‘Cuda Creation

Reflections on designing the A-body Barracudas

The stories are the neat part. Personal recollections and insights of folks on the front lines of Chrysler racing, engineering and designing back in the day.

Take the 1964-’69 Plymouth Barracudas, for example. Talk to the stylists, and you get some insight into the car’s creation, that you would miss by looking just at the big picture. With that in mind, we dialed up John Samsen, one of the stylists in the Plymouth design studio, when the A-body Barracuda began to take shape back in 1962. John told us that, unlike the usual process of a car idea first being conceived by sales or product planning, and then handed off to styling to develop it, the ’64 ‘Cuda began in the design studio and was later accepted by Chrysler management. Irv Ritchie, one of the designers, had always like fastback cars, especially the GM Olds, Buicks and Caddys of the late ‘40s. Fastbacks became passé when hardtop convertibles came along, and hadn’t been produced for a decade when Irv came up with the idea of grafting a fastback roof onto a Valiant, to make a sporty car. When hardtop convertibles arrived on the scene, they took the market away from fastback models, and they had not been produced for about a decade.

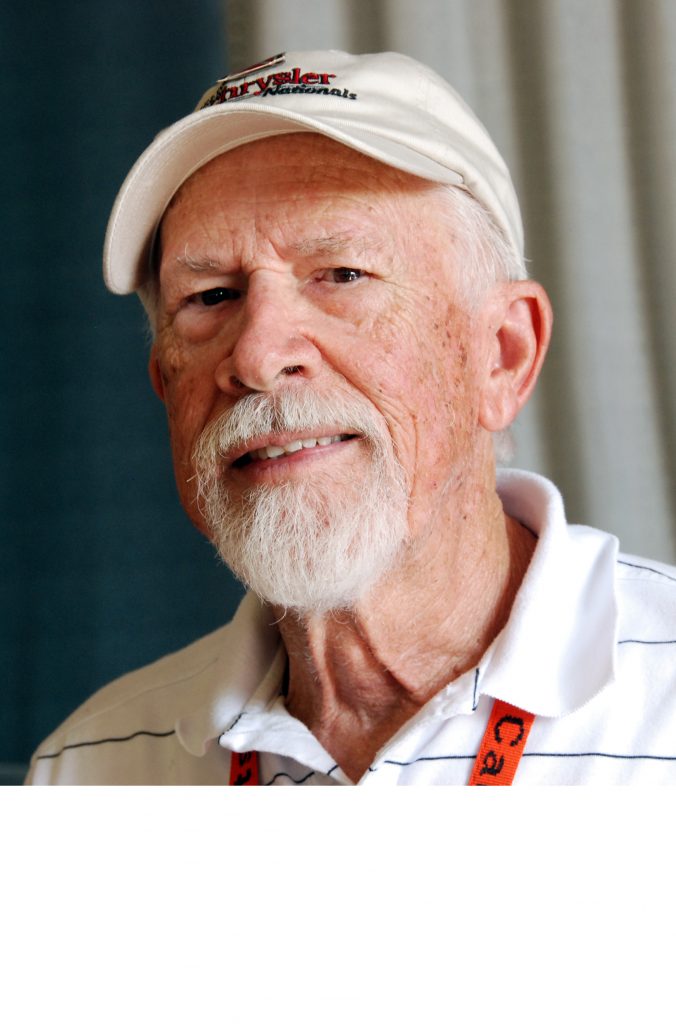

After penning some concept sketches, Irv made scale layouts with a Valiant package, and saw that the concept was viable. The studio management liked the idea and so they had him make a full-size layout and rendering. When Plymouth execs saw the rendering, they became real excited, and authorized a full-size clay model study project. Unbeknownst to Plymouth, this idea for a low-priced 4-passenger sporty car occurred around the same time that Lee Iacocca came up with his idea for the Mustang. When the Plymouth designers submitted their sketches for roof and rear of the new car, John Samsen’s concept was given the nod, and he was assigned to direct the modeling of those sections. John had a liking for reverse C-pillars and large backlights. Elwood Engle, in charge of all Chrysler styling (he came on board after Virgil Exner was taken out), would drop by occasionally to see how things were progressing, but he made few suggestions.

‘Course the challenge in any styling/design department, is to take individual contributions from the various team members who worked on different areas of the car, and make it appear as if the final design was created by a single person

As the model progressed, experts from Pittsburgh Plate

Glass (PPG) were called in to see if they could make the large backlight, as

nothing like this had ever been done before. The design studio made plaster

molds of the backlight for them, which they used for development. The

production backlight for the ’64 ‘Cuda was not what Samsen had originally

designed, as PPG was unable to hold the shape ordered by the design studio. The

compromised glass shape bothered Samsen, but, it seems, no one else.

Something else bothered Samsen, and all the other designers that had worked on the project—the name that Plymouth marketing came up with for the car—Panda. Panda? Are you kidding? OK, marketing told the sketchmen, you come up with a name. The designers each made their own list of names, and one from Samsen’s list—Barracuda—was chosen. According to Samsen, one engineering VP didn’t like the ‘Cuda and tried, unsuccessfully, to derail its production. When the car hit the showrooms and was reasonably well received, this guy was quoted in newspaper articles claiming credit for the ‘Cuda’s design.

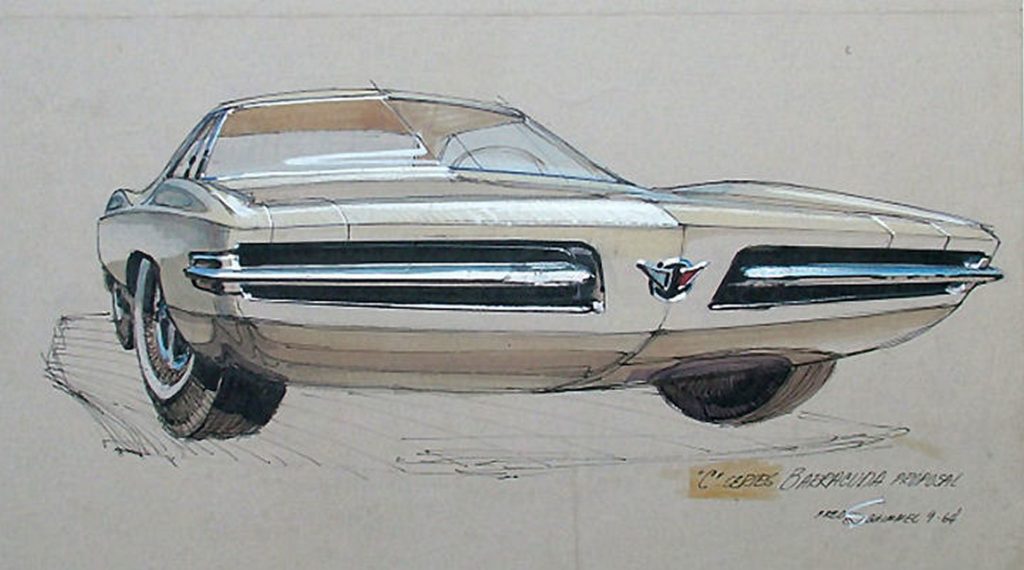

As an interesting side note, when John Herlitz joined the Plymouth design team in ’64, he had just come from GM, where he had seen the creation of Pontiac’s GTO. Chrysler was looking to create a show car based on the ’64 Barracuda to generate some buzz for their new A-body. Herlitz was given the show car assignment, and his concept ended up being pretty close to the GTO. Chrysler built the car, and called it the Barracuda SX. According to Samsen, the show car made its debut in ’66 as a ’67 model, and GM raised a big stink about it, because of its similarity to their Goat. Chrysler caved, pulled the car off the circuit, and never released any additional photos of the car. As a result, hardly anyone knew about it. But, when the designers were working on the ’67 A-body, the directive was that the production ’67 Barracuda car resemble the Barracuda SX show car as much as possible. Herlitz was an obvious choice to be a lead designer on the project, but he was called up for National Guard duty. So the job of supervising the clay modeling fell to John Samsen and Milt Antonick. Samisen did the grille, front end and the hood, while Antonick did a lot of work on the body sides. Other designers, such as Dave Cummins and Fred Schimmel also contributed.

Another one of Samsen’s contributions to the Barracuda was the chrome band between the decklid and the backlight. The engineers said the decklid required external hinges, as there was no room in the tiny trunk area for conventional goose-neck hinges. The chrome band was a very successful in disguising those otherwise unattractive external hinges.

The ’67 grille is a story in itself. The engineers had moved the front frame rails apart to permit big-block engines, which would require larger radiators for cooling. They were concerned about airflow through the grille. Samsen, in creating the grille, had to come up with a low restriction design. He leaned his head back on his chair, and looked up at the ceiling, waiting for inspiration. It was then that he noticed the egg crate grilles in the studio ceiling lights. They were real thin and made of aluminum. Hmmm…

Samsen obtained a chunk of light fixture grille from the manufacturer, and cut it to fit. It was perfect. The grille then had to be proven by engineering to make sure it would hold up under the rigors of real world driving conditions. It passed with flying colors. With the exception of a “peaked” hood introduced in 1969 (which some thought spoiled the car’s Euro flavor, and which reappeared on ‘73-‘76 Darts), the second-gen, ‘67-‘69 ‘Cudas were all virtually identical.

While all the ‘64-‘69 Barracudas were based on the

rock-sold Valiant A-body platform, they never matched the supposedly all-new,

really Ford Falcon-based, Mustang in sales. But, for once, Chrysler’s timing

for a sporty car was right, and the first generation Barracudas pulled more

than their share in contributing to Ma Mopar’s bottom line.