1959 Imperial Speedster

A snazzy luxo-sport Vette and T-Bird stalker in the Exner style of design.

Story and photos by Paul Stenquist

It was several years ago that Murray Pfaff and his father peered into the dark recesses of a crumbling carriage house in Sackets Harbor, New York, and saw what appeared to be the shrouded remains of an automobile. Venturing inside, with an eye on the building’s sagging roof, they pulled back the tarp. Dust filled the air, and rats raced for cover, but soon the prize that had been buried decades before stood naked to the world.

Murray Pfaff invested a huge amount of time and money to create the Imperial Speedster that Chrysler should have built. No, he’s not afraid to put the pedal down and smoke those expensive tires.

Â

Because the forward half of the front door is joined to the back half of the rear door, front and rear body sections mate perfectly.

It was the jet-age sports car that Chrysler designer, Virgil Exner, had envisioned. The car Exner had created in his mind but, according to all historical records, had never committed to sheetmetal. The car meant to give Corvette and Thunderbird a run for their money: the 1959 Chrysler Imperial Speedster.

The faux spare tire on the deck lid was removed when the panel was shortened and narrowed, then welded back in place.

The Speedster, you see, was a product of Murray’s imagination, an artful concept created by a talented designer who had a fervent desire to build the car that Chrysler didn’t build, the car that Chrysler should have built. The car that Murray believes Exner might have built had he been given the go ahead.

Although all the pieces of the legendary sports car were found in that carriage house, there was something about the machine that wasn’t quite right. It was much longer and wider than it should have been. It had four doors and a steel roof. It looked exactly like a full-size 1959 Imperial, a noble brute of a machine but no sports car. But when the dead Imperial’s shroud was pulled back, Murray Pfaff saw an Imperial Speedster.

The custom instrument faces were designed by the owner. The gauges were rebuilt and refaced by New Vintage Instruments. The tach cup was cobbled from a ’39 Chevy taillight and ’59 Chevy instrument bezel. The steering wheel is from a ’60 Imperial with a center section designed by the owner.

Â

The Speedster, you see, was a product of Murray’s imagination, an artful concept created by a talented designer who had a fervent desire to build the car that Chrysler didn’t build, the car that Chrysler should have built. The car that Murray believes Exner might have built had he been given the go ahead.

The waterfall between the seats and the center console are fiberglass. The chrome trim on the console came from the Imperial’s rear doors. Window switches are hidden under a sliding door.

On the day Murray uncovered that Imperial, the sports car version of a jet-age classic had already migrated from his vivid imagination to paper, as a dimensionally accurate rendering of what the car should be. Channeling Virgil Exner, he decided an Imperial Speedster should be much more than just a shortened, narrowed version of the full-size Imperial. It had to be proportionally exquisite. It had to be the kind of visually stimulating machine that old Virg would have built. That meant the Imperial body had to be carved into 46 major and numerous minor pieces, and then reassembled with precision.

“I will be the first to admit that drawing a cool little car and building one are two completely different things,” says Murray.

Dayton Wire wheels sport Lamborghini Atlas Orange paint and mount Goodyear F1 GS-D3 rubber.

Â

No doubt. Committing that drawing to sheetmetal and fitting it with the kind of running gear that a contemporary version of an Imperial should have ultimately required more than 10,000 man-hours over four years. Ten of Murray’s friends pitched in on the project, sacrificing nights, weekends and marriages to do the job Chrysler didn’t do.

Carving a svelte and sexy sports car out of that Imperial land yacht was the biggest challenge. After mounting the mammoth Imperial body on a jig that could be adjusted for length and width, the sectioning began. First, the roof came off, and then doors were crafted using sections of the front and rear doors. Next, 36 inches of length was cut from the center of the body. The jig was adjusted to bring the two halves together, and they were welded. That technique was employed over and over as 8 inches of width, 11 inches of rear overhang, 11 inches of quarter panel, three inches of front wheel well and three inches of front clip were removed. With the car welded back together, it was cut in half again to remove another 3-inch section. The hood and deck lid were shortened and narrowed proportionately. Bumpers, splash pans, door jams and other parts were cut, welded, finessed and finished.

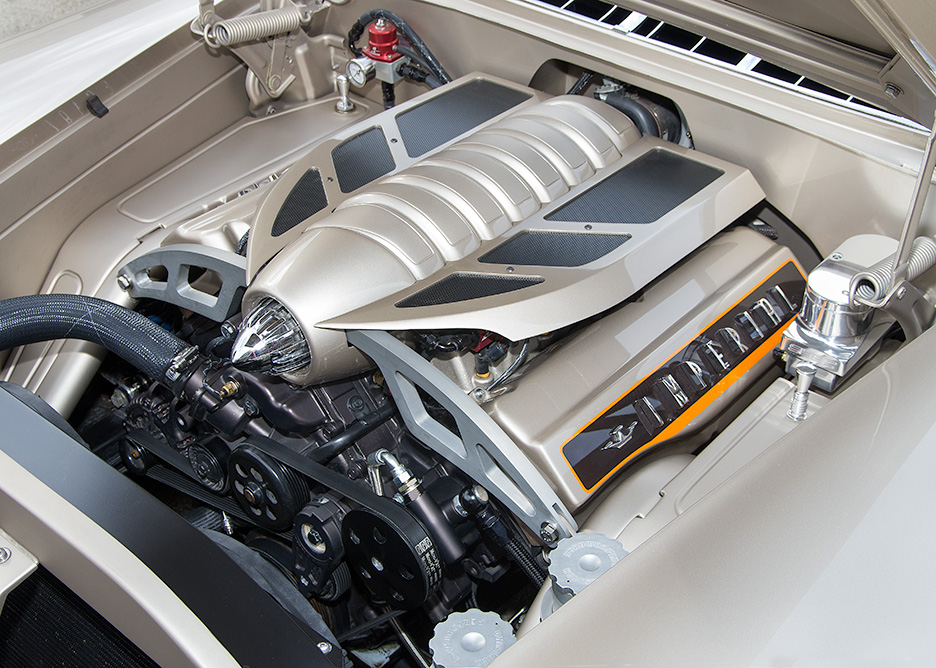

The 425-horsepower 6.1-liter hemi is topped with an owner-modified intake. The unit is reversed and air enters through a K&N filter at the firewall. The valve covers, which began life on a vintage 392 Gen 1 hemi were fabricated by Steve Langdon. The lettering on the covers once rode on the front fenders of the Imperial sedan.

But the attention to detail didn’t stop with mere finesse and flawless execution. To perfect the fascia, the undersides of the front fenders were trimmed, so the headlight buckets could be separated from the grille and moved up into the fenders. A pair of grille bar ends with integrated LED turn signals were designed and built. The A-pillar was modified and chromed; eight crown emblems were plated in 24-carat gold. “Speedster” badging was designed and manufactured. And a curvaceous competition-style windshield was formed of polycarbonate, using a fiberglass mold made using the original Imperial windshield.

The end product is a work of art.

But Murray wanted the Speedster to be more than sculpture, so a chassis was constructed using the forward half of a Schwartz Performance G-Machine frame coupled to a narrowed Viper independent rear suspension system. The wheelbase was set at a taut 91 inches. RideTech springs and shocks provide front suspension. Steering is by means of a Unisteer Mustang quick ratio rack and pinion. Raybestos NASCAR Super Speedway 4- piston calipers were mounted front and rear on slotted rotors.

A set of wire wheels from Dayton mount 225/45zR/17 Goodyear F1 GS-D3 rubber up front and 275/40ZR/18 boots in the back. Bet you didn’t know Goodyear made those high-zoot tires with whitewalls, did you? They don’t. Diamondback Classic Tires of Conway, SC applied the retro white stuff.

Back in the day, a sports car version of the Imperial probably would have been fitted with the 318. That ancient anchor could never deliver the kind of muscle Murray must have envisioned when he fitted his speedster with that big gum, so a 6.1 SRT Hemi crate motor was purchased and fitted with an Aeromotive fuel system. Steve Langdon, who did much of the body fabrication and welding work, stretched, widened, shortened and filled some Gen 1 hemi valve covers to give the powerplant a period feel. Extensive reworking of the intake housing, which is reversed for both esthetic and practical reasons, adds jet-age pizazz.

A ten-inch Alpine subwoofer resides in a custom trunk enclosure crafted by Street Legal Customs. Chrome plated luggage strips over BMW square-weave carpet add an elegant touch. Imperial Speedster badging takes it right over the top – in a good way.

The exhaust system combines 2.5-inch polished stainless pipe with Flowmaster Hushpower mufflers and reworked Mopar headers.

Backing the engine is a Phoenix Transmission Products PT 518 SS four-speed automatic with a 2500-rpm stall speed 11-inch converter. Gear changes are accomplished – as they should be in a 1959 Chrysler product – by means of pushbuttons. A 2.45:1 first gear ratio coupled with a 3.07:1 final drive gives the Speedster plenty of squirt, while a .69:1 top gear makes it an efficient highway cruiser.

After we had shot the car at the old Packard proving grounds in the Detroit burbs–a place steeped in fifties lore and dreams of what might have been–Murray took us for a ride around town. On the torn up pavement of the old proving grounds, the firmness of the suspension tune was obvious, but no rattles were heard and no cowl shake observed. On the open road, the car rode beautifully. When Murray planted his foot, the hemi sang in a deep baritone, and the Speedster flew like a Speedster should.

Having ridden in and driven many custom-built one-offs, we were impressed. This car had the manners and performance of a multi-million dollar factory effort, an engineering achievement that is rare in the hot-rod ranks. And testimony to the skill and commitment of Pfaff and friends.

“Before I started this project I had no idea of the commitment it would take to complete it, said Murray. “That was probably a good thing.”

Virgil Exner would probably agree.

An interesting example of “might have been”.