Missile Madness

The rise and fall of Chrysler Pro Stocks

By Dave Rockwell Photos from the Ramchargers Archives

Our final excerpt from Dr. Dave Rockwell’s groundbreaking new book: WE WERE THE RAMCHARGERS (available from SAE International or Amazon) provides insiders perspectives on the birth of Chrysler’s Pro Stock program. Springing from a wealth of knowledge garnered from a decades’ worth of hard knocks and winning, several Ramchargers were charged with reuniting Chrysler’s drag racing program with showroom relevance. Growing concerns for their funny cars’ safety, expense and marketing value, inspired a pivot to a more production-car DNA — based program.

After years of competing at drag racing’s highest levels, the Ramchargers, then largely comprising Chrysler’s Race Group, wanted to do something special. Starting with Ramcharger Dick Maxwell’s inspiration for building the “ultimate Super Stocker,” the 1968 Hemi Darts and Barracudas were the shining outcome. As Maxwell proclaimed in 2005, “To this day they race in a class by themselves.” Immediately embraced for their brutal performance potential in 1968, the Hemi A-bodies greatest impact would be in serving as launch platform for Chrysler’s Pro Stock program. The following is an excerpt from Chapter 11, “Grabbing a Higher Gear”.

The ’68 A-bodies (Barracudas and Darts) were without peer. And, with drivers like Ronnie Sox they would dominate in spite of NHRA’s increasingly frustrating handicap system. By 1969, promoters and racers had begun to take matters into their own hands by staging heads-up match races between the increasingly popular Hemi A-bodies, big block Camaros and Boss 429 Mavericks. In a display of uncharacteristic adaptability, for 1970 NHRA established a new category for these cars–Pro Stock.

Unfortunately, budget reductions were closing the fabled Woodward Garage, forcing a new plan of attack. Tom “The Ghost” Coddington explains, “We didn’t want to come back into Engineering. That was too stifling with the union and all. So Cahill put together a contract with Teddy Spehar who sold his gas station and went out and rented a series of interconnected shops in Royal Oak. Teddy had raced for us back in the Super Stock program and developed a reputation for a guy you would want to be doing that kind of work–highly capable, congenial and honest. The objective was to provide a development capability for a Pro Stock program.”

But, the mule car this time would also have to earn its keep on the dragstrip. ‘The Ghost’ continues, “At that point everybody was building their own car, and we needed to establish a proper way of doing it. You couldn’t tell them all to come to our tests, but you could take a car to the race track and have the racers see how it worked. Tom Hoover also felt if we put that much money into a car, we had to get some good out of it at the track.”

Dick “Broom” Maxwell laughs, “I used to refer to it as Hoover’s personal racecar.”

Coddington continues, “Sox and Landy were stretched to the limit with their traveling clinic programs, so it was impossible for them to do development work. What we could do with the Missile program was to take responsibility for engineering development out of their hands and pass the information along to their primaries back at the shop, like Jake King and Mike Landy, to keep their racecars up to snuff.”

Hoover reiterates, “I believe one of the reasons for Sox’s success was they raced so much, they just did exactly what we told them to do while Landy liked to experiment more, and as a result was often a tenth or two off the pace.”

But, Hoover explains the most compelling need for a test car: “Here we found ourselves with very few people competent on the four-speed manual transmission. A lot of our heroes had cut their teeth on automatics, while the enemy was running manuals, and the only real competent person we had was Ronnie Sox. So the initial function of the Missile program was to make the Clutch Flight competitive, so somebody like Dick Landy could be successful. The first year of the program was spent on iterations of the Clutch Flight including a secret six-speed version. B&M was instrumental in putting together the hardware, which allowed us to run two transmissions, nose to tail. An awful lot of effort went into that. Unfortunately, it had several adverse impacts on the behavior of the car. It made the car heavier, increased rotating inertia in the driveline between the engine’s crankshaft and rear axle, as well as hydraulic losses canceling out advantages of a wider variety of gear ratios through the drag cycle.

Dick Oldfield who worked for Teddy Spehar on the program also explains, “The Torqueflite was saddled with a 2.45 low gear which we compensated for with a heavy flywheel, which wasn’t ideal.” Still, the car managed to qualify First on several occasions acquiring a reputation as the fastest Pro Stock in the country.

Hoover continues, “We were never able to convince enough of our heroes to use it, so after a year or so the Missile simply became the development car for Pro Stock. We thought, okay we’re going to have to support the program and we need a four-speed manual driver to run our test car.

That’s when we got Don Carlton who had been involved with Sox and Martin. He was an excellent driver, probably second only to Ronnie Sox in our group. Ronnie was simply in a class by himself. I used to say if we had to race the Russians for anything, I’d want Ronnie Sox driving and Teddy Spehar building the motors. Then you might have had proplr like Butch Leal, Herb McCandless, Arlen Vanke and some others. Landy was pretty challenged by the manual transmission, and generally spent too much time declutched.”

Hoover continues, “A critical aspect of our program was putting together the hardware that would allow us to evaluate things like the six-speed. The instrumentation package we used was developed by Chrysler’s Redstone Arsenal people, in Huntsville, Alabama for gathering data in NASCAR. Ron Kellen, an engineer who came north with it was a huge help. It had eight channels that could give you information on tape about the drag cycle, including things like engine speed, clutch speed, propeller speed, acceleration and so forth. It was particularly helpful with the Clutch Flights in documenting how the clutch behaved to translate the engine’s inertia, when the clutch was engaged into the cars forward motion. Very critical. We also were developing “correction factors” involving engine intake air temperature, track temperature, barometer, humidity and so forth, so we could reliably correct runs from morning to evening.”

Tom Coddington explains a key transmission development: “We came up with a new design of the internal shift mechanism for the A833 four-speed. We essentially removed the synchronizers and then ground every other tooth off the gears and their splines allowing for easier shift engagement. It actually was a concept developed for us by the BRM Formula 1 group and their technical director Tony Rudd, who Cahill had contracted for consultation work on some of our projects. We adapted what they had come up with to our parts and called it the “slick shift” (“slick” was Ramchargers-speak, for “good”). It really took away the headaches.”

From the Missile program flowed a number of Pro Stocks engineering foundations. Tom Hoover touches on a few: “In 1971, we decided hood scoop design merited setting aside a couple months of the Missile group’s time and we made a winter trip to Lakeland Florida to test. I knew enough about piston engine aircraft aerodynamic development in the Second World War to realize even though something looks intuitively right, it may not be so.

To that point, we had just kludged up what we thought a hood scoop should look like, pointed it forward and went ahead. We basically tried everything we could think of and it turned out the airplane people were right–particularly the Germans. We found you really need to bleed off the layer of air between the body and scoop to make sure the air that’s coming into the scoop itself is not part of the boundary layer. The boundary along the hood’s surface is turbulent, gradually going slower closer to the surface, so you don’t get a pressure head out of it. Our original version had a ramp running up to the inlet. But once we knew what we were doing, we came to realize that simply fed the boundary layer right into the scoop entrance. What you really want to do is get rid of that ramp and bleed the boundary layer off to the sides and underneath where the air actually enters, hence the snorkel design. Unfortunately, although our guys had it for a few months the enemy was quick to copy. They could walk right up to the car and measure it. And they did.”

Engine development proceeded with Ramcharger John Wherly slipping the low-priority Pro Stock dynamometer work in between NASCAR responsibilities at Engineering, and later in California by Bob Terozzi. Hemi cylinder head development progressed through five stages, from D1 through D5, with the D1 version being the original 1964 head and the D5 developed in consultation with Harry Westlake, featuring a larger 2-3/8″ intake valve and untilted combustion chamber.

Hoover states, “The D4’s made the most power and performed best in the Missile with the intake side being a D1 or A990 with a higher round exhaust port.”

Another innovation was the twin sparkplug head initially developed in consultation with the BRM group. Hoover elaborates, “BRM found a big gain, maybe 20 HP at high speed. We found after developing the twin plug it wasn’t that much different. It did help the engine behave better by keeping the sparkplugs lit during the staging phase of the drag race. On rare occasion if detonation occurred, it could also break the nose off the porcelain of one of the sparkplugs, messing up the exhaust valve seat. In the end, we decided positioning a single plug in the “B” position at 37° advance, as opposed to the twin plugs 33°, was optimal while removing some weight from the front wheels.”

A dry sump oil system was also evaluated, Hoover concludes, “The dry sump did not go any faster than the deep pan, but we did break a belt and replaced some bearings. Properly done, a deep wet sump is lighter and you don’t have to drive the scavenge pump and it goes as fast.”

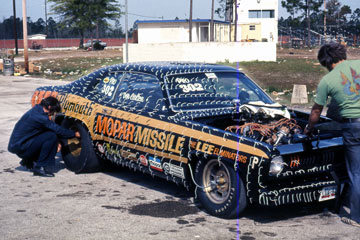

With regard to suspension development, the 1970 and ‘71 Missiles essentially used the same race suspension as the 1968 A-body cars, followed by the introduction of the 4-link in ‘73. Hoover adds, “I’d say the most interesting thing in ‘71 and ‘72 was to sort through how to optimize the wheelie bars. The first wheelie bars were simply suspended from the rear bumper–just metal posts. We then attached them to the rear suspension and began evaluating putting the suspension on the wheelie bars to adjust the spring rate as they hit the ground. The ultimate configuration involved some spring preload and deflection, so they didn’t contact the ground in a discontinuous manner.”

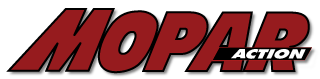

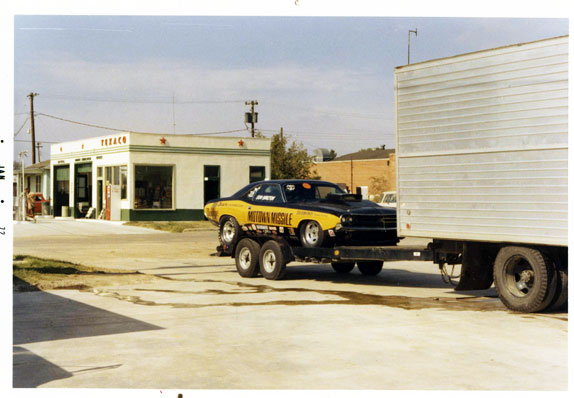

In a Trivial Pursuit gem, the Motown Missile actually owes its name to none other than Arlen Vanke Esq. of Akron, Ohio. First used in reference to another Spehar Dodge race car, it was requisitioned for the nameless Engineering Pro Stock test car. Tom Hoover picks up the story,”

“After while,” relates Hoover, “I began getting some nasty letters from Motown Records’ Barry Gordie. It seemed weird they wouldn’t appreciate us helping to make them even more famous, but they didn’t. So the first A-body–our ‘73 Duster, became the Mopar Missile.”

With Ronnie Sox leading the charge, the Pro Stock program’s fruits were overwhelming, winning most of the NHRA Pro Stock races in 1970 and ‘71. Dick Maxwell recalls, “Most of the NHRA division directors were basically Chevy guys and they put a lot of pressure on the home office and Wally Parks to come up with a way to make us stop winning. I can tell you, there were damn few Mopar enthusiasts among them.

Tom Coddington elaborates, “Chevy’s corporate position was that they weren’t involved. They actually were. They had very active programs and Hoover always felt they spent more money than we did. They were always at the races incognito, but we knew who they were because they were the same guys that had been there in the 1960s and ‘70s. I always thought they must’ve been jealous of us because they couldn’t be out in the open like we were.”

Tom Hoover continues, “It finally got to a point where NHRA told Chevrolet Engineering, build whatever you want that will win and we will pass it through tech. So at Pomona in 1972, there were 39 cars that came to race Pro Stock with real bodies in white, and Jenkins with his tube frame job.” Making the new ’72 Motown Missile ‘Cuda, recently featured on the cover of Hot Rod Magazine, obsolete before it ever turned a wheel. “That’s when I sent Coddington to Ron Butler’s shop to oversee construction of our ’73 A-body”.

But NHRA was determined to strangle the Chrysler program by requiring their cars to carry increasingly disproportionate amounts of weight. Innocently called “factors,” they were systematically administered to ensure the Chrysler cars could never be successful again.

Dick Maxwell explains, “We worked very hard to learn and gain a technological edge but had to dole it out very cautiously, so as to not get factored worse. But our guys were trying to make a living. And if we had something going, we wanted to give it to them so they didn’t lose too bad, while trying to manage the risk of getting our cars factored even more.”

Before the ‘74 season Maxwell, now head of Chrysler’s Race Program flew to LA to meet with NHRA officials. “I asked them, if we can get our cars competitive with the current weight breaks are you guys going to stack even more weight on us? They leaned back and said ‘you bet’.” Tom Hoover now reveals, “Recently, at the 50th anniversary of the Hemi, Wally Parks apologized for having done what they did to us. He said it was a mistake. It was nice to hear but I must say I was astounded to hear him admit it.”

So the hour was late and time marched on with its opportunities in tow. By Labor Day 1974, the Ramchargers were able to accept the fact that their mission was over.

Tom Hoover reminisces, “I remember it well, walking out the gate of Indianapolis Raceway Park with Maxwell and Coddington for the last time. That was the day we all knew the war was over and it would be a waste of the company’s money to continue. Regardless of what we did, NHRA was going to factor us out of competition. That’s the end. There isn’t anything else you can do. They just kept adding weight until the other guys win and you’re screwed. That’s it. That was doomsday. They had been successful. The Ford engine in the little Pinto and Jenkins and his whatever Vega. There was just no way.”