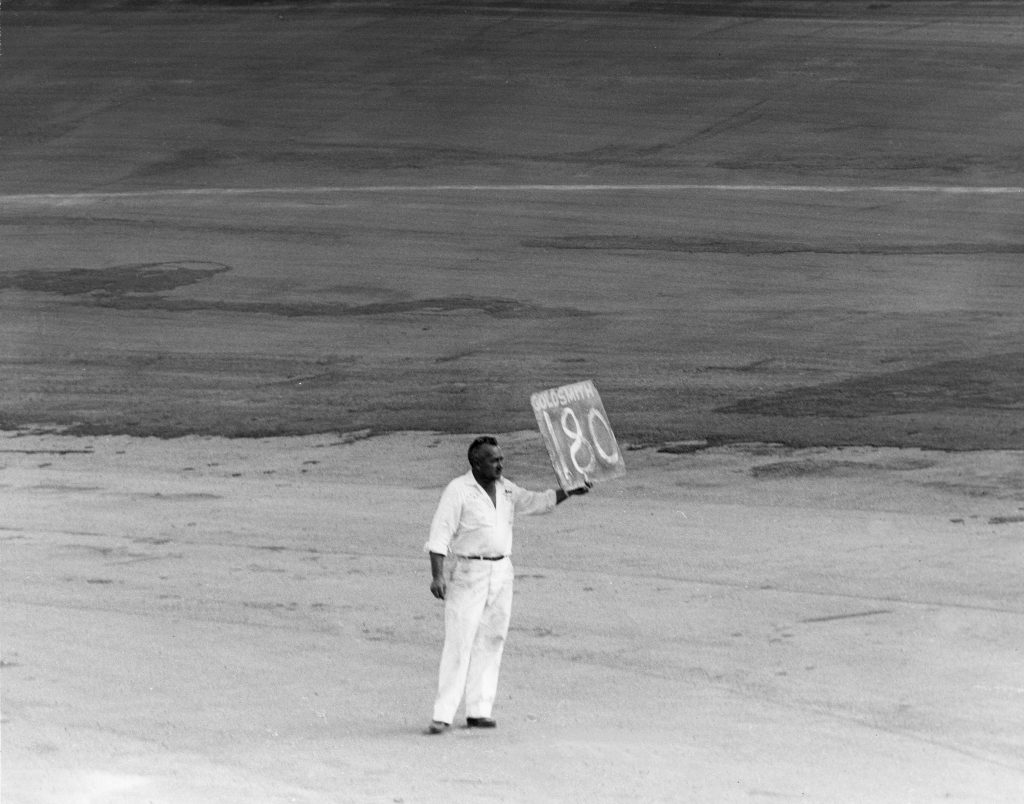

Ray Nichels in the meantime flew overnight to Darlington, South Carolina for the 17th running of the Southern 500. Goldsmith qualified fourth and McQuagg fifth for NASCAR’s traditional Labor Day race. Unfortunately for Goldsmith, due to a traffic jam outside of the track (65,000 fans in attendance), Paul missed the drivers meeting. When the race started, Goldy blew by the field at the green flag and soberly learned what had been the most important subject discussed at the driver’s meeting … “no jumping the start.” It cost Goldsmith a black flag and he never recovered, finishing 16th. The race was marred by eight caution flags, resulting in 80 laps (of the 364 run) under yellow. McQuagg in his Nichels Charger hung tough and finished ninth. The day’s winner was Darel Dieringer driving for old Nichels friend Bud Moore.

Back in USAC, Langhorne was the next stop and Norm Nelson didn’t let up on his run to the championship by taking the pole position for the September 11th race. White charged out to the front at the green flag and battled Nelson and Hurtubise. With Billy Foster in the mix, it wasn’t until the 46th lap that “Herk” took the lead and held it until the 168th lap when White pulled back out front. But on lap 182, the Hemi in White’s Charger let go throwing oil across the track, putting Gordon Johncock into a nasty spin. Hurtubise took the victory and Nelson finished third (with a broken upper control arm on the right front wheel no less.) Don White’s DNF virtually ended his chance for a national championship.

The next week USAC returned to Milwaukee for the final time in 1966 for a 250 miler. Don White took this opportunity to make a statement. Although he appeared to be mathematically out of the running for his second national stock car title, he was by no means through. Norm Nelson started from the pole and took an early lead until White passed him on the eighth lap. Don ran the field ragged leading for the next 73 laps. Then with cautions and pit stops, a myriad of leaders surfaced during the competition. On the 125 lap, White took the lead for good and completed the 250 lap race in just over two hours and 40 minutes picking up a good part of the $26,000 purse. Norm Nelson finished the day in fourth place assuring himself of the USAC season championship.

As the stock car season wore down, Nichels’ NASCAR schedule ended with three races for Goldsmith and McQuagg and two for Don White. On September 25th, Martinsville, Virginia was the venue of choice. On race day, things started fairly well, Goldsmith qualified fifth and McQuagg 11th on the half-mile paved track. But the 250 mile, 500 lap race was another matter. First Goldsmith lost his brakes surrendering on the 229th lap, finishing 27th. Then McQuagg’s steering failed on the 347th lap, giving his an 18th place finish. But the real story was the winning of the race and subsequent disqualification of Holman-Moody’s driver Fred Lorenzen. Beginning at the recent race at Darlington, NASCAR had instructed all competitors to start using the new Firestone manufactured, rubber bladder fuel cell. In the case of Lorenzen, his Holman-Moody team was seemingly able to get his particular fuel cell to hold 1.1 gallons more fuel than his competitors. The result in post race inspection was the announcement that Lorenzen would be dropped to 40th spot and Darel Dieringer given the victory. Once again NASCAR inspection had come under intense scrutiny. Three days later, NASCAR reversed itself and declared Lorenzen the winner, because “There was no indication that the fuel cell had been tampered with.” It was clear that Norris Friel had his hands full with all of the challenges of maintaining some semblance of order in light of the quickly evolving stock car scene.

Meanwhile the USAC season ended quietly on October 9th with Norm Nelson winning the 200 miler on the road course in Wentzville, Missouri. With that victory, Nelson became only the third driver ever to win back-to-back USAC championships, joining Fred Lorenzen and Paul Goldsmith.

With the USAC season completed, Ray Nichels entered his three drivers in NASCAR’s final two races, the National 500 at Charlotte and the American 500 at Rockingham. At Charlotte, Goldsmith qualified seventh, Don White 13th and Sam McQuagg 36th. The real story of the weekend though was LeeRoy Yarbrough in the Nichels-built, Jon Thorne-owned Dodge Charger winning his first superspeedway race. The native of Jacksonville, Florida led 301 of 334 laps, powering past the field in front of 55,000 fans in route to winning a purse of $14,500. It was clearly the biggest win of young Yarbrough’s career to date. It was particularly rewarding for Ronney Householder and Ray Nichels to see the Thorne race team win in such dominating fashion. Goldsmith came in third winning over $4,000. Both White and McQuagg struggled, with Don finishing in 22nd spot with an engine failure. McQuagg suffered the identical fate losing his engine on lap 35, finishing in 40th place.

Although the “American 500” on October 30th at Rockingham was the final NASCAR race of the year, the 500 lapper was by no means a forgotten contest. In the case of Chrysler Corporation, it was clear that the Mopar teams had dominated the superspeedways during the season with Ford Motor Company gaining only one victory to date, Bud Moore’s Mercury win at Darlington. Ronney Householder wanted to keep it that way. Winning this 500 mile race on the banked superspeedway was of particular interest to both automakers. Nichels Engineering started in solid shape with Goldsmith starting in sixth position, Don White in eighth and Sam McQuagg in 11th.

The four hour, 47 minute race marathon came down to the survival of the fittest. In the end, controversy again was the biggest winner. Fred Lorenzen won the race and pulled in to the winner’s circle after leading the final 219 laps. The second place winner was Nichels Engineering’s own Don White. Once again however, Lorenzen did it with unbelievable gas mileage. Immediately following the race, Ray Nichels was pulled aside by Ronney Householder and instructed to issue a protest. Ray approached NASCAR official John Bruner, handing him $100 (the standard fee for filing a NASCAR protest.) Nichels asked that the Holman-Moody Ford’s engine size, car weight and fuel cell capacity be inspected. Ray told Bruner “Lorenzen got over 100 miles on a tank of gas. We get around 80 miles, naturally we’re curious.” Nichels also noted that none of the cars were weighed during morning inspection as is common practice for NASCAR. Hearing this, John Holman pulled out $400 demanding to have the second through fifth cars inspected. So for the next three hours, NASCAR inspectors tore down the five top finishers. But it was to no avail. None of the competitors were to found to be out of compliance and the 1966 NASCAR season finally ended mercifully.

ARCA proved to be another fertile ground for Nichels-built winning carsm here campaigning a Nichels Engineering Dodge Charger in ARCA is Ignatius “Iggy” Katonah.

The 1966 NASCAR National Championship was won by David Pearson. His Cotton Owens built and wrenched Dodges helped David win 15 races in 42 starts earning over $78,000 in purses. It was Owens’ first national championship as an owner. Right behind the team of Pearson and Owens, was independent James Hylton who had battled the factory teams’ toe-to-toe all season. Behind Hylton in third place was Richard Petty with eight wins and 15 poles.

For Nichels Engineering, Paul Goldsmith led the way winning three times with 11 top-five finishes in only 21 races. Paul finished third in purse money winning over $54,000 in just over half the races that Pearson and second place money winner Richard Petty competed in. McQuagg with his Firecracker 400 victory at Daytona and seven top-ten finishes in just 16 races finished 15th in points and eighth in earnings with almost $30,000.

On the USAC side of the ledger, Don White’s performance could only be described as stellar. Don ran 16 races winning eight. He had 11 top-fives, 16 top-tens, along with winning six poles and taking home just a shade under $30,000 in winnings. The difference in Norm Nelson winning the USAC championship versus Don White was that White took Ray Nichels’ marching orders to heart, and either won the race or blew up the car trying. During the course of the season Norm Nelson never finished lower than fourth place while White had the occasional DNF. In addition to Don White’s USAC performance, in just eight NASCAR starts Don had three top-fives and 5 top-tens with total winnings of just under $20,000.

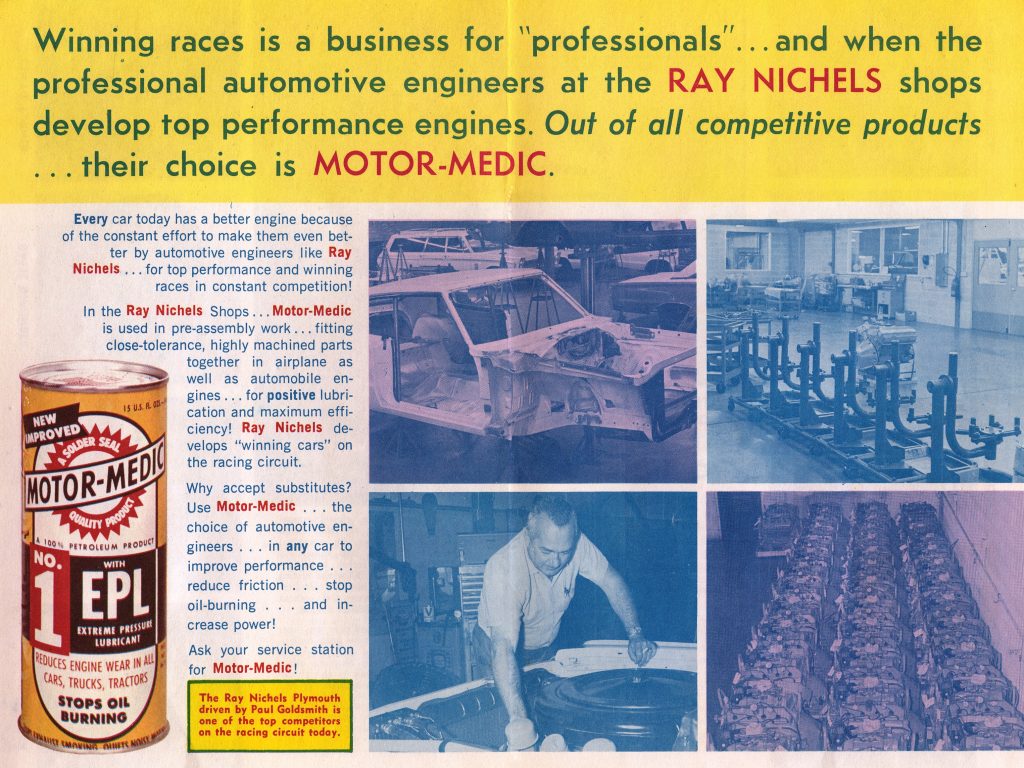

Not only did Chrysler Corporation win national stock car championships in NASCAR (four of the top five in car owner’s points) and USAC (eight of the top 10 in car owner’s points) but they also dominated IMCA (International Motor Contest Association) and ARCA (Automobile Racing Club of America.) In IMCA, Ernie Derr bested fellow Keokuk Komet Ramo Stott for an unprecedented seventh national championship in his 1966 Nichels-built Dodge and Iggy Katona won his fifth ARCA Stock Car Championship on the strength of 11 wins in his 1965 Dodge.

Rookies driving for Chrysler also did well with James Hylton being named NASCAR Grand National Division Rookie of the Year after 20 top-five finishes in 40 starts in a Dodge. The 1966 USAC Stock Car Rookie-of-the-Year was young Butch Hartman, driving his 1965 Dodge to six top-tens in just nine races.

The teams Ronney Householder and Ray Nichels helped assemble for Jon Thorne and Tom Friedkin also proved to be winners on the race track. Lastly, the team of K&K Insurance having used Gordon Johncock and Earl Balmer as drivers, flashed periods of promise during the course of the season.

As the 1966 race season wound down, Ford Motor Company announced they would be investing $10 million dollars (approximately four dollars for every car they sold in the US) in their motorsports programs. In addition to stock car racing and Indy car racing, Ford announced their intention to return to Le Mans and the development of a sports car prototype program.

Chrysler Corporation however indicated publicly that it would step away from corporate sponsorship in stock car racing. This sent a shiver through the racing community for most of the late summer and fall. What Chrysler said and what they were about to do though, were two different things. Changes were coming for Chrysler, but there were only two people who really knew for sure what was about to happen at America’s stock car tracks in 1967. And those people were Ronney Householder and Ray Nichels.