Chrysler’s Stock Car Connection–Part 3

Chrysler, the Hemi and wins.

By Wm. LaDow Photos from the Ray Nichels Archives

THE STORY SO FAR

Part 1: GM bows out of NASCAR, opening the door for F.R. Householder, Chrysler’s Manager—Circuit High Performance Competition, to sign on Nichels’ Engineering, which formerly fielded race-winning Pontiacs, to become Chrysler’s stock car builder. Part 2: Nichels debuts his 1963 Plymouths. Initial testing and competition prove out Nichels designs. USAC drops a bomb.

One of the best hires Ray Nichels ever participate in was the signing of James Mansfield (Jimmy) Pardue to drive Nichels-built Plymouths in 1964. Pardue (here in the #54 Nichels Burton-Robinson Plymouth) participated in 50 NASCAR races in 1964, gaining 2 poles, 14 top fives and 24 top-ten finishes winning $41,597. His season ranking was 5th overall, an incredible effort considering he sadly lost his life during tire testing at the Charlotte Motor Speedway on September 22ndbefore the season ended

Following Ray’s return from the secretly-conducted speed trials for the 1964 season in San Angelo, Texas, Nichels had much to get done. With Tiny Worley managing the car building and engine assembly operations at the Cline Avenue shop, Ray started coordinating the conversion of some of his old Pontiac racing partners to Chrysler products.

Cotton Owens had been the first to make the transition to Dodge in late 1962, and was way ahead of the curve. Outside of Nichels Engineering supplying Owens parts and Hemi engine test data, Cotton was already positioned to go racing. Owens and his chief mechanic Maurice “Pop” Eargle devised a new tool, the rotisserie, that would soon be used in the construction of many a stock car. Eargle started with a lift hoist, added some pipe, channel braces, and bar stock and in the shops of Cotton Owens Garage fabricated the first stock car building rotisserie. This was exactly the type of innovation that Ronney Householder was looking for. It was Nichels’ job to further any technologies that he would witness at the various shops, and with the approval of the Owens, share with the other Chrysler racing teams. Nichels’ role was all about sharing technologies and supplying support for the growing Chrysler effort.

Owens and his driver, David Pearson, were chomping at the bit to get racing in 1964. It was the same situation with Norm Nelson’s team. Nelson and Gerald Kulwicki had gained much insight from racing Plymouths in 1963 and with Nichels Engineering supplying parts and test information; they too were ready to go. The two race teams that Nichels couldn’t convert were Bud Moore and Banjo Matthews. Ford Motor Company already had a one year advantage in ramping up their racing operations relative to Chrysler, as they previously signed the Moore organization to run Mercury Marauders in NASCAR. Joe Weatherly would continue to drive for Moore along with a second driver, Texan Billy Wade. Banjo Matthews was committed to campaigning a Ford Galaxie, signing A.J. Foyt to run Daytona and some other “money” races. The Ford/Mercury racing group also hired Bill Stroppe to campaign a few Mercury Marauders in USAC with Parnelli Jones being their key driver, alongside Rodger Ward and Indianapolis native Darel Dieringer.

Nichels continued to work closely with Ronney Householder to put together some additional Chrysler teams. Gary Bettenhausen, oldest son of the late Tony Bettenhausen, and the 1963 USAC Rookie of the year would return to run a 1964 Dodge as an independent, sponsored by Ron Esserman Dodge, out of Chicago Heights, Illinois. A new team converting to Dodge was Ray Fox and his driver Junior Johnson. For Daytona, Nichels Engineering would supply a Dodge Polara and parts to get Fox’s team up to speed. With Ray Fox’s superior mechanical skills and his ability to manage a race team, there was little Nichels would have to do on that front. The same situation existed with Petty Engineering. Nichels would supply a couple of Plymouth Belvederes, engines and parts. Interestingly enough Petty sought no support from Nichels Engineering publicly. Lee Petty made it clear to Ronney Householder that Petty Enterprises was a closed shop as far as Ray Nichels was concerned. Nichels would have access to the facilities of every other Chrysler race team, but was not welcome to set foot within the walls of Petty Enterprises. Lastly Nichels would hire Jimmy Pardue to drive the Nichels Engineering built No. 54 Plymouth Belvedere. Ray then coordinated Pardue’s driving contract with a sponsorship commitment from Charles Robinson of Burton-Robinson, Inc. of Fairfax, Virginia.

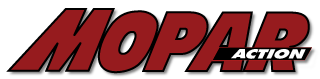

Two of the first cars prepared for the 1964 Daytona 500. The Nichels Engineering Bobby Isaac #26 Dodge and Ray Fox Engineering #3 Dodge driven by Junior Johnson. Both cars were constructed at the Nichels Cline Avenue shop. These two cars won the two Daytona qualifying races prior to the 500.

Nichels then went about the process of forming his own race teams and hiring of drivers. Paul Goldsmith would drive the Nichels Engineering No. 25 Plymouth in 14 or 15 “money” races in NASCAR. For Goldsmith to get clearance to race in NASCAR he was forced to apply for an FIA International license. To do that Paul had to establish legal residence outside the United States, which is exactly what he did. Through a series of legal maneuvers, Goldsmith was able to establish his residency in Mexico City, Mexico. That chore being completed, the only obvious change in Goldsmith’s demeanor around the Cline Avenue shop was that he now answered to the name “Pablo.”

Goldsmith’s prime responsibility for Nichels Engineering, and in effect Chrysler Corporation, would be as a test driver. Paul would play a pivotal role in the evolution of Chrysler car and engine designs. Goldsmith’s NASCAR teammate would be young Bobby Isaac in the No. 26 Nichels Dodge Polara. In USAC, Nichels once again would employ well-respected Indy and stock car racer, Len Sutton in No. 29 Nichels Dodge Polara. For his second new hire for the 1964 season, Ray would take the recommendation of Paul Goldsmith, and hire motorcycle racing star Joe Leonard out of California. Nichels had a real respect for motorcycle riders having had two of the best, Goldsmith and Joe Weatherly, drive for Nichels Engineering. Ray knew that bike riders had a special skill for reading a racetrack. The hiring of Leonard was a solid decision. Nichels could bring Leonard along slowly, working alongside Goldsmith, who had known Joe since 1949. In his time on two wheels, Joe Leonard had won a total of three Grand National Motorcycle Championships in a career spanning nine years. Leonard was also a two-time winner of the Daytona 200, which Nichels took as a sign that Joe would be a driver who would “rise to the occasion.”

In the midst of these projects, Nichels chose to run one more race with his 1963 prepared Chrysler products. The race was held on January 19th in Riverside, California. Listed as the “Motor Trend 500,” it was scheduled to run 185 laps around the 2.7 mile road course. He had Goldsmith in the No. 25 Nichels Dodge and hired past Indy 500 winner Troy Ruttman for a one-on race in the No. 02 Nichels Plymouth. Goldsmith started at the back of the pack in the 44th position, while Ruttman started 17th. Both drivers battled to move up, until Goldsmith lost an engine on the 83rd lap and Ruttman was eventually flagged in 10th place after 177 laps. The day’s racing results however were overshadowed by a terrible loss. Former Nichels’ driver and close friend Joe Weatherly was killed on the 86th lap when his Bud Moore Mercury Marauder struck a retaining wall after losing control coming out of the esses. The 41 year-old Weatherly, had never been comfortable wearing a shoulder safety harness following a roll-over accident some years before. It would prove to be his undoing. Joe had been pushing the Mercury hard, when the car’s brakes began to fail; suddenly it lost traction and barreled into a retaining wall. Later, when the crash’s chain of events was analyzed, it was believed that Joe’s helmet hit the retaining wall hard enough to crack it and end Joe’s life. As bad as Ray Nichels felt, he knew no one could be hurting more from the loss than his friend Bud Moore. Weatherly and Moore had enjoyed back-to-back NASCAR championships and were just starting with a new carmaker and sponsor. There seemed to be no brighter future in racing than the one awaiting Bud Moore and Joe Weatherly. Moore, like Nichels (after losing Pat O’Connor at Indianapolis,) weighed carefully the decision whether he wanted to continue racing as a career. In time Bud Moore, the warrior that he was, soldiered on.

The 1964 Daytona 500 polesitter Paul Goldsmith and his Nichels Engineering Plymouth Belvedere. Goldsmith’s qualifying speed of 174.910 mph substantially bettered Fireball Roberts 1963 qualifying speed of 160.943 mph, shocking the racing world.

Nichels tried to put his grief aside and got back to work. With his Chrysler race team and car building operations now organized, it was time to go stealth. Nichels shut down all public relations and interview opportunities. Just like Ray had done before, in early 1957, he and the efforts of Nichels Engineering seemed to become invisible. Then he went to Daytona and dominated Speedweeks. It was a grand plan.

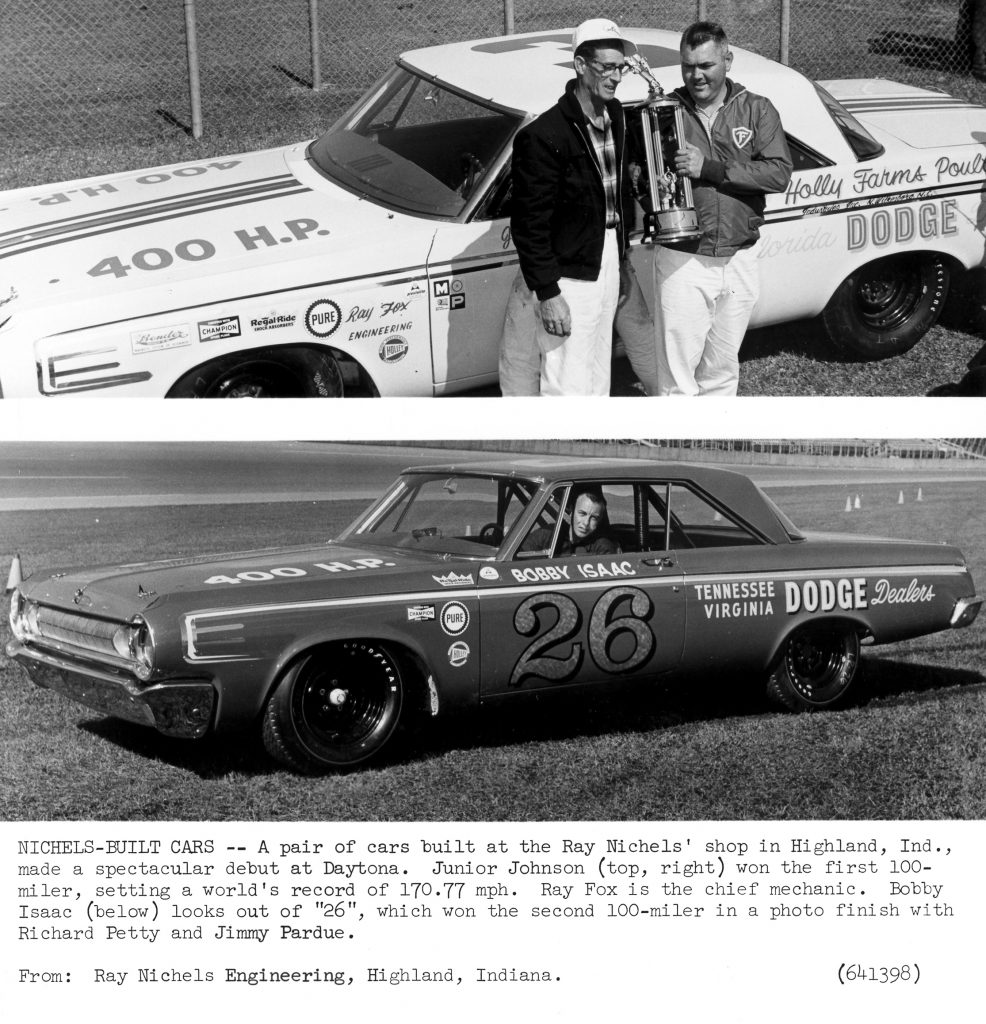

Only Nichels and Householder knew the entire commitment being waged by Chrysler Corporation on their way to the 1964 Daytona 500. Since mid-1963, a handful of men deep inside of Chrysler had been on a mission of secrecy, the re-introduction of the Hemi. This mission involved the Chrysler Highland Park engineering group, the Chrysler foundry in Indianapolis and Nichels Engineering. Nichels Engineering’s performance with the 426 Hemi Super Commando at San Angelo had successfully been a closely held secret. Even when the testing sessions generating speeds of 185 mph, Nichels and his Chrysler partners were able to keep all of the testing information confidential. Up to that point there had only been two Hemi engines that existed and Nichels refused to even confirm the existence of those.

In testing the new engines with blocks being supplied by Chrysler’s Indianapolis Foundry had been performing flawlessly. It was now time to get more built. As production was ramped up, Chrysler engineers were setting up and running the 426 Hemi engines through an endless stream of multi-day runs on their dynamometers in Highland Park, while Nichels Engineering continued to do its own Hemi dyno research at the Cline Avenue shop. Both groups attempted to program the dynos to simulate the demands of a 500 mile Daytona race … high banks, straightaways, pit stops, every possible scenario. Then with the 1964 Daytona 500 just a few weeks away, they uncovered a staggering development. The engines wouldn’t last. They began to fail one after another. The cause Chrysler engineers determined were cracks in the cylinder walls. On January 28th, the conclusion was reached that the only way to make the engines last, was to add stock to thicken up the cylinder bore walls. Deep into the night of February 3rd, working within the walls of Chrysler’s Indianapolis foundry on Tibbs Avenue, coremakers shaved excess sand with custom made templates and then finished the cores by hand. Over the next 24 hours, the cores were dried, placed in the clay-bonded sand molds and cast. Three blocks cast that night would run in the 1964 Daytona 500 just a few weeks away. The foundry continued to make progress, casting better and better engine blocks. The castings were rushed to Chrysler for assembly with cylinder heads that were being cast by Campbell, Wyatt & Cannon Foundry in Muskegon, Michigan. Time was of the essence.

Paul Goldsmith in the 1964 Nichels Engineering Plymouth Belvedere that earned the pole position for the 1964 Daytona 500. Goldsmith shattered the previous year’s pole qualifying record by running just under 175 miles mph.

When Cotton Owen received his first Hemi engine from Nichels Engineering he was heard to say “NOW, we’re gonna go racing.” As race teams began to head to Daytona, several of them were without the new sturdier Hemi engines. Householder promised them all that the new, improved Hemi engines would be there in time to race. But early on in Speedweeks, race teams were forced to use the older Hemis with the flawed blocks. As practice led to qualifying, the word throughout the Chrysler ranks was “conserve.” Householder made it clear that he wanted all of the Chrysler teams to keep the true power of the Hemi engines concealed until race day. The teams quickly learned that the Hemi engines proved to be so powerful that Chrysler race teams didn’t have to go flat out during qualifying to distance themselves from the competition.

Qualifying day arrived with much apprehension in the air. That apprehension was alleviated quite quickly. When it first circled the track for qualifying on February 7th, the No. 25 Nichels Engineering Plymouth Belvedere nicknamed “The Red Rage,” seemed to catapult out of turn four and left in its wake a deafening roar the likes of which had never before been heard on the high banks of Daytona. When qualifying was finished, fans were stunned at what they had just witnessed. Goldsmith, setting a new world stock car record of 174.910 mph, put his stamp on the proceedings by taking the 1964 Daytona 500 pole at almost 15 miles per hour faster than the 1963 Daytona pole winner Fireball Roberts’ qualifying speed of 160.943 mph. It didn’t end there for Chrysler, as Richard Petty qualified next to Goldsmith with a speed of 174.418 mph. This was the fastest front row, for any stock car race, at any track, ever!

It appeared to all concerned that Chrysler Racing was about to perform a superspeedway symphony and the conductor was Ronney Householder.

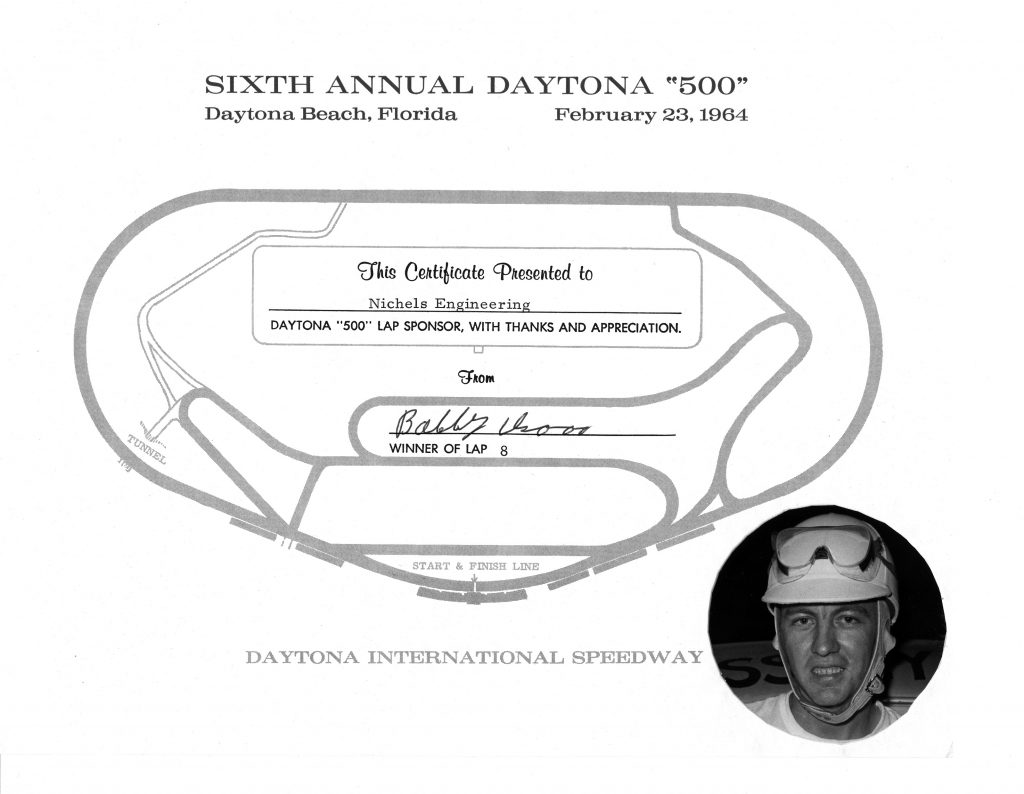

Next on Ray Nichels’ Daytona dance card were the two 100-mile qualifying races on February 21st. Although there had been much talk about the power of the Hemi engine, there were still many disbelievers who felt the new engines didn’t have the endurance to go the distance without failure. The Nichels Engineering fleet of Hemi Chryslers put a dent in that logic in a hurry. Junior Johnson, in his Nichels-built No. 3 Dodge Polara, prepped by master mechanic Ray Fox, won the first qualifier with an all-time Daytona race record average speed of 170.777 mph. Then in the second qualifier, Bobby Isaac in his first start for Nichels Engineering won what was believed to be the closest finish ever at Daytona. Isaac won by approximately 12 inches, leading Chrysler teammates Jimmy Pardue and Richard Petty over the finish line with an average speed of 169.811 mph.

The engine that changed Stock Car racing forever beginning in 1964. The 426 cubic-inch Hemispherical Combustion Chamber Engine … “The Hemi.”

When the dust cleared following the qualifying races, the naysayers could still be heard around the mammoth superspeedway. “The Hemis won’t last,” they said. “There’s no way a new unproven engine can come to Daytona and dominate for 500 miles.” There was even more gossip about the availability of Hemi engines. The speculation in the garage area was rampant. But there was one man who didn’t doubt the possibility of a Chrysler sweep, Ralph Moody. It was Moody, who privately said “Nichels came here in 1957 and no one believed he’d dominate Speedweeks then. Who’s to say he won’t do it again?” Moody was right.

On Sunday, February 23rd, as Paul Goldsmith crossed the start/finish line to take the green flag for the 1964 Daytona 500, he drove squarely through a wall of debris that had come down from the grandstands. Paper cups, hot dog and hamburger wrappers, just about any piece of paper one could imagine ended up on the track as the field roared through. Goldsmith led the first lap. Then Richard Petty, Bobby Isaac and Goldy each took turns leading until the 51st lap. Following a caution for David Pearson’s blown tire, Richard Petty pulled back into the lead. Goldsmith began to have problems with his Plymouth overheating and during an unscheduled and lengthy pit stop his Nichels’ pit crew found out why. Some paper food wrappers had gotten under the car’s grill and blocked part of the radiator. While the field was pulling away, Nichels’ pit crew was pulling trash from the front of the pole sitter’s car. In the end, it was Petty who grabbed the victory. He was chased across the finish line by Jimmy Pardue and Goldsmith for a Plymouth sweep of first, second, and third places. Unbelievably, the 426 Hemi engines that carried these Nichels-built cars across the finish line had their blocks cast by Chrysler’s Indianapolis foundry only 14 days prior to the race. The secret mission that had started in mid-1963 involving the Chrysler Highland Park engineering group, their foundry in Indianapolis and Nichels Engineering had been accomplished.

Every stock car race fan in America now knew there was a new sheriff in town and his name was Hemi.

As the Chrysler faithful celebrated, the Nichels Engineering team headed back to Indiana to continue in their quest to make Chrysler the dominant race car in America.

Goldsmith and Isaac had gotten their season off to a great start at Daytona. With Goldy coming in third in the 500 miler and Bobby winning a qualifier and then finishing 15th in the big race (because he ran out of gas), Ray was confident that his team was coming together. The next race for the Nichels NASCAR team was on March 22nd at Bristol, Tennessee. The 500 lap race on the steeply banked half-mile track kept the entire Nichels team working endlessly. Goldsmith garnered a third place finish, while Isaac finished 27th after losing a rear end.

Two weeks later the Nichels NASCAR team was in Hampton, Georgia for the Atlanta 500. Goldsmith qualified third and Isaac sixth with both cars running extremely well. Since its opening in 1960, the 1.5 mile high-banked Atlanta International Raceway had gained a reputation as one of the fastest tracks on the NASCAR schedule. This race would be no exception. Goldsmith starting in the second row wasted no time passing pole sitter Fred Lorenzen on the first lap. Paul pushed his No. 25 Nichels Hemi Plymouth hard as he established himself as the man to beat. Staying right behind Paul was his teammate Isaac in his No. 26 Nichels Hemi Dodge. After leading the field for 55 laps, going into the third turn, Goldsmith’s right front tire exploded, throwing his car violently into the outside guard rail. Traveling over 140 miles per hour, Goldy’s car started to roll as if it was about to topple over the guard rail and out of the race track completely. At the last moment, the car flipped over onto its roof and began to slide through the third turn. Still going almost 140 miles an hour, Goldsmith upside down, and suspended by his shoulder harness, was not only sliding forward through the turn, but now was sliding down the race track toward the infield, just missing Fred Lorenzen who roared by. Finally the Nichels Plymouth ground to halt inside the fourth turn and moments later Goldsmith emerged uninjured, his only problem being that he was so disoriented he thought his car had in fact tumbled outside of the speedway. Lorenzen was the race winner, saying during an interview following the race, that when he saw Goldsmith, upside down, sliding toward him, he thought he was a goner. After the contest in which the other Nichels driver, Bobby Isaac finished a sold second place; Householder humorously chided Goldsmith telling him “if you would have taken Lorenzen out on your way by, your teammate Bobby would have won the race.”

In the meantime, the Nichels USAC race season was just beginning, with a 150 miler at Langhorne on April 26th, followed by a 300 miler at Indianapolis Raceway Park on May 3rd. The Nichels team of Len Sutton and Joe Leonard got off to a rough start with mechanical difficulties plaguing both drivers in both races. Jim Hurtubise won at Langhorne driving a Norm Nelson Plymouth, while Fred Lorenzen won the Yankee 300 at IRP in a Ford. That sent the Nichels team back to the NASCAR circuit with the May 9th running of a 300 miler at Darlington Raceway. Both Goldsmith and Isaac qualified mid-pack and didn’t have much to show for the day’s work. Paul finished the race running in ninth and Bobby’s wreck finished his day in 27th spot.

Nichels Engineering sponsored many on-track activities, which were even more gratifying when one of their own drivers was the winner.

The next stop on the NASCAR schedule was the World 600 at Charlotte on May 24th. Goldsmith, by virtue of his running in the Indianapolis 500 every year since 1958, had never had the opportunity to run the 600 mile race at Charlotte. Though his USAC suspension banned him from running Indy, at least NASCAR provided a “money” race for him. The Nichels Engineering cars were ready to run by the time they got to the Charlotte Motor Speedway and showed it by qualifying Isaac in third starting spot and Goldsmith in fourth. With Nichels cars making up the second row on the grid, spirits were high when the green flag fell. The Nichels-built Mopars of Jimmy Pardue, Paul Goldsmith and Bobby Isaac broke free from the field early and it looked like the Nichels optimism was more than warranted. But that optimism suddenly turned to horror during a seventh lap collision. Former Nichels Engineering driver Glenn “Fireball” Roberts tried to avoid the spinning cars of Junior Johnson and Ned Jarrett, Roberts’ Ford hit an uncovered abutment on the inside retaining wall, flipped upside down and caught fire. Roberts, who was severely burned, was airlifted to Charlotte Memorial Hospital where he was listed as “extremely critical.”

Although the race was restarted, many drivers couldn’t erase the image of Roberts’ Ford burning on the track. The crash once again raised the question that seemed to be surfacing over and over again. “Were the speeds climbing out of control? Were these new, more powerful engines, just too powerful for safe racing?” The pole sitter for this particular race was Jimmy Pardue with a track record 144.772 mph for the 1.5 mile high-banked track. It seemed every race; every week brought a new track record. Was it possible to be going too fast?

When the World 600 continued, the Nichels’ Chryslers were leading the way. Pardue led the first 33 laps. Then Isaac led for nine laps with Goldsmith leading the next 15. LeeRoy Yarbrough driving the No. 03 Ray Fox Dodge also led several laps. David Pearson and Buck Baker driving Chryslers also got into the act. It was all Chrysler, all day. But the toll on the equipment began to show. First it was Bobby Isaac in the Nichels No. 26 Dodge, whose engine self-destructed, tearing an engine mount free. Then Jimmy Pardue in the No. 54 Burton-Robinson Plymouth blew its engine. In the meantime Goldsmith took the lead. He led laps 80-121, led again from lap 148-188, finally leading laps 233-253. That’s when Paul’s engine came apart too, and finished Goldy’s day. Chrysler finished the afternoon standing on the podium though as Petty Enterprises’ Jim Paschal and Richard Petty finished in first and second.

Although the racing world may have viewed the Nichels performances as missed opportunities, the reality was Goldsmith, Isaac, Sutton and Leonard were doing exactly what they were paid to do. Run hard, run up front, punish the equipment and if they were going to make the equipment fail, they were to be in the lead when they did it. The mission of Nichels Engineering was to make Chrysler race cars and racing parts better by forcing them to fail, so they could be re-engineered and improved. The team at Nichels Engineering had a more important calling than winning individual races. The team at Nichels Engineering was responsible for making all Chrysler racers better at what they did, by providing them world-class race-tested equipment.

Due to Paul Goldsmith’s ongoing battle with USAC, he and Ray Nichels weren’t present for the 48th running of the Indianapolis 500 on May 30th. It turned out to be a blessing that they didn’t compete in the race. This year’s 500 was marred by a terrible accident that cost the lives of Eddie Sachs, driving a Ted Halibrand-Ford rear-engine Shrike and Dave MacDonald in a Mickey Thompson Ford. It was probably the first occurrence ever of a “real-time” eulogy being delivered during a race. In this case it was Indianapolis 500 Radio Network’s Sid Collins who so eloquently reported on the loss of Sachs. The only positive aspect of the day for Ray Nichels was learning that one of his favorite drivers, A.J. Foyt, had won his second Indy 500 in a car partially owned by Ray’s old employer, William Ansted.

As June began, the Cline Avenue shop was busier than ever, working sixteen hours a day, seven days a week to keep up with the rapidly growing stock car business. Nichels Engineering had to coordinate their participation in three separate races over the next month. First was the upcoming Dixie 400 at the Atlanta International Raceway on June 7th. Then the USAC stock car schedule called for the Continental 250 to be held in Castle Rock, Colorado on June 28th. After those races were completed, the entire Nichels Engineering stock group headed to Daytona for the Firecracker 400 on July 4th.

Well-respected IndyCar driver Len Sutton continued to drive Nichels stock cars through 1964, finishing in the top five in over half of the races he competed in on the USAC circuit. He finished the season in the top ten in points.

Goldsmith’s and Isaac’s Nichels racers were shipped south to Hampton, Georgia for the 400 miler at Atlanta International Raceway. Both cars did well during qualifying with Paul in the second row and Bobby in the fourth row. Junior Johnson, who had left the employ of Ray Fox after the April 19th race at North Wilkesboro, took the pole at just a shade under 146 miles per hour in the No. 27 Banjo Matthews Ford Galaxie. Once again it looked like the mile and a half Atlanta track was going to offer a speed fest for the NASCAR fans in attendance.

As Ray Nichels and his team spent their time in the track garages on Saturday, June 6th preparing for Sunday’s race, a tragedy took place over 700 miles northwest. Ray Nichels’ life-long friend and racer Johnny Pawl had placed a phone call from his shop in Crown Point, Indiana, where he was rebuilding a couple of Kurtis-Kraft midgets, to Nichels Engineering’s Cline Avenue shop talk to Tiny Worley. As it was Saturday, both Pawl and Worley were trying their best to get their day’s tasks completed in an attempt to find a little free time for the evening. While Pawl was speaking to Worley, the phone line suddenly went quiet, followed by some distant yelling. Johnny yelled to Tiny in an effort to find out what was happening, but Tiny couldn’t answer. At that moment, a massive heart attack silenced 45 year-old Dale “Tiny” Worley forever. As was the custom, Tiny wasn’t pronounced deceased until his arrival by ambulance at St. Catherine’s Hospital in East Chicago. But those in the Cline Avenue shop knew that when Tiny was stricken, he was gone in an instant.

When Nichels got the call, he couldn’t believe the news. Tiny Worley had built race cars and traveled the racing circuits with Ray since 1940. Whenever Ray had been forced to work through the terrible loss of friends like Pat O’Connor, Doc Hazinski, Joe Weatherly, or a family member like Ray’s brother Roy and his parents Gladys and Rudy, the one constant outside of his wife Eleanor, had been Tiny Worley. The loss of his friend and one of the cornerstones of Nichels Engineering was almost too much to bear.

The Nichels NASCAR team completed their task at hand in Atlanta with Goldsmith finishing third and Isaac ending in seventh. The Nichels team then headed home to bury one of their own.

Dale Edward Worley was laid to rest on Tuesday, June 9th in the Lowell Cemetery in Lowell, Indiana. He left a wife Barbara, a daughter Lynn Ellen and two sons, Douglas and Michael. He also left a legacy as the best friend a guy could have. For Ray Nichels, life from now on, both personally and professionally, would never be the same.

At the Cline Avenue shop, there was a consensus; Tiny Worley was irreplaceable. The only way to keep the operation running was that members of the Nichels Engineering team: Ralph Knopf, Andy Burch, Minnie Joyce, Jerry Govert, Manfred Hodge, Cecil Van Horssen, Don Asbey, John Kammer, John Johnson, Dave Hilman, Terry Jones, Jim Hanson, and Mike Marozich along with some others had to step up and accept additional duties across the board. Ray was traveling non-stop and unbeknownst to others in the organization was working on another proprietary project that was on a strictly need-to-know basis.

It was time to get back to racing. Continental Divide Raceway, located 25 miles south of Denver, near the town of Castle Rock, Colorado was the third stop on the 1964 USAC stock car schedule. The 2.8 mile paved road course contained 10 turns. Nichels had both Len Sutton and Joe Leonard entered in the event labeled as the “Mile High 250.”

In front of 11,000 fans, 17 other cars challenged the pole sitter Parnelli Jones in the No. 15 Stroppe Mercury Marauder, but no one bested him. The Nichels mounts were plagued by transmission troubles all day. Sutton manhandled his Dodge Polara until the 26th lap when he was forced out of the race. Leonard, in only his third USAC stock race, led early, but also began to experience transmission problems, running without fourth gear for most of the race. Amazingly Leonard was the only driver to really challenge Jones early in the race and held on for third place, right behind Norm Nelson.

Next stop, Daytona.