Chrysler’s Stock Car Connection –Part 11

GEARING UP FOR ‘67: Nichels expands his operation as Chrysler designates him as the sole source for Stock Car hardware.

By Wm. R. LaDow Photos from “Conversations with a Winner—The Ray Nichels Story.”

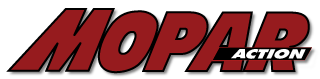

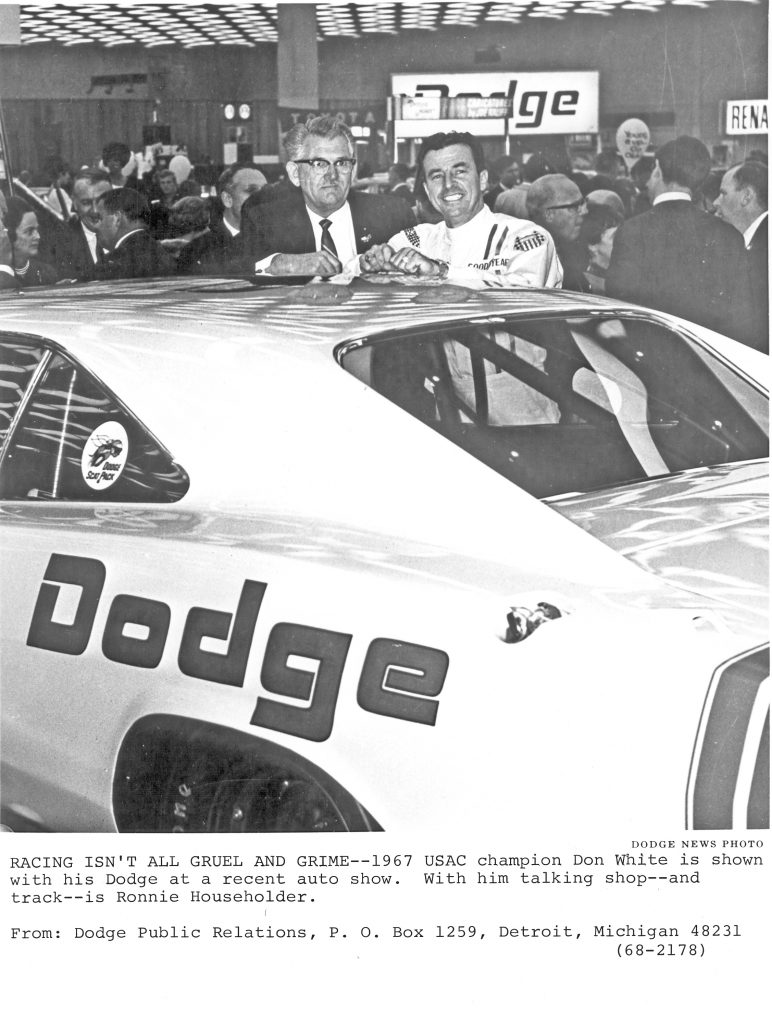

Chrysler touted their successes on the track to promote the sale of Dodges for 1967.

The words written on the chalkboard were wide and tall, with the writer using the chalk on its side rather than the tip … written in three inch wide letters were two simple words, “WORK TONIGHT.”

Due to a series of clandestine decisions by Ronney Householder and the Chrysler corporate brass there was “WORK TONIGHT” almost every night at Nichels Engineering’s “Go-Fast Factory.” While Householder and other Chrysler executives like Frank Wylie were telling anyone who would listen during the summer and fall of 1966 that they were reducing their corporate involvement in stock car racing, the reality was, they were about to ratchet up their commitment considerably. Though funding for racing projects was becoming a bigger and bigger problem at Chrysler, Householder and colleagues were forging ahead. Meanwhile, Ford’s ever increasing commitment to motorsports now included a substantial presence in Indy car and International Grand Prix racing and the American automotive juggernaut was spending money on racing projects like there was no tomorrow. In the case of Chrysler, Householder had to find ways to be more resourceful and efficient in his approach. Company executive Lynn Townsend had led the Mopar brand back into racing in the early 1960s and it was obvious that his efforts resulted in increased market share among the big three American automakers — General Motors, Ford and Chrysler. It was no coincidence that on January 1, 1967, Townsend was named Chairman of the Board of Chrysler Corporation. There was no turning back from marketplace now. The challenge was clear, go faster on America’s race tracks and sell more cars to the public.

One stop shopping

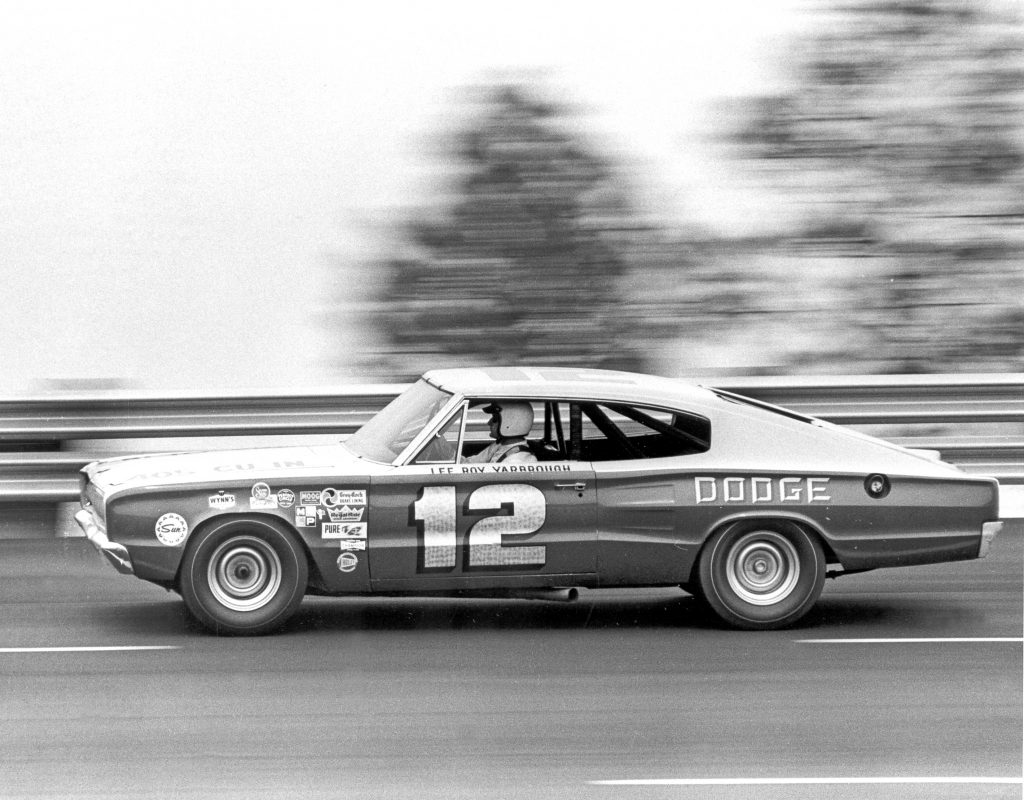

The first announcement by Chrysler Racing Chief Householder was a stunner. Effective immediately 100 percent of Chrysler’s entries for the upcoming stock car racing season, both Plymouth and Dodge, were to be constructed at one location, Nichels Engineering. Sole source supply of chassis, engines and parts support would come directly from the “Go-Fast Factory” on East Main Street in Griffith, Indiana. Cotton Owens, Norm Nelson, and Petty Enterprises were all being directed to obtain their cars from Nichels Engineering rather than spending the few precious weeks between the end of the 1966 season and the start of 1967 season building their own equipment. Once again all Chrysler race teams were told that they were more than welcome to contribute mechanics and drivers to the off-season car construction effort at Nichels’ operation and Ray would gladly put their people on the Nichels Engineering payroll.

Nichels’ race car construction business increased so dramatically that the 40,000 square foot operation quickly ran out of floor space and the staff began suspending car bodies from the rafters of the main bay of the Main Street complex. The superbly skilled car builders and mechanics of Nichels Engineering were now working more hours per week than ever. Many an area child, participating in local after-school activities such as sports or concerts, knew that it was unlikely that they would perform in front of their own fathers, because of the relentless production demands of Nichels’ off season car construction schedules. Such was life in the industrial heartland of America, known as the Calumet Region.

Business is booming

The upcoming season offered not only increased racecar production demands but other challenges as well. Nichels’ other businesses were growing rapidly. The Griffith Airport and its key tenant, G&N Aircraft, were busier than ever, requiring more employees and more space. Nichels then formed another partnership with Paul Goldsmith and opened a series of automotive operations known as the Nichels & Goldsmith Safety Centers. Their first operation was at the Cline Avenue shop in Highland, where Ray had gotten his start. He put the business under the capable management of his life-long friend George Marren. The Nichels & Goldsmith Safety Centers performed engine rebuilding and balancing, tune-ups, complete brake service, front end alignments, installed Thermo-King air conditioning units and sold Goodyear tires. In addition to those services, the Safety Centers also catered to those who sought Nichels-like speed, by offering equipment, parts and service for the street, strip or track. In a matter of no time, the growth of this business escalated substantially with operations opening in Hammond, St. John and South Bend, Indiana. Last but not least, Nichels quietly made a move south, by opening a Nichels & Goldsmith Safety Center in Charlotte, North Carolina. The shop in Charlotte started in a temporary location not far from Charlotte Motor Speedway. Ray was convinced that he needed a presence in the Charlotte area to support his (and Chrysler’s) race teams from a southern location. Although it opened as a commercial automotive entity, Ray had much bigger plans in store for his southern venture. This operation gave Nichels Engineering much needed storage and operational facilities in what Ray considered the center of southern stock car racing. In the not too distant future, Nichels would unveil his plans for the substantial growth of the Charlotte operation.

Team effort

As the 1967 racing season moved closer, the Chrysler racing contingent underwent some changes in its makeup for the upcoming season. In the case of Nichels Engineering, Ray decided to go with a two-car team. Paul Goldsmith, now 39 years old, would pilot a brand new 1967 Plymouth GTX in NASCAR, running a limited schedule of 21 races, just as he had done in 1966. The rest of Paul’s efforts would revolve around racecar engineering, research and development.

Meanwhile, 40 year-old Don White would be behind the wheel of a new 1967 Nichels’ Dodge Charger in his quest for a second USAC National Stock Car Championship. Nichels would also enter White in several NASCAR speedway and superspeedway contests through his FIA license. As the Nichels operation ramped-up production, Chrysler Corporation again made clear the task at hand for Ray Nichels and his company. Nichels Engineering would run cars for the primary purpose of analyzing performance and safety engineering. If the Nichels’ cars proved victorious, that was fine, but the principal focus remained to be the further pursuit of automotive research and development of Chrysler engines, chassis and secondary automotive supplier’s parts. Nichels clearly understood his assigned task and the relationship in developing components that defied failure, which in the long run made America’s highways safer. It was one of the primary goals outlined by Ray Nichels when he founded Nichels Engineering in 1955.

Although touting its reduction in support of Chrysler race teams, the upcoming season offered a familiar list of names running the Mopar brand. Chrysler teams in NASCAR would again be Cotton Owens, Ray Fox, Petty Enterprises, Jon Thorne, Tom Friedkin, James Hylton and Nord Krauskopf’s K&K Insurance team. In USAC, Norm Nelson, Sal Tovella, Butch Hartman, Rudy Hoerr and Dave Whitcomb, to name just a few, would again field race teams using Chrysler (and Nichels Engineering) as their primary supplier.

In NASCAR, the overall schedule was again daunting. For a driver to chase the season championship, he had to be willing to race from the season opener at Augusta, Georgia on November 13, 1966, right through the season finale at Weaverville, North Carolina on November 5, 1967. The NASCAR schedule consisted of 49 races, with 14 races contested on dirt tracks, 34 races on paved tracks (13 of those being run on superspeedways) and finally a single race scheduled on a road course.

The USAC schedule offered its own challenges with a total of 22 races, utilizing a unique balance of road courses, dirt ovals and paved speedways. The season opener was on the road course at Indianapolis Raceway Park on May 27th, with the season finishing up at Milwaukee on September 17th. Once again the Milwaukee Mile was the anchor of the USAC stock car schedule with four contests scheduled on the world class paved oval, ranging from 150 miles to 250 miles in length.

Level playing field

Back at the “Go-Fast Factory,” the lights burned deep thru the winter night, as drivers and mechanics from race teams across the United States gathered to work alongside Nichels Engineering’s staff to build the 1967 fleet of Dodge and Plymouth racecars. When mid-January rolled around, a drawing was held to select which completed cars accompanied the mechanics and drivers back home to their respective racing operations. Early in the process Ray Nichels and Jim Delaney had made it clear that no mechanic would be allowed to focus his efforts on just one or two cars. Doing so, might allow for an individual or race team to gain an unfair engineering advantage before the car left Nichels’ jurisdiction. Ray had made it clear, in fact, demanded, that all of the Nichels Engineering cars were to leave the “Go-Fast Factory” as equally prepared in performance characteristics as possible. Once the individual race teams got their rides back to Level Cross, North Carolina (Petty Enterprises), Spartanburg, South Carolina (Cotton Owens) or Racine, Wisconsin (Norm Nelson Automotive), the individual teams could work their own magic on their respective cars. In Ray’s judgment, it was the ethical and honorable thing to do.

Nichels’ autonomy from the center of corporate automotive power in Detroit and the racing communities in the southeast allowed him to take such an approach. Ray had a responsibility far beyond merely supplying cars to various teams. Nichels-built cars, without exception, had to be above reproach when inspected at the various tracks by the sanctioning bodies. If a Nichels car was found to be blatantly out of compliance, it might create windfall of disqualifications by the NASCAR or USAC inspectors, impacting all of the Chrysler teams. Uniformity was the rule, not the exception.

Rule ballet

Nichels had made it a point to work hard at satisfying NASCAR and USAC inspectors at every juncture. NASCAR had been the most challenging due to the ongoing debate about what was, or wasn’t “stock.” The implementation of body templates made things even more challenging during the course of the recent season. Ray made it a point to know the inspectors and the inspection process. Over time Nichels had developed a solid relationship, based on mutual respect, with NASCAR Chief Inspector Norris Friel. Nichels had known Friel from his days with the American Automobile Association (AAA) before they had stopped sanctioning racing events in 1955. For the past ten years, Friel had been the key player at NASCAR. During that time, Nichels and Friel had worked together to insure that whether it was a Nichels’ Pontiac or Nichels’ Mopar, it was clearly within race specification. Neither Nichels nor Friel had any interest in having a triumphant car’s legality questioned after making it to the winners circle.

In fact, on several occasions, Nichels and Friel had performed a bit of a ballet during the inspection process. Nichels always made it a point to leave the inspection duties to his crew chiefs during race weekend. But almost without exception, Ray would hear his name bellowed over the track public address system ordering him to report to the NASCAR Inspection area. Once there, Norris would begin lecturing Ray about a series of out-of-compliance conditions found on one of Nichels’ cars. Ray would then politely ask Norris if there was an office nearby where they could sit down and review the NASCAR inspection report more closely. Once Ray got a good look at the data, he would feign surprise and break out in an angry tirade, promising to fire his crew chief and mechanics immediately, as he appeared to storm out the door. Friel would quickly calm Nichels down, telling Ray that there was no reason for anyone to lose his job over the issue, just as long as the rule discrepancies were corrected and the car re-inspected. Ray would look Friel in the eye and faithfully promise to get the cars into compliance. Ray then headed off to the garage area, where he would raise hell with his own crew chief, not for being out of compliance, but for getting caught by the inspectors and putting the other Chrysler race teams in jeopardy by causing them to undergo more detailed inspections. Lastly, Nichels knew if he could draw the attention of the inspectors away from the other Chrysler team cars, for any amount of time, it could help their competitiveness when attempting to match up with master rule benders like Junior Johnson or the Wood Brothers.

When Nichels first dealt with Friel, he was surprised to learn what a stern taskmaster Norris was. But in time, Ray learned that Friel maintained a forceful facade to keep those with thoughts of abusing the inspection process at bay. Ray slowly began to realize that if you showed respect to Norris Friel, you in turn would come to be respected. Those who worked hard at being respected by Norris Friel soon gained his friendship too. But sadly, before the new year had even started, the relationship that Ray had worked so hard to cultivate over the past decade was gone in an instant when Nichels learned that his good friend, the 60 year-old Friel had unexpectedly passed away on November 26, 1966 following surgery. It was a shock to the entire NASCAR community. Norris Friel, who had the toughest job in stock car racing, was also one of its most respected men.

Setting more records

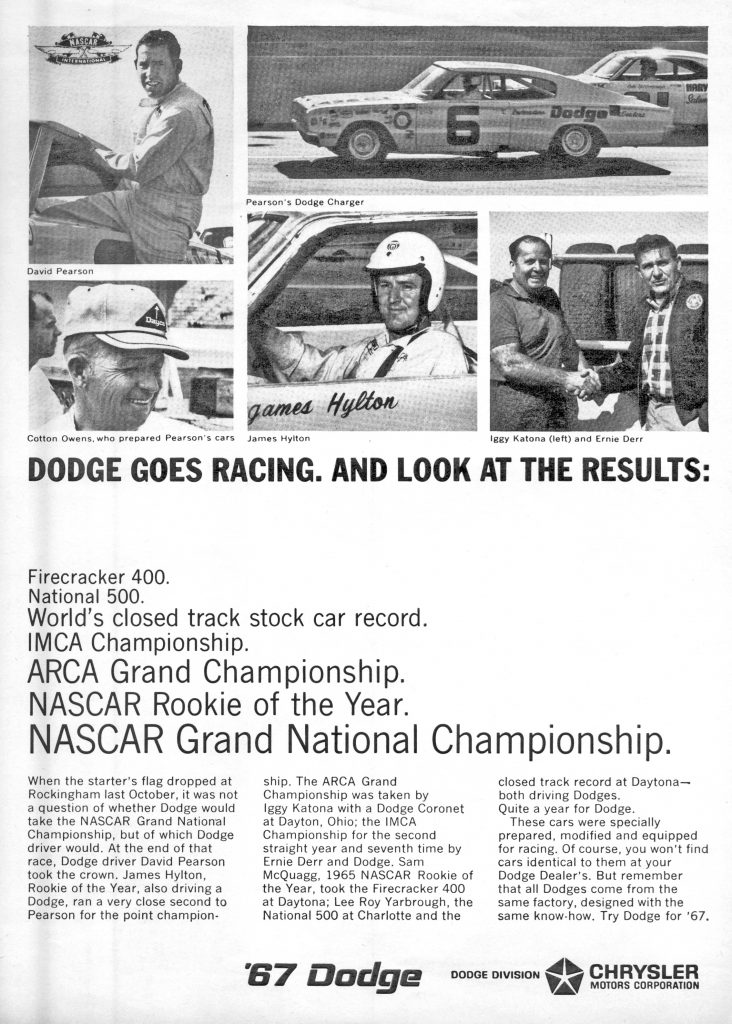

The stock car racing landscape was already volatile even before the passing of Friel. During the off-season, NASCAR was already voicing its concern about the technological advancements in the engines, chassis and tires being made by the Chrysler teams. There was little more evidence needed that Chrysler Racing was indeed “bringing it,” when on Thursday, November 17, 1966, at Daytona, LeeRoy Yarbrough in his Nichels-built Jon Thorne Dodge Charger, electrified onlookers by snapping off a lap at 183.112 mph, a new closed course worlds record. Yarbrough running Firestone tire tests ran 40 laps on the two and half mile superspeedway with only eight of those being below 180 miles per hour, proving that his world speed record was by no means an aberration. When the Firestone tests were completed a week later, Yarbrough had run 1,040 miles for an average speed of 179.121!

Weather pain

As the staff at Nichels Engineering worked their relentless racecar production schedule in January, even the weather seemed to be on overload. On January 16th, the temperature in the Calumet Region hovered around zero degrees Fahrenheit. The two Nichels race teams heading out to Riverside for the Motor Trend 500 were thrilled to get away from the cold “Hawk” winds and on their way to southern California.

But by Sunday, January 22nd, as the NASCAR race was being started in the rain at Riverside, the temperature in Griffith had risen to a very unseasonable 60 degrees. There was neither rhyme nor reason for it, in fact to most Hoosiers it just seemed like another dose of chaotic Indiana weather. But four days later, the weather at the Main Street “Go-Fast Factory” took a turn for the worse. On the morning of Thursday, January 26, at just after 5 AM, it started to snow. It snowed through the morning into the early afternoon. Coupled with strong frigid winds, the snow continued to pile up and block everything in its path. By mid-afternoon, transportation was coming to a standstill. People began to come to the realization that the storm wasn’t going to let up and started to leave their places of work early, many to be stranded and never making it to their own homes. Schools concluded their classes in the early afternoon fearing that they wouldn’t be able to get their students home safely.

By late afternoon, stories of people stranded all through the Calumet Region and greater Chicagoland area were being repeated over and over on Chicago radio stations WGN, WLS, WCFL and local station WJOB. As the daylight began to vanish at the end of late afternoon, many region industries such as the steel mills, refineries and foundries were begging their employees to stay on-site. Plant managers fearful that the employees on the upcoming shifts wouldn’t be able get into work, worried that without enough staff, their factories would subsequently experience equipment shutdowns that would damage their facilities for several months. If you were in the business of casting iron, making steel, forming glass or refining oil, you were looking at the potential of catastrophic losses measured in the millions of dollars. In the meantime, it just kept snowing. Wherever you were, you stayed. Food and medicine became precious commodities. Fatalities began to mount, as some 60 deaths were attributed to the record-breaking storm, many tied to heart attacks from shoveling snow.

Midmorning on Friday, the falling snow mercifully started to subside after depositing 23 inches in and around the Chicagoland area. The Hawk winds off of Lake Michigan piled the snow into huge drifts, six to ten feet high. Transportation came to a halt. The Department of Streets and Sanitation in Chicago, estimated that 75 million tons of snow covered the Windy City, and it was believed that an equal amount coated the Calumet Region. For the next 10 days, wind, cold temperatures and more snow battered the area. Schools and businesses were force to close for several days. The region was virtually paralyzed. Many simply surrendered to Mother Nature and waited it out. But not so for the employees of Nichels Engineering. The “Go-Fast Factory” didn’t have that luxury. Daytona Speed Weeks was only a few weeks away. Racecars, Hemi engines and parts had to be finished and readied for the trip south. Failure was not an option.