Chrysler’s MOTOWN MISSILE- Part 1

Mopar’s Secret Engineering Program at the Dawn of Pro Stock 1972.

Story and photos by Geoff Stunkard

COVID19 – Due to

unforeseen delays in manufacturing and shipping time, this volume now has a

scheduled release date of 7/1/2020.

This excerpt is unabridged from “Zookeeper” Geoff Stunkardâs upcoming

book by CarTech: âChryslerâs Motown Missile: Moparâs Secret Engineering Program

in the Dawn of Pro Stock,â and covers 1972. While earlier chapters recount

Chryslerâs racing program through 1971, this section focuses on the teamâs new

âCuda and the conflicts up to the 1972 Winternationals. This is the first of 3 parts,

which will be published online as the series for this transitional year

continues. Select photo can be found in the June 2020 issue of Mopar Action

magazine, on sale in mid-April at better retailers or at moparaction.com.

THE 1972 BEGAN IN 1971, SEEN HERE WITH THE EARLY GRILLE FITTED INTO THE NOSE.

The dramatic election year of 1972 was an appropriate backdrop of what was going on with the Motown Missile program and Performance Automotive during this season. The cultural changes begun in the 1960s had begun to emerge in earnest, and the nationâs biggest political battle pitted law-and-order President Richard M. Nixon as the âtraditionalistâ against the more liberal policies being promoted by followers of former bomber pilot turned flower-power-champion Senator George McGovern. Top 100 hit music ranged from crooners like Don McLeanâs âAmerica Pieâ to the thunderous metal of Argentâs âHold Your Head Upâ and Alice Cooper proclaiming, âSchoolâs Out ForâŠEVER!â Drama seemed to be part of the moment.

By the yearâs dawn, the era of the American supercar had passed, though there was still a very strong interest in automotive performance by the public. For its part, Chrysler continued to offer a line of full-size cars and sporty mid-size models, utilizing imported Crickets and Colts from Japanese manufacturer Mitsubishi to meet the growing demand for so-called minicars. Of the Big Three, the Chrysler Corporation had always made do with less. After Dodge and Plymouth again won NASCAR, USAC, IMCA, ARCA, and NASCAR West championships in 1971, the company announced they were done with circle track racing research projects as a corporation amid tightening budgets. The development role would now be assumed fully by Petty Enterprises. Indeed, all of motorsports was in a state of flux as a result of Detroitâs teutonic shifts away from muscle, and among the rules for NHRA Pro Stock as 1971 wound down would be a banning of all Hemi-type engines as non-production powerplants by January 1st, 1973, with a more radical rumor of nothing over the 366â 6-liter margin being part of this.

Nonetheless, Pro Stock in all the drag race sanctioning bodies continued in its popularity and many changes would be part of the 1972 season. For Ted and his crew, as well as the engineering guys at Chrysler, it would be both a change in focus and a change in racecars.

Performance Automotive to SVI

While testing efforts with both the Motown Missile and the sportsman drag packages would continue as part of his work, Tedâs business model had morphed from being simply race and performance car oriented into one that would be doing specific vehicle projects that Chrysler wanted done. The result was a name change to Specialized Vehicle Incorporated during this year, and by the end of 1972, driver Don Carlton would become the actual owner of the Missile racing business.

âAnother thing played into how much we could do here at our shop after â72,â Ted now remembers. âYou know, by the end of that year, they (Chrysler) wanted me to do a lot more stuff; it was not just Pro Stock any more. There was a push to be sure that the bean-counters did not cancel us out. You know âwhy are we paying this guy; we could be doing this stuff in-house with the union guys.â Bob Cahill wanted to justify our existence, so we did projects. The parts for the featherlight Duster, we did that, and we did development on the âLil Red Express truck. So as my duties changed, that was the biggest reason Donnie took the drag car program over. He got the car deal and I stayed on board under SVI to do engines for him.â

He continues. âAt that point, SVI was actually getting bigger because we were doing more. The engine deal was now a part of that whole thing. We were still doing the sportsman stuff. I hired a guy, Ross Smith, who was like Jimmy Addison, a very bright young guy. So I gave him a list of what we would be testing, and he would get things ready and get whatever car to the track. I was busy with other stuff by then. Eventually he ended up at GM in Advanced Engine Development; he was very smart.â

Of course, this would happen later. Ted would own the then-under-construction Motown Missile Plymouth âCuda for the 1972 season, and Donnie continued on as the driver working for him. This new car would garner more publicity then any priority iteration by the team. Since he wanted to continue in the racing program, Dick Oldfield would go to work directly for Carlton until 1977, when Ted hired him back.

The Motown âCuda

Of course, Mr. Hoover continued to be the defacto champion of the Missile cause, and with basically 18 months of flogging the Challenger, many things had been learned. That in turn meant a new car was going to be needed soon enough. The sport had evolved during the two racing seasons, and while the original Missileâs testing schedule was still very aggressive, it fell on Tom Coddington under Hooverâs direction to execute applying some of that fresh knowledge to a new vehicle, which had already been chosen as a Plymouth Barracuda.

âWell, we had used the â71 car for two years, including all the test runs on it, and you could watch it do the watusi as went down the track,â Ted laughs. âIt was time for a change. It was worn out for testing, too, as you could see the whole car shift when you let the clutch out.

âThe factory told us if we did build a new car, it would need to be a Plymouth because we had just run two years as a Dodge and it was a Chrysler promotional program. The biggest change from a construction standpoint would be a better chassis, a better rollbar design, and we went to the leaf link rear suspension. Pete Knapp, Dan Knappâs younger brother, came in to work for me and he was a good welder. We got another body-in-white but we did not need a street car this to time to convert the car.â

NHRA had been reworking the rules during this period as well. Editor Jim McCraw of Super Stock magazine opined that there likely not a single âlegalâ car in the sport based on some of the current rules. The racers had always been creative in their interpretation, and the next Missile would be as trick as anything else out, at least during the era of its construction.

âAll the titanium stuff we had figured out with the Challenger was part of that build,â Ted notes. âIt had been an evolutionary process to get there. For instance, we went with some titanium bolts, but we found out they could not constantly be taken in and out; they are just not as strong. We learned you would sometime need to sacrifice weight for durability, especially after you have broken a few bolts off. You say, âwell, this isnât going to work! It didnât save time or money!ââ He adds wryly, âThen it was useless, because they changed the rules and you had to put that 400 pounds back into it anyhow!â

The earliest images of the car under construction date to April of 1971, showing it with a â71 Cuda grille in it. There had been already been some magazine reporting that the team was getting a second car ready, but as noted from the race and testing schedule in the last chapter, time in a day could only go so far.

âWe started building that car in the late summer of â71, August or so,â Ted recalls now. âI donât think they had announced the weight changes yet. The car was done by December. We knew we would not be going back to the automatic, so it was set up as a manual car from the start. It had the rear suspension changes done and we added a dry sump as well.â

âThe car would still be used for testing but there was not a lot of extra stuff we did for that; it was still pretty spacious in the engine compartment and we may have made the inner fenders easier to remove. We did make the tunnel bigger so we could access the bellhousing and transmission quicker for in-between rounds changes. There was no removeable front end and the doors did not come off easily yet, like they do now.â

Nonetheless, there was quite a bit of re-engineering. In the front suspension, engineering understandings made a switch to a Cam Gear rack-and-pinion layout similar to what was being employed by the new Ford Pintos. By fabricating various parts out lighter materials, the new result freed up a considerable amount of weight, as did the removal of 20 pounds related to the OE steering layout. Inverting the steering arms from side-to-side with accompanying changes to the A-arms also allowed the car to maintain positive caster under acceleration, improving stability at speed.

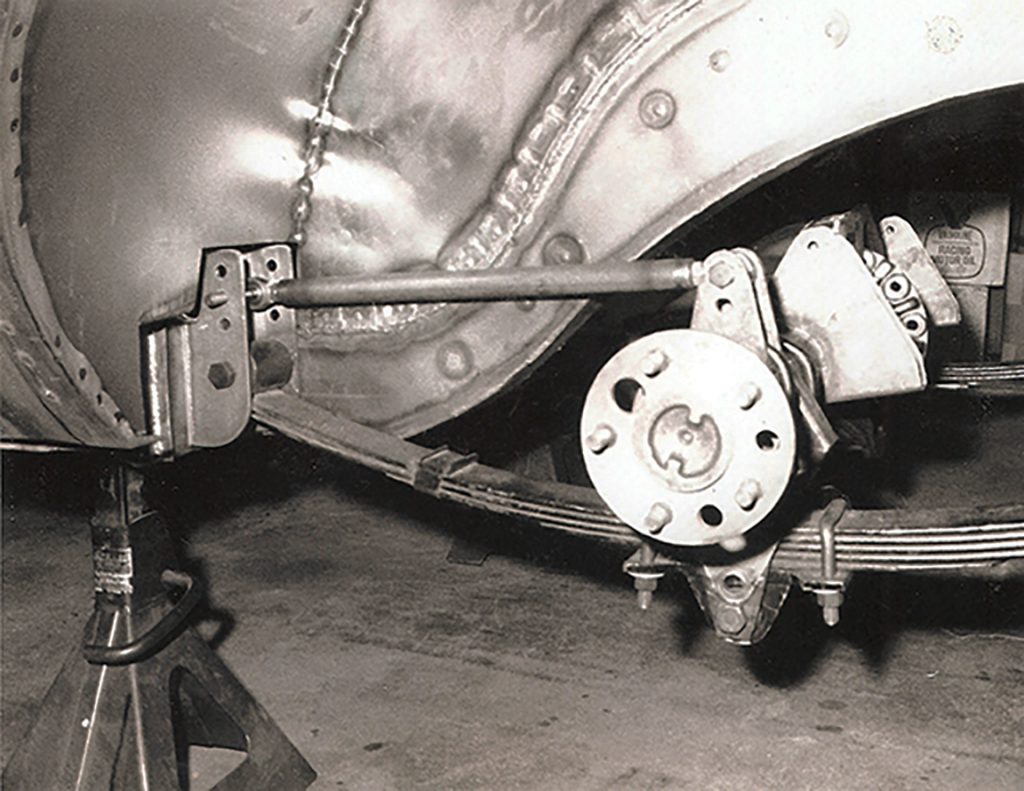

NEW SUSPENSION DEVELOPMENTS WERE CONTINUING IN PRO STOCK. THIS IS THE LEAF-LINK DESIGN.

The rear suspension was a leaf-link design that offered substantial improvements from the prior car in adjustability as well. The leaf-link used a conventional bias-design Chrysler Super Stock leaf spring set, moved inbound onto the factory frame rails. At its front, a round bar ran directly above that half of the spring from the narrowed Dana rear housing to a multipoint vertical mounting bracket, which was added to the car at the rollcageâs lower crossmember; that position held the front of the spring as well. This could allow either the bar or the spring to be adjusted for track conditions and desired height without changing the pinion angle. Even with the car kept with its proven standard 2-degree rake, the team had a lot of possible adaptations here. The rear of the spring was held in a static position. Also, the frame longitudinals remained in the stock location, with wider wheeltubs for tire clearance. Working with a custom roll cage designed by Coddington that made use of multiple triangulations to increase rigidity, this package was a big step forward.

Of course, the new dry sump was a crucial part of this working, as it allowed a significantly lower nose stance over a conventional wet-sump pan beyond the more obvious benefits of oil evacuation away from the crank. The tank for the dry sump was located in the front of the engine, off to the passenger side. The car was equipped with front disc, rear drums, and two Line-Locs, one to hold the front wheels for the burnout, the second to hold the rear firmly on the starting line.

The car began as an acid-dipped body-in-white, with fiberglass components where the rules allowed. After its construction, the choice was again for black paint, this time augmented with gold leaf lettering, painted by the same people who had done the Challenger. Ted also garnered a nice sponsorship program from Lee Filters as the car went together. âI hated having a lot of decals on the car,â Ted admits. âLee was a bunch of companies – Lee filters, Cyclone headers, Fenton wheels, Eelco linkages. Then we had Liberty (transmissions) and Trick Titanium, which was Apollo Weldingâs growing business in race car parts.â

EARLY TESTING IN LATE 1971 IN FLORIDA. SPONSORSHIP DECALS WERE CAREFULLY PLACED TO PREVENT THE “CLOWN CAR” LOOK.

With the âCuda just completed at the end of 1971, HOT ROD magazine did a major photo shoot on it that resulted in the cover story of that magazine in their January 1972 issue. One of photographer Bob DâOlivoâs images showed all the team members depicted in various positions of responsibility, spare parts positioned all around. Meanwhile, writer John Dianna gave an excellent 7-page analysis of the carâs construction, using DâOviloâs work and images taken during construction. Testing started in earnest in Florida in December, and the Missile crew did not attend any of the sportâs early season events leading up to the first weekend of February, when NHRA would host its season-opening Winternationals in Pomona, California.

THE HOT ROD MAGAZINE COVER ENDED UP ON THE BACKING BOARD FOR A DIECAST TOY “MOTOWN MISSILE” OVER 40 YEARS AFTER THE CAR WAS RACED!

Before Pomona â The Shape of Things to Come

We noted that the American minicar had arrived, in the form of Chevroletâs sporty Vega, the Ford Pinto and AMCâs little Gremlin. NHRA had heard an earful from anybody not named Sox about how boring the class seemed to be. While not exactly true, what was fairly usual was at least one Chrysler A- or E-body of some sort in every final round, and Sox won most of those. Indeed, Plymouth had won every NHRA Pro Stock event title for two years other than one by Landy (Dodge), one by Nicholson (Ford), two by Jenkins (Chevy) and the World Championship pass of Mike Fons (Dodge). With Detroit no longer offering big inch performance motors in thier models, NHRA was also concerned about the classâs future relevance.

William Tyler Jenkins of Malvern, Pa. was never anybodyâs fool. While short in physical stature, his Mensa-level mindset was always working something out. His nickname âGrumpyâ even allowed for his temperament, which could be terse, pointed and often noted in print ending in the term, âhrmph!â Jenkins had been shut out of NHRAâs final rounds since his two wins in early 1970. It is still not known how much influence he had been able to put on the powers-that-be, but the result was the first of NHRAâs true tube-frame Pro Stock cars, which emerged from his shop for the 1972 season.

The Vega was Chevroletâs âCar for the Seventies,â sporty but economical. Jenkins, who had a backdoor research-and-development from the company that was never admitted to but well-known, took all of his lengthy knowledge of the small-block Chevrolet to create a 331â engine that would allow the car to weigh a mere 2,234 pounds. That was because NHRA had adopted new sliding weight ratios, with inline wedge valvetrain designs like the Chevy set at 6.75 pounds per inch. Other groups were at 7.0 for canted valve designs like the Chevrolet big-block and Ford Cleveland, and then an increase to 7.25 for Hemi-style big-blocks or other designs. This meant that the Cuda, with its 426 + .020-CI had to now weigh 3098, almost 900 pounds more.

âI give Jenkins credit, because those guys did a good job,â says Ted. âBut when we got to Pomona and saw it, the handwriting was on the wall. There was not much more we could have done to our car to change it by then. We stayed about a month on the west coast and tested; we only ran the NHRA race, and I donât remember if we even did any real testing before the Winternationals. Remember, we did not do a lot of match racing with the Motown car.

âI guess, thinking about it now, the shock really came after that first race. It was first, âwow, did we take a wrong turn,â followed by, âwhy werenât we allowed to do this stuff.â Why werenât we, meaning Chrysler Corporation, and to the same extent, Ford, in on making this decision. Why did GM get to do this stuff? We had just built this car, spent all this time and money, and itâs already obsolete. It could still win a race; we won at Gainesville the next month, but the writing was on the wall.â

In Jenkins defense, he had followed the letter of the law. The tubular frame retained the semblance of the âstepped frame accepted/stock frame retained,â though little remained of what came from the stamping plant. The real benefit was two-fold â the small high-winding displacement coupled to the weight, and the use of the semi-adjustable coil-over shock absorbers. NHRA had allowed for a somewhat unsafe 2000-pound minimum that year for all 94-99.9 inch wheelbase minicars; 2400 was the minimum of any American-built vehicle with a wheelbase of 100 inches or more. Incidentally, the Colt and Cricket were both under 94 inches in wheelbase, rendering them illegal for NHRA Pro Stock from the start.

Winternationals of Discontent

When the tour rolled into Pomona in early February, the rules was settled for the moment and it was time to go racing. Super Stock magazineâs logically coverage broke it down as Group 1 (7.25 maxi-cars), Group 2 (7.0 wedge cars) and Group 3 (6.75 mini-cars). The field was still led by Mopars, McDade in Steppâs car at a 9.59, then Leal, Sox, and Grotheer. Next was Dyno Donâs Maverick, then Landy, then the new Missile, but basically all the top 16 cars were Group 1 Hemi Mopars or SOHC/Boss Fords. In 17th was Bill Jenkins and his just-built Group 3 Vega, powered by its 331-CI Chevrolet small block with an ill-handling 9.90, and the final car in the field of 32 was clocked at 10.74, creating a program of 20 Mopars, six Fords and six Chevrolets.

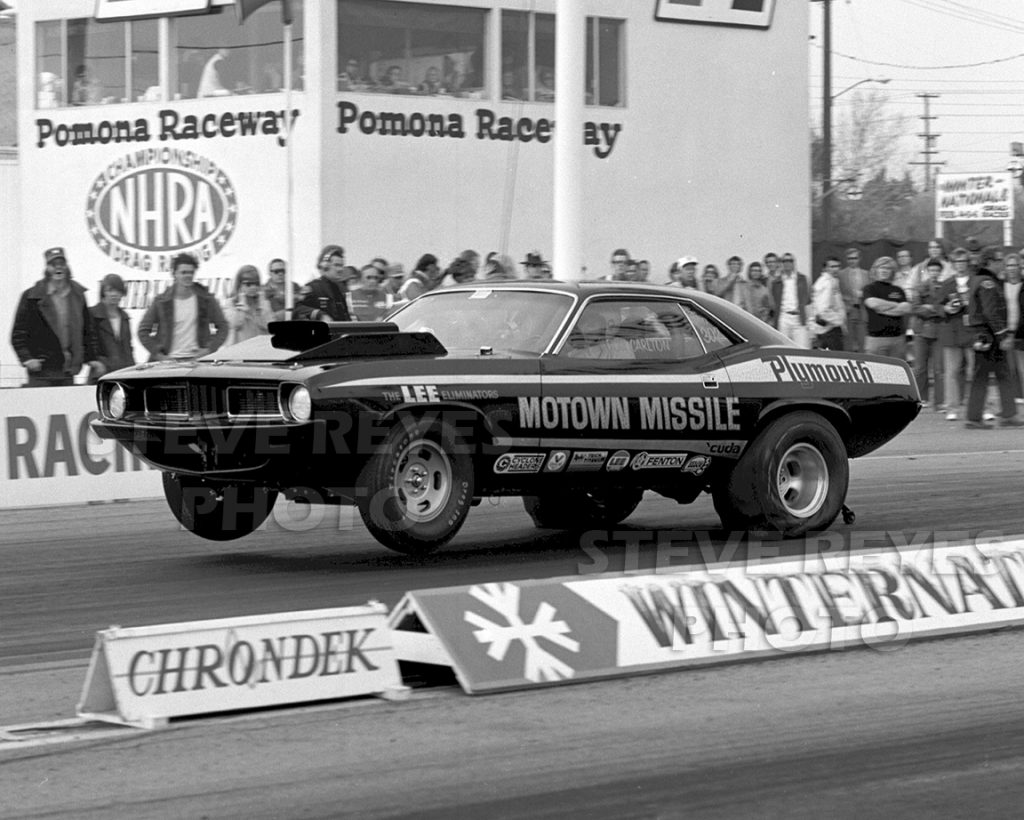

LEGENDARY RACING PHOTOGRAPHER STEVE REYES WAS ON THE SCENE AS DON CARLTON DEBUTED THE NEWEST MOTOWN MISSILE. ALAS, THE DAY ENDED AGAINST A RESURGENT BILL JENKINS AND HIS “WHAT? THAT’S LEGAL?!?” VEGA.

Though the Vega passed tech, there were immediately a number of competitors who asked questions regarding its letter-of-the-law eligibility. At that, the NHRA Tech people from Jack Hart down basically shrugged these concerns off; the newest and smallest-ever Grumpyâs Toy was going to run on Sunday no matter what.

Since the qualifying result put Jenkins against McDade in the first round (#1 vs #17), the Vega was figured to be a novelty, but after some suspension tuning Jenkins was âsuddenlyâ fast, hitting a big 9.63 to trailer the Billy the Kid entryâs 9.74. Next came a quicker 9.62 over Bill Bagshawâs Challenger, a 9.73 over Melvin Yowâs Dodge, and a semifinal meeting with the Missile. Carlton had been consistent all day, beating the S&M-built Ronnie Lyles âcuda with Joe Fisher driving in round one, a 9.78 win over Fast Eddie Schartmanâs Ford in round two, and a wonderfully-scripted holeshot victory over Sox himself, 9.68 to a faster 9.64, to get a chance to stump the Grump. Prior to the semifinals, Jenkins reportedly thought his engine was badly damaged and was said almost ready to forfeit the event when his crew discovered it was a simple valvetrain problem. Then NHRA gave him time to repair it, and at the green against the Missile, the Chevy headed to a 9.70. Carlton rowed through the gears, but a head gasket gave way. He slowed to a 9.84 to watch the Vega get its first win of â72. In the final, Jenkins was racing multi-time event finalist Don Grotheerâs Plymouth, and the âmouse that roaredâ won handily, 9.68 to 9.82. It was indeed a new era.