Running the Pikes Peak hill climb in a vintage Mopar.

By Bill Woods Photos by Jess Neal

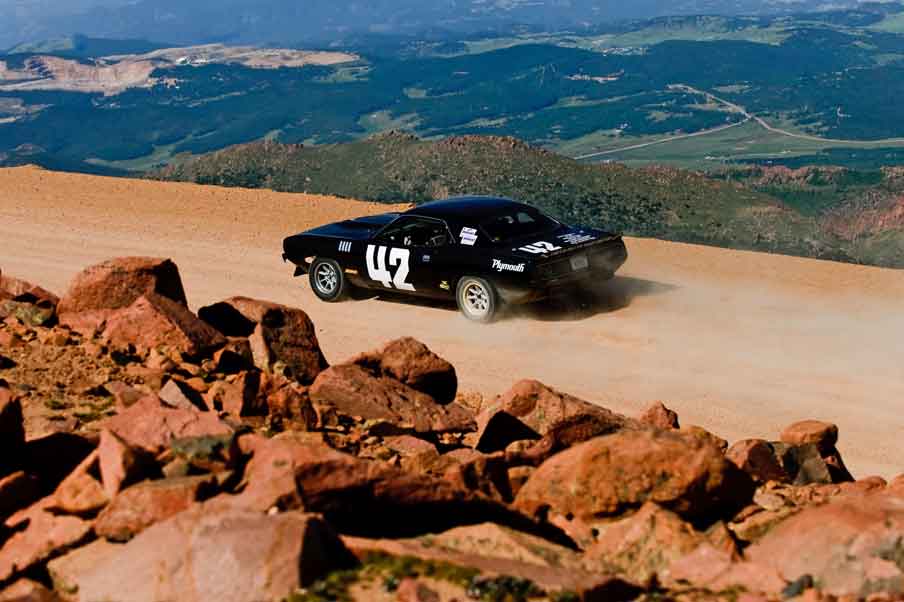

Jess Neal dirt-tracks around a posted 10 MPH corner. There’s no much out there beyond those rocks. (Photo: Artemis Images)

3 a.m. Most people are asleep, getting up to go to the bathroom, or watching fitness machine infomercials on TV. At 3 a.m. Jess Neal is unloading his ’71 ‘Cuda off his trailer. It’s dark. He’s parked in the trees and it’s his 50th birthday.

Jess has spent the last three days in mandatory practice for a race—an unusual venue for a vintage Mopar. It’s a hill climb on a 12.42-mile mile course in Colorado Springs, CO, that throws both dirt and tarmac sections at the racers. The course rises from a starting line elevation of 9,390 and climbs another 4,721 feet to the 14,110-ft. summit. To get there requires navigating 156 turns that include tight switchbacks.

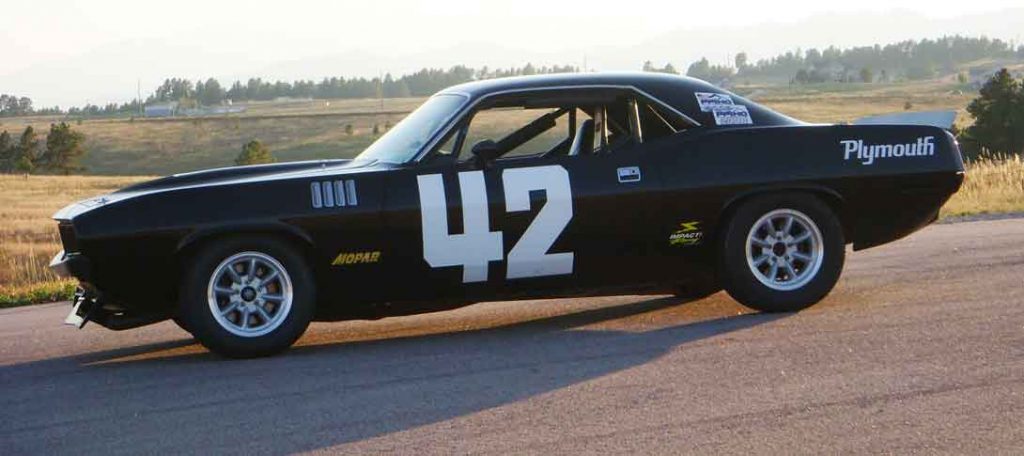

Jess Neal ready to rock ‘n’ roll. (Photo: Artemis Images)

It’s a race where your name goes into the record books regardless of whether you win, come in last or roll off the mountain and vanish. The names of everyone starting in the 87 races held here since 1916 include Mario Andretti and the Unsers–good company, to be sure. This is the granddaddy of all hill climbs. This is Pikes Peak, otherwise known as “The Race To The Clouds.”

Starting area is packed with spectators. Jess doesn’t bother to wave as he woods it in Second and slams Third. (Photo: Artemis Images)

Anyone can drive the public road, with its posted 10 MPH corners, to the summit. But to race, you need to be invited by the Pikes Peak International Hill Climb folks. You’ll also need is a license from a recognized race sanctioning body such as SCCA, and the required safety equipment: fire-resistant shoes, and socks, a minimum 2-layer fire suit, gloves head sock, minimum SA 2005 or newer helmet and a head and neck restraint system. Classes range from motorcycles to tandem-axle semis.

The fast class fields purpose-built million-dollar cars that pound out 1000 horsepower. The quickest time on the mountain to date—a 10.01.408 achieved by Nobuhiro Tajima in a Suzuki XL7 in 2007 is about half that of the first winner–Rea Lentz in a Romano Demon Special.

Dirt sections can be like driving on greased ball bearings. Rocks chew up tires big time. (Photo: Artemis images)

This is Jess’ second hill climb. He’s usually road races with his Rocky Mountain Vintage Racing compadres. Last year Jess looped it in the dirt. He hopes to do better on his birthday.

Jess picked up his ‘Cuda back in 1999 from an add in Grassroots Motorsports magazine. This was before ‘Cuda prices went though the roof. The car came from New Hampshire, which is the reason for the New England accent MOPAH license plate.

Set up for road racing by the previous owner, the ‘Cuda was kinda nasty with fiberglass fenders and doors, IMSA-style ground effects, and old paintjob that was spider-webbed everywhere. But it had a really neat engine—a Joey Arrington (X-block) with a lightweight billet, knife-edged crank, Carillo rods, 13-to-1 Wiseco slugs, Dick Landy-prepped W5 heads—all the trick stuff. The previous owner had driven the ‘Cuda to class championships, two years in a row. Amazingly, the car came with its original build sheet. While the fender tag was gone, the VIN still was there, and Jess was able to match the sheet to the numbers on cowl and trunk stampings.

Front spoiler is made from original molds which George Barris fab’d for Dan Gurney. Sharp-eyed readers will notice the spoiler is attached to a ’70, ’72-’74 front valance because it will not fit the ’71 which has turn signals. Front fenders are much cheaper ’72-‘744 versions that have been widened and have lightweight ’71 gill decals. Hood is factory ’70 AAR

Paint is by Bob Hill in Colorado Springs

.

According to the sheet, the car was a ’71 ‘Cuda (BS23) model that was a 3-speed console car. When Jess bought it, the ‘Cuda still retained its original door panels, and woodgrained trim. Options on the build sheet included leather interior, rim-blow wheel and Light Group.

Gee, wonder how quick this thing is? Let’s find out at Bandimere Speedway’s quarter mile. The road race ‘Cuda did not care much for drag racing and it let Jess know in not-so-subtle terms by blowing the engine big-time. It blew so hard, that a piece of camshaft came out through the intake. Everything inside broke—except the rods. All that was salvageable was one head, the distributor and the oil pan.

‘Cuda wears its original valance, hill climb-mutilated rear tires, fiberglass mono leaf spring mounts, fiberglass rear bumper and shortened exhaust which originally exited in front of the rear tires and was hammered shut by stones flying off the front tires.. Aluminum rear spoiler is attached to fiberglass trunk lid which is pinned. Trunk contains 8-gallon fuel cell in a steel container. All Pikes Peak Hill Climb cars have a “tail-waggin’ good time” going up the mountain.

Jess’ new bullet, a 582 HP (at 6000 feet) 416 stroker machined by McCabe Motorsports, and assembled by Jess, has a 10-to-1 squeeze, Crane roller cam, an old Fuel Curve Engineering carb that’s fitted with a 750 base plate, a 650 main body, and with the rear metering block’s tubes brazed. The carb seals to an original ’70 AAR hood. Custom headers were designed to clear the rack and pinion, as was the Canton oil pan that sports the trick trap door box around the pickup for road course racing, and a welded-on crank scraper.

Moving through the driveline, Jess went with a billet steel flywheel and Centerforce clutch. He built the close-ratio trans himself, replacing the cracked original Direct Connection main case with Passon aluminum main and tailshaft housings. A Mark Williams driveshaft spins and 8-3/4” rear packed with 4.30 cogs and a Detroilt TrueTrac. Mark Williams did all the gear setup work.

The rear axle has Wilwood disc brakes and quad shocks with the extra shocks installed parallel to the fiberglass mono leafs for rear housing control. The front suspension is basically stock with oversize torsion bars, Carrera shocks and JFZ brakes.

Wheels are 15×8 MiniLite copies with BFG radial street tires 245 in front 255 in rear. Rear tires are good for only one event due to severe chunking out of the tread on the dirt sections of the course. The ‘Cuda weighs 2800 lbs. without the driver.

Pikes Peak’s dirt sections are brutal on tires. Rhys Millen came across the finish line on race day with only the tire beads still on the wheels. Jess’ choice of old BFG Radial T/As on 15×8 Superlite wheels is an attempt to make the ride look like something Dan Gurney would have campaigned back in 1971 if he had run.

Inside is bare bones with a full rollcage, Kirkey welded aluminum driver’s race seat and a fiberglass “scare”seat. Added gauges keep tabs on the high-winding smallblock.

Interior of door shows no door beams which originally were two pieces of .125″ thick x 10″ tall corrugated steel sandwiched together, meaning tons of weight removed. All window-related items are removed. Over 80 holes were punched in the inner and lower panels, with the edges rolled to retain panel stiffness and allow the use of original handles. Doors now weigh roughly 34 lbs. or double that of fiberglass

Jess gets to the starting line around 9 a.m. He’s come from the driver’s meeting where he’s hob-nobbed with the world champion rally guys who’ve come from Sweden, and racing celebrity Max Papis, who has shoe’d everything including NASCAR, Indy, GTP—you name it. Max opens the event by driving a “pace lap” up the mountain in a Porsche.

The starting line is a zoo with spectators milling around, asking questions about the cars, racers trying to make their way to their position in line, and general tumult. The vintage class, consisting of 10 entries, will be the first class up the mountain. Jess has qualified 5th and edges into position. He carries 8 gallons of fuel, and he’ll burn probably half that.

Factory gauges still are in place behind Afco switch panel. Added are racing tach and oil pressure gauge. Oil and water temp gauges reside in original ash tray location. Hurst Super shifter with Reverse lockout controls close-ratio 833 which is housed in Passon aluminum main case and tail shaft housing. Note factory original 3-speed shifter boot. MSD control unit is mounted to front console bracket. Original dash pad is uncracked and original speaker grill is unwarped. Steering column is custom with quick-release wheel and 2:1 Howe quickener (a small gearbox) mounts between the wheel and Chrysler rack and pinion. Race seats and 5-point harnesses secure passengers. Upside-down mustard jar in the rear acts as an overflow bottle for the diff fluid.

The cars are flagged off at 2-minute intervals. The car in front leaves. Jess goes into an adrenalin-fueled state of concentration. There are butterflies in his stomach. The flag comes down. Jess likes to leave in “spectacular” fashion, engaging the clutch at 5 grand and spraying onlookers with debris kicked up by his tires. He grabs Second at 7 grand and steers into the left-hander. Once through that, he hits the timing strip that starts the clocks. Into Third now for the gentle right-hander and slamming into Fourth down a short straight followed by a double-apex right-hander then a double-apex left.

Aluminum skid plate protects the Canton Systems road race oil pan which is modified to clear the rack and pinion. ’70 valance with AAR

race-style spoiler mounts scoops to direct cooling air to front brakes for paved road course events. Grille is a mucho broken and repaired original. Note wrong size head light buckets in fenders. Front bumper is a fiberglass replica. All-important Mopar Action decals provide a winning edge.

Ducts from scoops deliver air to the center of the rotors. Front sway bar is removed and the front is raised one inch for hill climb duty. Steering is Chrysler rack and pinion with heim joints in place of outer tie rods. Owner-fabbed massive front bumper brackets are made from .125”x1.125” aluminum supporting fiberglass bumper.

The first bad turn is Engineer’s Corner. One of the Swedish world rally drivers came into Engineer’s much too hot in practice, and slid off the course down a 6-ft. embankment. So much for overconfidence. After Engineer’s, the rest of the paved section is really fast—4th gear on wood. Jess is clocked at close to 90 MPH in this stretch. The fun comes to an end (or starts, depending how you look at it) as the road transitions to dirt and a chicane. Real racers just tap the brakes and drift right through. Jess isn’t as brave and hits the binders before the dirt, drops into Second and accelerates. The rack and pinion has a limited turning range, unlike some cars here that can turn their front wheels almost sideways. So Jess has to be careful how far the rear comes out.

Mild 340-based stroker, now 416 cubes, runs 10-1 compression and .600”-lift cam. Horsepower is 582 at 6000 feet altitude. Up top are Dick Landy-prepped W-5 heads and intake. Carb is an antique Fuel Curve Engineering Holley. MSD distributor handles the sparks. Remote oil filter system is installed. Previous owner swapped a fuit can for the wiper motor (to save weight? “Cause he had nothing better to do?) Jess will put a Libby’s label on it. The battery is relocated to the trunk. Aluminum Griffin

radiator handles cooling. Rollcage is tied to the front shock towers which are tied to each other. Hood is sealed to the carb and held by four pins

The course switches back to pavement and then back to dirt on the final leg to the summit. There’s no spinning out like last year, and Jess hits the finish and places 3rd in his class, posing a time of 14.43, with an average speed of about 50 MPH. It’s the best birthday present he can possibly imagine. In “The Race To The Clouds,” Jess is on Cloud Nine. And his name is in the record books.

SETTING IT UP

Setting up Jess Neal’s road race ‘Cuda for hill climb competition took a little more than adjusting the rear-view mirrors. One of the challenges on Pikes Peak is the weather. If it rains, hails or in the case of 2009, snows, the road is totally different than if it is sun baked. When dry, the paved sections have grip and the dirt doesn’t. Add moisture and the opposite is the case. Moisture on the dirt part of the road is your friend but only until it starts to get muddy. If it’s sun baked, the road is like driving on greased marbles because the dirt is packed and has a hard surface that has pea gravel on top. Moisture softens that hard surface and allows the tires to break through.

Changes to the car start with raising it—for two reasons. First, the dirt sections can have ruts formed when the rain water runs off the mountain. Two, some vehicles will pull rocks up on the “line” by hanging a front tire over the edge for side bite. Normally, the bigger rocks get pushed to the edges of the road but now they are just waiting for your oil pan, steering linkage or exhaust system. Having some ground clearance will help prevent bottoming out the car and reduce the chances of under-car damage.

Remove all swaybars allowing the suspension to move more freely. Since the car doesn’t roll nearly as much while cornering on dirt the bars are just added weight and stiffness.

Reduce spring rates. Again, this helps loosen the suspension and keeps the tires in contact with the dirt. The “less is more” principle applies here. Road-race alignment settings are not changed.

Rear gears are switched from a 3.9 gear to a 4.3 to make up for lost power at altitude. This helps launch the car off the paved switchbacks.

Tires are BFG T/A radial street tires with circumferential and diagonal grooves which helps clear small gravel and get the tread blocks onto hard surface. After 3 days of practice and the race day run, the rear tires look like an ear of corn that’s been gnawed on by a semi-toothless hillbilly.

Seal the radiator to the front of the car to force as much air as possible through the radiator. There is a lot less air present at this altitude to cool things down.

Engine is tuned for an altitude of around 12,000 ft. which makes it a little lean at the start of the race and a little rich at the end. Tune it for higher elevation and you give up power at low altitude and risk putting too much heat in the engine. Another problem with too lean can be ruining the power valve with a lean backfire through the carb which will instantly dump too much fuel for the engine to handle and end your day. Tune the carb for lower elevation and you lose more power at high altitude, use more fuel, risk washing down the cylinders, fouling plugs and make the car sluggish coming out of corners.

Jess is supposed to be running the car according to General Competition Rules for the ‘70-’71 Trans Am season. Obviously, he’s way illegal–especially under the hood.